Building Myanmar Climate Strategy Through Protecting Indigenous Land

Author: Naw Eh Htee Wah

KEY MESSAGE

- The political connection between land and climate change is shown by the way that land management practices in Myanmar have a major effect on emission reductions and climate resilience.

- Legal reforms are required to address policy gaps that threaten both indigenous people, local community and climate ambitions.

- To ensure sustainability and equity in climate resilience and emissions reduction, Myanmar need to prioritize recognizing and including indigenous communities in land-related policies which addressing current legal frameworks that often neglect indigenous land rights and result in displacement and marginalization.

Introduction

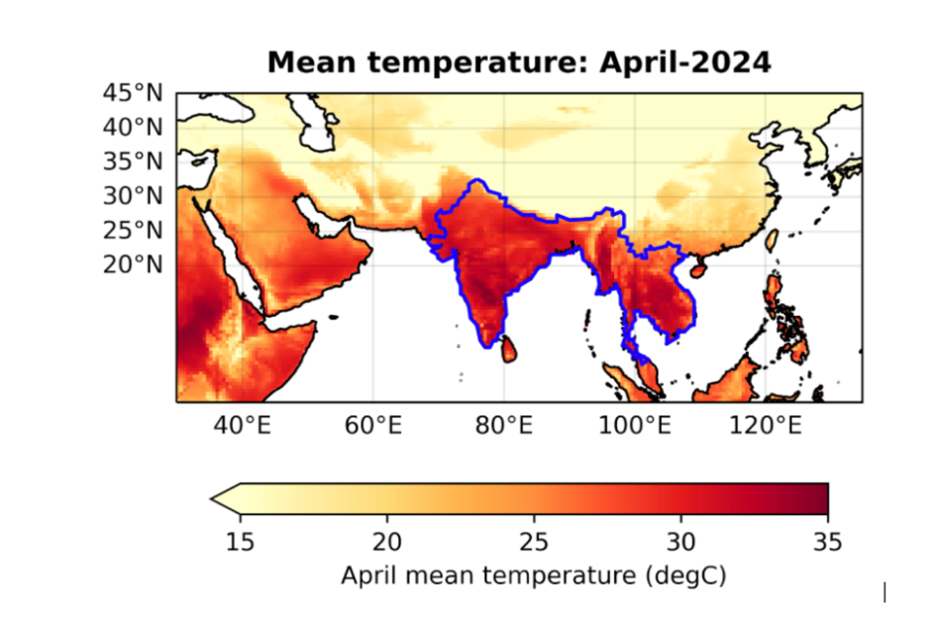

The very recent natural disasters were Cyclone Mocha which happened on May 14, 2023, especially to Rakhine, Chin, Kachin, Sagaing, and Magwe, affecting 1.5 million people and causing over 455 deaths. In addition, El Nino (extreme heatwave) occur currently in summer with temperatures reaching 47.1 degrees Celsius (Voice, 2024). Based on the national news, in July, 2024, upper part of Myanmar Kachin State significantly flooding. These natural disasters prove the increasing climate-related challenges worsened by ongoing climate and environmental degradation. Climate change’s effect on land and terrestrial ecosystems, according to information in the IPCC’s 2019 Special Report on Climate Change and Land which creates serious risks to human populations and ecosystems around the world.

Among these countries, Myanmar is the second most vulnerable to climate change, as evidenced by 2021 Global Climate Risk Index. In response to the impacts of climate change, Myanmar has made international commitments under the Paris Agreement to tackle climate change through its nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and others related laws and strategies, which includes top-down conservation system and the approval of commercial and industrial plantations within Permanent Forest Estate (PFE) areas under forest law, has affected indigenous and local communities who are in ancestral domain. These actions have led to circumstances of climate injustice. Therefore, local communities’ ability to sort out the climate change problem are obstructed by agricultural land disputes, decades of authoritarian rule and armed conflicts. Moreover, the continuing impacts of climate change occurs due to the military-linked forces and unethical business behaviours.

Myanmar’s commitment to global climate policy includes signing the Paris Agreement in 2015 and pledging to combat climate change through its nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The country aims to reach 30% of its land as Permanent Forest Estates and 10% as protected areas by 2030. However, these initiatives often proceed without Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from affected communities, leading to human rights violations and displacement (CAT, 2018). Therefore, it has become a kind of green grab, allocating land and resources in the name of environmental conservation. Moreover, global natural conservation, state authority and control expand into a political forest under the control of insurgents as a counter-insurgency strategy (Woods, 2019).

Indigenous peoples, who protect approximately 80% of the planet’s biodiversity (Fleck, 2022), suffer from global warming, deforestation, and pollution, threatening their survival and traditional knowledge (Anderson, 2023). Secure land tenure rights are crucial for their well-being, resilience, and sustainable practices (Correa and Jansen, 2022).

Land and climate change are politically linked because land management practices have a significant impact on emissions reduction and climate resilience. In order to address deforestation and forest degradation, Myanmar implemented a number of environmental and forest policies between 2011 and 2021 as part of the country’s democratic transition. However, these policies often ignored the rights and recognition of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs). This paper explores the need for legal reforms by observing the policy gaps in Myanmar’s legal system that threaten indigenous rights and climate goals.

In that context, it is important to understand the landscape of forest conservation and land tenure in Myanmar such as the challenges that indigenous communities face regarding their land and cultural practices within the framework of Myanmar climate change strategy , the influence of Indigenous leaders in Myanmar on climate change mitigation strategies through both policies and collective action and how future federal democratic government of Myanmar can recognize their ancestral territories in accordance with international standards. Generally, there is a critical need to recognize and respect Indigenous self-determination, Indigenous knowledge and practices, land tenure rights, ecological rights and Indigenous people rights. To achieve this, the adaptation and formulation of new polices and frameworks are necessary to protect indigenous land while proceeding Myanmar climate strategy and mitigating climate change.

Figure 1 – flooding in Northern Part of Myanmar

Source: Kachin News Group

Figure 2 – April mean temperature 2024.

Source: World Weather Attribution

(Note: The blue outline shows the region with the most extreme heat in South Asia)

Who are Indigenous People in Myanmar?

Myanmar is an ethnically and ecologically diverse country with a great diversity of indigenous peoples. Indigenous is a contested concept in Myanmar, with different definitions held by different communities. In Myanmar language, for example, the term ‘taingyinthar’, literally translated as sons of the nation, is commonly used to refer to indigenous or ethnic peoples (Khant, 2024). In Karen language however, the term ‘pwa thoo lay poe’ is used to refer to indigenous peoples, translated as peoples who have lived in the same place since time immemorial. This term reflects the relationships that people have with land, biodiversity and resources, and is not, like the term taingyinthar linked to ethnicity. According to this definition, anyone with ancestral links and relations with a particular place could be considered to be indigenous.

The All-Burma Indigenous Peoples Alliance, a network of over 30 indigenous organizations and communities across Myanmar concurs with a definition of indigenous peoples as a group of people with historic relations to a territory. In their 2022 policy they define Indigenous people as a group of people identified by self- ascription and ascription by others, who have continuously lived as an organized community on communally bounded and defined territory, and who have, under claims of tenure since time immemorial, occupied, possessed and utilized such ancestral territories, sharing common bonds of language, customs, traditions and other distinctive cultural traits, or those who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural, spiritual and political institutions, but who may have been displaced from their ancestral domains or who may have resettled outside their ancestral domains. The indigenous peoples are rooted and connected with their ancestral territories, and use their territories sustainably, balancing between human utilization and protection of all the resources. (ABIPA, 2024)

Understanding the transformation of Indigenous Land-related policies under climate change strategy in Myanmar

Myanmar aims to reach 40% of its Permanent Forest Estate as reserved and protected area by 2030 which potentially displacing indigenous peoples who lack legal recognition of their ancestral lands. The Vacant, Fallow, and Virgin Lands Management Law, intended to promote investment which often results in land grabbing and displacement of smallholder farmers. The majority of the remaining forested areas are located in Indigenous territories, Ethnic arm control areas, and conflict-affected regions. In order to align with Myanmar Climate Strategies and international commitments, the establishment of PAs is recommended to achieve conservation goals and safeguard crucial biodiversity hotspots.

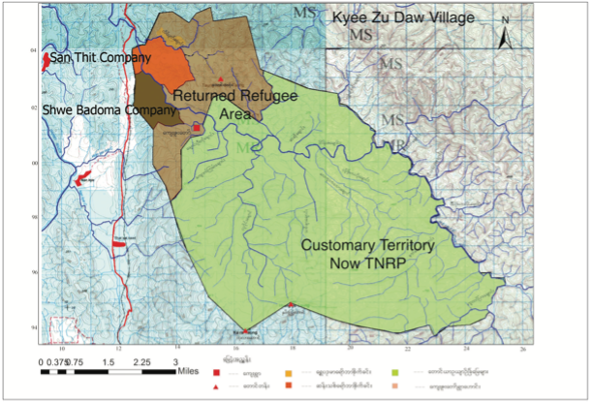

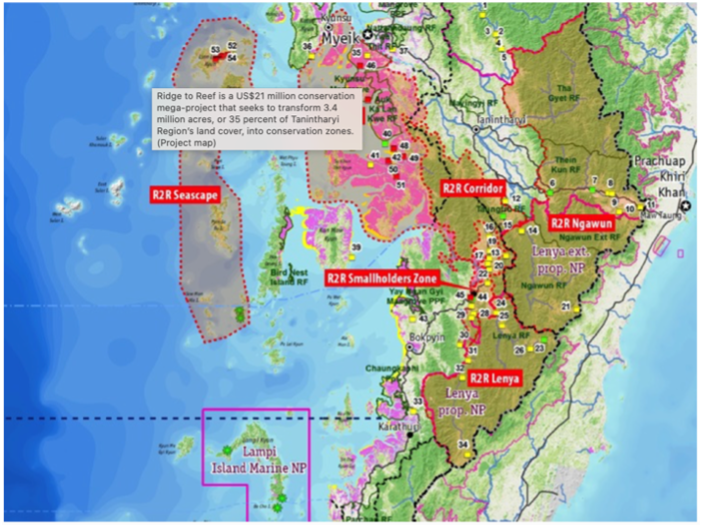

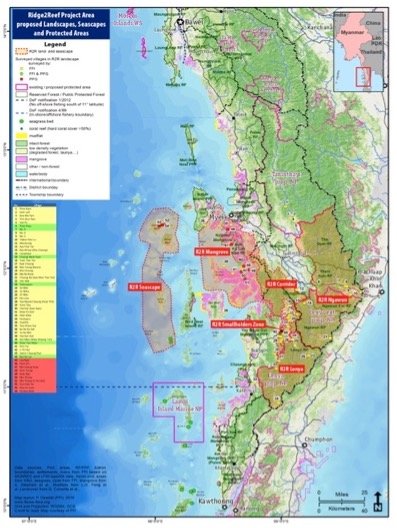

The 420,000 acres of Tanintharyi Natural Reserve Project is located in Dawei Township, Tanintharyi Region was established during civil war displacement, further marginalized local communities (Tanintharyi Friends, 2018). Due to current Myanmar political situation, kind of this situation persists across the country amidst civil war and political instability, leaving Indigenous and local communities living in fear and vulnerability, unable to speak out. The Ridge to Reef project, covering 1.4 million hectares of land, national parks, low land evergreen rainforests, mangroves in the Myeik archipelago, and islands and marine systems which are important resources for Indigenous and local communities in Tanintharyi Region, southern part of Myanmar which threatening Indigenous livelihoods, violating ceasefire agreements at that time, and disregarding community-driven conservation initiatives (Nagar, 2019). The complex situation as top-down conservation efforts, legal oppression, armed conflict, and political instability are all interconnected. Although the government’s conservation policies aim to protect biodiversity, they frequently neglect Indigenous and local communities’ (IPLC) rights which occur in tension and displacement.

Although Myanmar supports international declaration upholding indigenous rights as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity which is committing to protect indigenous knowledge for environmental conservation. UNDRIP grants Indigenous peoples rights to their lands and resources, requiring states to recognize and protect these rights and to obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) before approving projects affecting their lands. Despite these international commitments, Myanmar’s national policies inadequately protect Indigenous rights, failing to establish a legal framework or effective implementation. However, these legal gaps hinder the achievement of climate objectives and the safeguarding indigenous land and forest tenure.

Figure 3: Land use Land use map of Kye Zu Daw village

Source: Taninthary Friends

Figure 4: Ridge to Reef is a US$21 million conservation mega-project that seeks to transform 3.4 million acres, or 35 percent of Tanintharyi Region’s land cover, into conservation zone. (Project map)

The Karen People’s Approach to Climate Justice and Sustainable Landscape Management

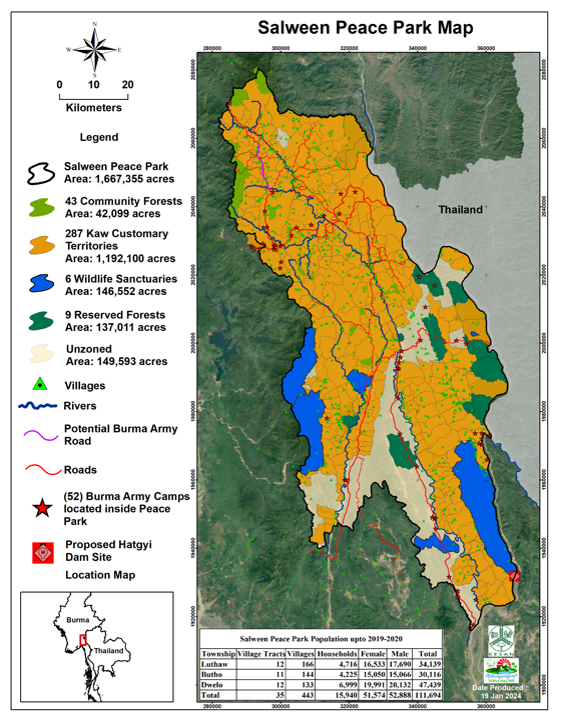

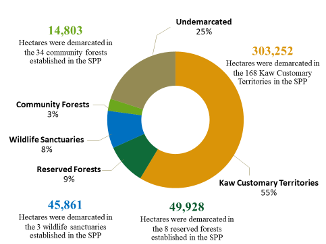

Myanmar Karen Indigenous People have initiated an alternative approach to achieve climate justice by implementing Indigenous-led conservation practices. These practices serve as an example of landscape conservation. It is interconnected territories which managed and govern by locally. This system supports sustainable livelihoods and safeguard watershed areas, waterbodies, mangrove forests, and wildlife habitats across territories. The Salween Peace Park in northern Karen State stands out as a prominent type of indigenous landscape conservation. Covering 1.35 million acres of globally significant rainforest and the territories of 149 indigenous communities, this park is governed by customary law, a community-developed charter, and locally based democratic institutions. In the classification of land use within their jurisdiction, 71.5% is as Kaw customary territories, 2.5% as community forest, 8% as reserved forest, 11% as wildlife sanctuary and 7% as undermarketed area.

Figure 5: Salween Peace Park Map

Source: KESAN

The Salween Peace Park embodies the aspirations of the Karen people for peace and self-determination, environmental integrity, and cultural preservation, highlighting the harmonious relationship between people and nature (KESAN, 2016). Salween Peace Park was formally launched in 2018 and was awarded the Equator Prize in 2020 (Equator Initiative and UNDP, 2020). Moreover, another example is Thawthi Taw-Oo Indigenous Park (UNESCO, 2023). It encompasses 5754 square kilometers of land and is home to more than 70,000 people and a numerous of flora and fauna. Even under the military coup, they are working on draft charter of Tha Thi Taw Oo Indigenous Park, conducted consultation, demarcate and revitalize their ancestral territory. Despite armed conflict and natural resource exploitation, communities form Thawthi Taw- Oo Indigenous Park, SPP and Tanawthri Land Scape of Life are continuing working on innovative nature and rights-based solution for tackling biodiversity loss and climate change. The Karen People have a land and forest policy (Adminkhem, 2016). Their land and forest policies are based on the Karen People’s desire to protect and recognize indigenous land, forest, biodiversity and territory. They understand the importance of recognizing and protecting indigenous communities’ rights to manage their own lands sustainably. Their polices reflect this principle, ensuring that indigenous voices are heard and respected in decision about land use and resource management. Without support and recognition from Myanmar government, the Karen Indigenous people taking matters into their own hands. The Karen Indigenous People’s implementation of Indigenous-led conservation practices and Indigenous Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) in Myanmar demonstrates how climate justice can be achieved through local stewardship of ecosystems.

Indigenous initiative new policies development in Myanmar

Due to the challenges that Myanmar Indigenous and local community face climate change mitigation strategy under some of Myanmar existing laws and framework, Myanmar Indigenous people came together since before 2018. This Indigenous movement platform call “All Burma Indigenous People Alliance”. Those Indigenous representatives from across Myanmar collaborated and formed the alliance of All-Burma Indigenous People’s Alliance (ABIPA). ABIPA’s member groups consist of indigenous peoples, community-based organizations and ethnic civil society organizations from all over Myanmar, that are involved in the protection and empowerment of indigenous cultures, traditional knowledge, livelihoods, land rights, indigenous rights, environmental protection and climate change mitigation. The 30 member groups are from Tanintharyi Region, Bago Region, Nagaland (Sagaing), Karen State, Shan State, Chin State, Kachin State, Mon and Karenni (Kayar) have joined the platform. ABIPA member groups believe that the new generations will be able to continue preserving biodiversity, forest and environment in Myanmar through the practice and recognition of indigenous territories, indigenous knowledge and customary governance systems.

In order to achieve recognition and establish a legal framework within policy, the indigenous alliance has proactively taken steps without waiting for government intervention, which they believe would be indefinitely delayed in Myanmar as there is no legitimate government. Consequently, in 2024, this alliance formulated and issued both a declaration and policy. The declaration formulates the right to self-determination for indigenous peoples, while the policy outlines the rights to territorial governance for those indigenous and communities (ABIPA, 2014). In addition, Karen Indigenous people have developed Kawthoolie Climate Action to tackle climate change issues and mitigation. These documents assert Indigenous communities’ authority over their territories which promoting sustainable land management, preventing deforestation, conserving biodiversity, and enhancing climate resilience. It aligns with international frameworks such as the United Nations Framework Conservation on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD) (CBD, 2023). Through their initiatives, Indigenous communities can link up to the UNFCCC and UNCBD through non state actor platform. Non-state actors play important role in linking local actions to the broader objectives of the UNFCCC and UNCBD. These efforts can reduce of land conflict, ensure smoother implementation of conservation strategies and incorporate indigenous knowledge into national climate policies.

Conclusion and Recommendations

These suggestions offer a thorough structure for developing Myanmar’s climate strategy, with a focus on safeguarding indigenous lands and communities in accordance with global norms and indigenous rights and self-determination principles. Adhering to these recommendations is crucial for the future of Myanmar Federal Democratic Government, Indigenous leaders and Ethnic Resistance Organizations (EROs) to incorporate into their national constitution, state constitutions and policies to ensure the protection of Indigenous and local community lands, thereby supporting Myanmar’s climate strategy.

- Myanmar has yet to fully commit to acknowledging the rights of indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands. There is a clear absence of laws and policy initiatives that align with international norms, such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). As a result, the ability of indigenous communities to exercise self-determination and effectively participate in climate mitigation and adaptation strategies is compromised. It is imperative for a future federal democratic government of Myanmar to recognize indigenous peoples and their ancestral territories in accordance with international standards, including the UNDRIP. This recognition should encompass the right to self-determination, ownership, governance, and management over their lands, territories, and resources.

- To grant indigenous communities’ formal recognition and secure tenure over their ancestral lands and territories, it is needed to place ancestral domain at the core of a new constitution from national level and state level for a Federal Democratic Myanmar. This must acknowledge the importance of land to local and indigenous communities by affirming their ultimate ownership of land and resources, while also respecting the authority of Federal States and Authorities to establish local land regulations in line with local governance systems.

- In developing new constitutions and other related framework, it is imperative to include indigenous representatives who can provide valuable inputs and share insights grounded in local contexts. These recommendations should be integrated into the policy making process to ensure that the resulting policies are culturally informed, contextually relevant and effectively address the needs and gaps within Indigenous communities to protect their land under climate change strategy and climate mitigation.

- In building Myanmar’s climate strategy through the protection of Indigenous land, Indigenous leaders should continue to take initiative in facilitating the development of new policies and frameworks which ensuring the inclusion of other experts and representatives in the process to comprehensively address existing needs and gaps. Then, it can link up to UNFCCC and CBD’s Subnational and local biodiversity strategy and action plan.

References

[1] ABIPA. Declaration and Policy. 2024, www.abipa.indigenousburma.org/research-report-briefing/. Accessed 21 June 2024.

[2] Adminkhem. “KNU Issues New Land Policy.” TBC | Theborderconsortium |, www.theborderconsortium.org/reports-survey/knu-issues-new-land-policy/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

[3] Adminkhem. “KNU Issues New Land Policy.” TBC | Theborderconsortium |, www.theborderconsortium.org/reports-survey/knu-issues-new-land-policy/. Accessed 17 May 2024.

[4] Anirudha Nagar. “Myanmar: Ridge to Reef Conservation Project | Accountability Counsel.

[5] Conservation Alliance of Tanawthari. (2018). Our Forest Our Life. ICCA Consortium.

[6] Fabiano de Andrade Correa, and Louisa J.M. Jansen. CLIMATE CHANGE and TENURE RIGHTS Interlinked Challenges in Myanmar Policy Brief. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2022.

[7] Kara Anderson. “Indigenous Communities and Climate Change.” Greenly. earth, 2023, greenly. earth/en-gb/blog/ecology-news/indigenous-communities-and-climate-change

[8] KESAN. (2019). The Salween Peace Park Vision. https://kesan.asia/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/SPP-Briefer-1.pdf

[9] Khant. “The Quest for Recognition: Redefining Indigenous Identity in Myanmar.” Tea Circle, 6 Mar. 2024, teacirclemyanmar.com/politics/the-quest-for-recognition-redefining-indigenous-identity-in-myanmar/.

[10] Progressive Voice. “Double Threats of Climate Change and Military Violence – Progressive Voice Myanmar.” Progressive Voice Myanmar – Amplifying Voices from the Ground, 18 May 2024, progressivevoicemyanmar.org/2024/05/18/double-threats-of-climate-change-and-military-violence/. Accessed 1 July 2024.

[11] Tanintharyi Friends. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: The Struggle of Returning Refugees to Resettle Their Lands in Ye Phyu Township. 2018.

[12] Thawthi Taw-Oo Indigenous Park (TTIP). (2023). Unesco.org. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/thawthi-taw-oo-indigenous-park-ttip.

Download full article >>> Click