Assessing Deliberative Policy Practices in Myanmar: Policy Perspectives Towards Effective and Legitimate Deliberation

Author: Thurein Lwin

Advisor: Piyapong Boossabong

Executive Summary

The research aims to evaluate deliberative policy practices within existing local governance systems, identifying gaps in promoting public participation spaces, and proposing policies to address these gaps for enhancing effective and legitimate deliberation. Myanmar’s bureaucratic culture, characterized by a ‘Do nothing; be uncomplicated; and avoid trouble’ ethos, along with the influence of the Parachute Policy, significantly impact the country’s policymaking environment. Public participation opportunities are more accessible at the local level compared to the state and union levels, yet local governments lack fiscal authority. Case studies of local government bodies, such as Development Affairs Organizations & Committees, demonstrate that increased engagement with the public fosters legitimacy, trust, political stability, and sustainable development. However, centralized training for government officers at the national and state levels, coupled with a lack of deliberative training support for local officers, poses barriers to fostering public engagement. Conflicts in priorities between winning parties and existing bureaucratic structures hinder policy reforms in Myanmar. To address these challenges, there is a need to update laws, regulations, and standard operating procedures to foster coordination between national, state, and local levels, while also establishing learning platforms and cultivating an effective working culture. Policy recommendations include fostering the Ideal Deliberative Policy Forum (IDPF) through a pilot project especially in areas controlled by ethnic armed resistance forces. This initiative, in collaboration with scholars and development agencies, will fill existing gaps and promote the quality of public participation, legitimacy, and effectiveness in local governance in Myanmar.

Problem Statement

The objective of the study is assessing the deliberative policy practices to understand the gaps in existing local governance systems in promoting public participation space. Developing the ideal deliberative policy forum is essential for enhancing effective and legitimate deliberation, thereby promoting the quality of public participation.

It is noteworthy that the people of Myanmar are highly engaged in political activities, make thoughtful political decisions, and actively participate in political reforms with rationality, clarity, and honesty. All political leaders and scholars acknowledge that the people have played a responsible role in navigating the ups and downs and the challenging cycles of Myanmar’s political landscape.

The people have continuously and relentlessly fought across generations for the country’s significant milestones, including the independence in 1948, the end of the Burmese Way to Socialism, and, since 2021, the struggle against military dictatorship and the establishment of a federal democracy. This struggle is likely to continue for many more years.

Figure 1: Political Space and Political Culture Reciprocal Effects

Source: Author simulation (2024)

In Myanmar’s political systems, the role of the people has always been important, but these systems have restricted public participation. The lack of political space for people to be involved in the political system has weakened political culture and had reciprocal effects. The figure 1 illustrates how political culture improves as the political space for people’s participation increases.

In the same way that there were restrictions on the processes by which the people could participate in policymaking, the construction of Myanmar’s government bureaucracy also inherited a colonial legacy, becoming a bureaucratic system lacking accountability and responsibility to the people. This government bureaucracy fosters a ‘Do nothing; be uncomplicated; and avoid trouble’bureaucratic culture and Parachute Policy. In Myanmar, the practice of appointing high-ranking military officers to oversee ministries and other administrative departments from above has completely undermined the government’s administration. This culture refers to a government culture that operates with entrenched traditional practices, rejecting innovation and reform within its bureaucratic framework. This government system limits the political space for public participation in policymaking and prioritizes a culture where only traditional policy analysis (TPA camp) such as government officials, politicians, and experts lead and carry out reforms. As a result, the public feels discouraged from engaging with government departments, believing that their quality of life will not improve and will, in fact, encounter more complicated and delayed systems.

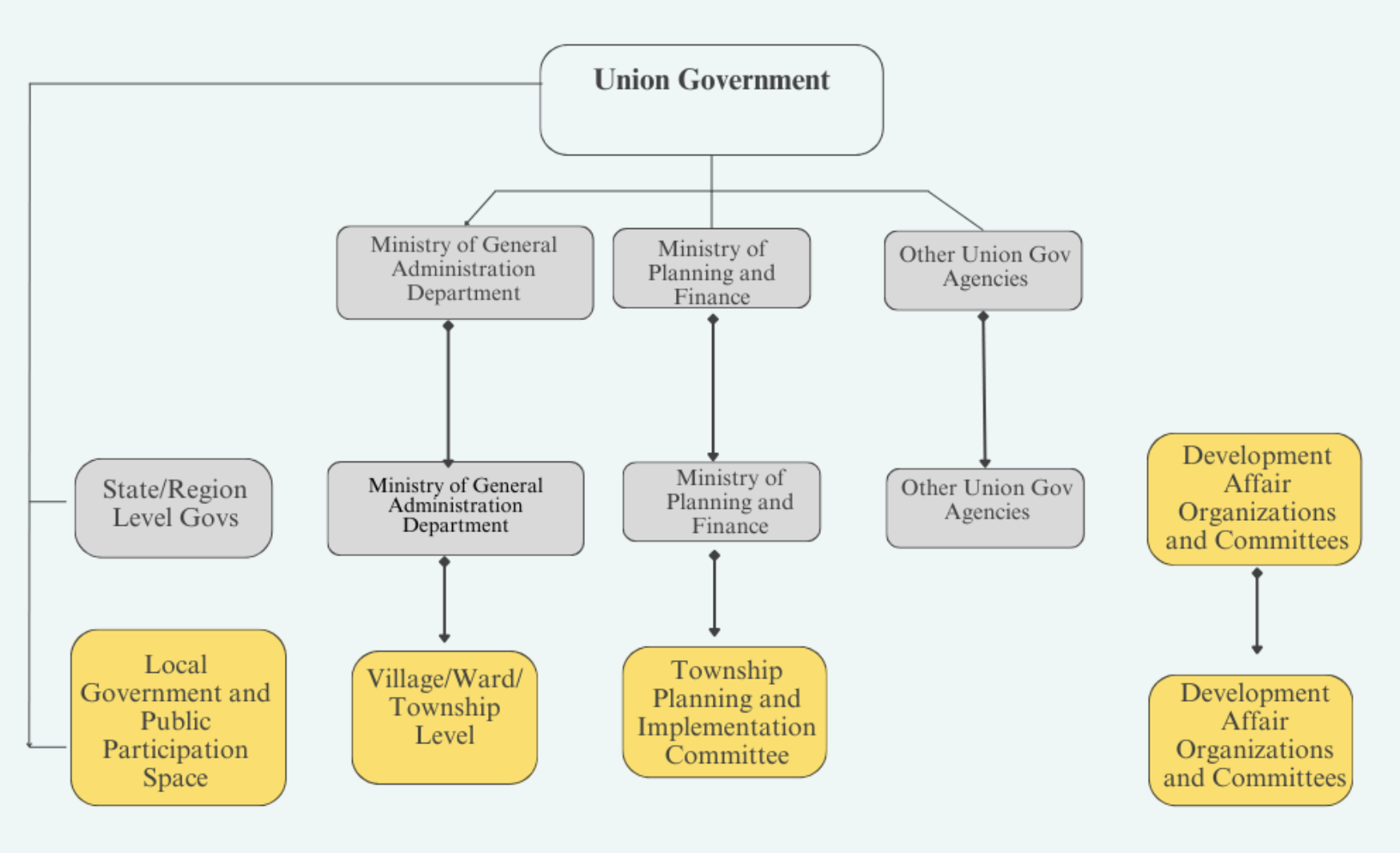

Since the implementation of the 2008 constitution, there has been a limited space for public participation in policymaking channels. However, this has led to the emergence of public participation spaces at the local government level, also known as the third tier of government. Within these local governments, three main departments facilitate public participation in policymaking: (1) General Administration Department (GAD), and (2) Township Planning and Implementation Committee (TPIC) and (3) Development Affairs Committees. Development Affairs Committees and organizations are overseen by state-level governments, while the GAD coordinates government units nationwide under the administration of the union government. TPIC serves as a public platform for collecting annual plans and is managed by the union government.

Figure 2: Different Layer of Government and Public Participation Space

Conceptual Framework

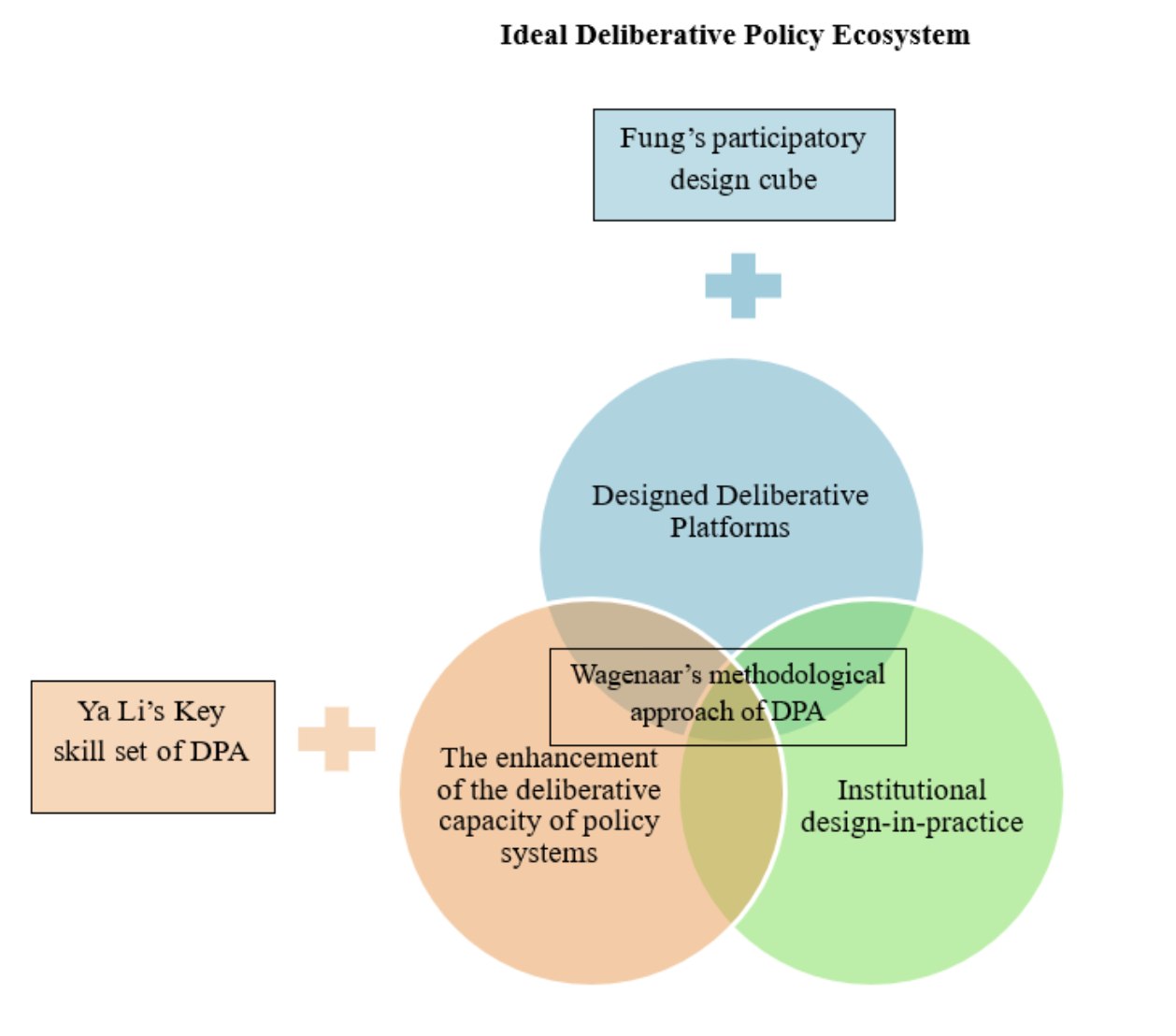

Basic to DPA is a method for bringing together a wider spectrum of citizens, politicians, and experts in the pursuit of policy decisions (Fischer & Boossabong, 2018). The key insight of DPA is that democratic governance calls for a new deliberatively-oriented policy analysis. Traditionally, policy analysis has been state-centered, based on the assumption that central government is self-evidently the locus of governing. However, DPA explores the new contexts of politics and policymaking, examining the influence of developments such as increasing ethnic and cultural diversity, the complexity of socio-technical systems, and the impact of transnational arrangements on national policymaking (Hajer & Wagenaar, 2003). DPA is an approach to policy analysis that emphasizes public participation and deliberation between citizens and officials. It seeks to enhance the deliberative capacity of policy systems and is useful to policymakers, stakeholders, social activists, and researchers alike. Designed Deliberative Platforms (DDP) are an important methodology for working through conflict-ridden policy issues with the affected actors.

Among different DPA approaches, this study adapts Wagenaar’s methodological approach of DPA as the main analysis to frame a critical assessment of existing practices for identifying challenges and propose enhancing public involvement in local government. This approach considers three core angles of DPA, including (1) Designed Deliberative Platforms incorporate Fung’s participatory design cube, (2) the enhancement of the deliberative capacity of policy systems incorporate Ya Li’s DPA skill set and (3) institutional design-in-practice. Thus, the study analyzes the sufficiency and inclusivity of the onsite and online deliberative platforms, the adequate capacity of public servants in facilitating deliberation, and the openness of public organizations to harness horizontal collaboration and bottom-up participation.

Methodology

For the documentary research and primary data collection, interviews were conducted from February to March 2024. This involved 15 Key Informant Interviews (KII) with a diverse group of participants, including local government officers (CDM), members of development affairs committees, representatives from civil society organizations (CSOs), international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), politicians, and scholars who have led local government reforms.

Policy Analysis

In 2010, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, backed by the Tatmadaw, won the election under the Tatmadaw-drafted 2008 constitution. During President Thein Sein’s administration (2011-2015), military leaders transitioned to civilian roles, and policy-making remained centralized among presidential advisors, experts, and government ministers. As a result, people-oriented policymaking was rare. For instance, although President Thein Sein suspended the Myitsone Dam power generation project with China, this did not indicate a shift towards more people-centered policies.

In the 2015 election, the National League for Democracy Party, led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, won with the slogan “Only the people are important.” Her government implemented decentralized policies, promoting direct public interaction through mottos like “Together with the people.” Policies were shaped by citizen input and advice from officials and experts.

Despite the presidencies of U Thein Sein and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi announcing local government establishment, these efforts failed due to the absence of a systematic bureaucratic structure for local governance. Public participation in municipal committees, village administration, and planning processes remained minimal, with poorly defined involvement and a lack of political will for reforms.

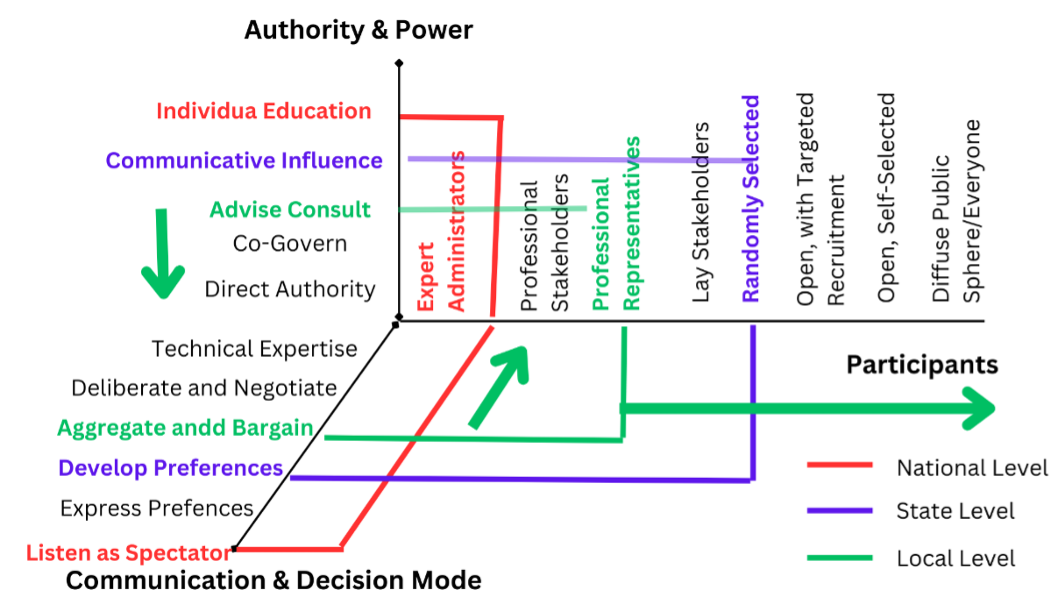

Figure 3. Assessing Myanmar Practices of Deliberation

Source: Archon Fung, Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance (2006)

Based on the KII interviews and assessment, the local level of public participation is significantly better in terms of participants, authority, and communication and decision-making modes compared to state and national levels. This is attributed to the allocation of authority to the local level under the 2008 constitution. It is evident that higher levels of government have less public participation and reduced authority and power to influence policies through public engagement.

- Analysis of Designed Deliberative Platforms in Myanmar

Myanmar’s deliberation strategy faces challenges due to limited public and civil society organization (CSO) participation, affecting the legitimacy of public participation and trust. Visual tools such as Facebook, applications, and websites are used for one-way communication, but they encounter barriers in increasing public engagement. Public participation is constrained by limited space and inadequate representation, which undermines both representation and legitimacy. Communication and decision-making within public committees are hampered by limited representatives, with barriers arising from election processes and committee structures. Discussions often lack influence on government policies due to insufficiently designed platforms for public engagement, highlighting the need for better integration of public input into policy-making.

- Analysis of Enhancing the Deliberative Capacity of a Policy System in Myanmar

Myanmar’s institutional environment for policymaking is hindered by a bureaucratic culture characterized by a ‘Do nothing; be uncomplicated; and avoid trouble’ mentality. This environment is further marred by corruption, low government salaries, a lack of policy initiatives, and highly centralized bureaucratic traditions and norms. Key skills for public administration are developed through centralized training programs designed by the Union Civil Service Board, but there is a need for more effective training support tailored to local government needs. These challenges underscore the necessity of reforming the bureaucratic culture and decentralizing training programs to enhance the deliberative capacity(key skill set of DPA) of Myanmar’s policy system.

- Analysis of Institutional Design-in-Practice in Myanmar

Myanmar’s institutional design faces major challenges due to a lack of interconnectedness and platforms for sharing knowledge and practices. The “Parachute Policy,” which appoints military officers to government positions, creates a hierarchical bureaucracy that stifles innovation and policy entrepreneurship. Relationships between local, regional, and national management are strained by committees often led by the same individuals, leading to capacity and expertise burdens. Organizational rules suffer from outdated laws, corruption, reluctance to work, and lack of accountability, causing high bureaucratic resistance. Additionally, political risks, party priorities, and election-related tensions exacerbate conflicts between politicians and bureaucrats, leading to policy instability.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Myanmar’s current deliberative practices and local governance systems limit public participation, despite policy recommendations. An ideal deliberative policy forum will address these gaps and enhance public participation, legitimacy, and effectiveness in local governance.

Designing the Ideal Deliberative Policy Forum (IDPF)

| Framework | Action by | Implementation Pathway |

| Deliberative Platforms | Forum | 1. Advocate for the involvement of alternative power holders in ethnic armed organization areas to initiate deliberative forums.

|

| Deliberative Capacity | Deliberative Policy Analysts (National, State and Local) | 1. Provide training for community youth to improve facilitation, moderation, and analysis skills.

2. Build local DPA teams to support the forums. |

| Institutional Design-in-Practice | 3 Phases of Forum Design | 3 Phases of Forum Design

Step by Step: – Identify relevant stakeholders (conduct stakeholder analysis). – Select hearing participants to attend an ad hoc forum (representatives of the case). – Ensure equal opportunities for participants to express their voices. – The DPA team provides necessary background information (experts in related fields). Phase 1: – The DPA team facilitates, observes, and analyzes the interests behind positions, appeals, discourses, and metaphors (for narratives and storylines, core evidence). – Conduct debates, dialogues, and deliberations. Phase 2: – Conduct joint fact-finding. – Engage in subsequent negotiations. Phase 3: – Conduct interest-based negotiations (resolution and consensus building). – Provide TPA support for the negotiation process. Final Results: Document the negotiation process and final results, including the consensus reached, the jointly accepted fair scheme, and how people’s views and preferences have been transformed, in the DPA report. Advocate for the DPA report to policymakers. Evaluate the forum design in practice. |

Although the above recommendations are promising guidelines, further studies do the experimentation in the real context. Such action would help moving from this ideal stage to the practical change. The political, social and cultural challenges of deliberative practices in Myanmar also need to be unpacked in order to understand tensions and improve the guidelines.

References

[1] Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public administration review, 66, 66-75.

[2] Fischer, F., & Boossabong, P. (2018). Deliberative Policy Analysis. In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy (pp. 583–594). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198747369.013.39

[3] Hajer, M., & Wagenaar, H. (2003). Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding Governance in the Network Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Li, Y. (2015). Think tank 2.0 for deliberative policy analysis. Policy Sciences, 48(1), 25–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-014-9207-4

[5] Li, Y., & Salecker, L. (2023). Practicing deliberative policy analysis: two cases from China and Europe. Critical Policy Studies, 1-23.

[6] Wagenaar, H. (2022). Deliberative policy analysis. In Research methods in deliberative democracy (pp. 423-437). Oxford University Press.

Download full paper: Click