Assessing the Implementation and Effectiveness of Myanmar's Climate Policy in Coastal Regions: A Case Study of Ye Township

Author: Yin Yin Htwe

Advisor: Thida Chaiyapa

Brief Overview

In the face of rising tides and raging conflict, a crucial climate policy falters, leaving vulnerable communities like Ye Township fighting for survival.

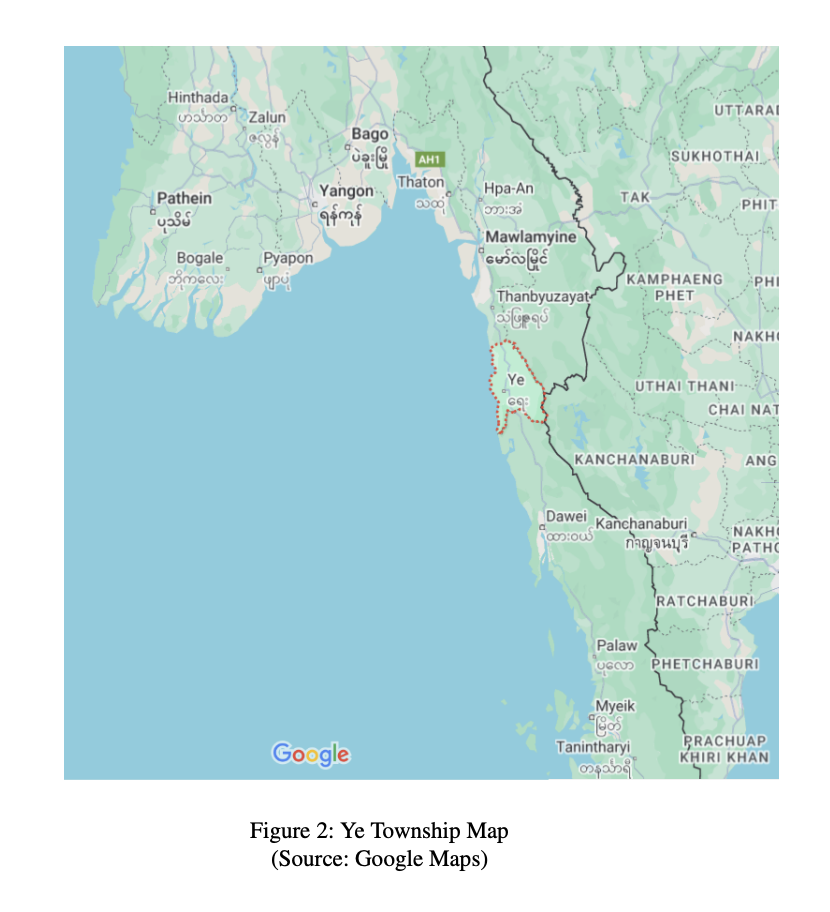

The whispers of the ocean in Myanmar’s southern reaches once promised abundance. However, today, in coastal havens like Ye Township, Mon State, those whispers carry a chilling warning. From the relentless creep of saltwater poisoning rice paddies to the terrifying fury of cyclones, climate change is not a distant threat – it is a daily battle for 152,485 souls on just 1,146 square kilometers of land.

Understanding the Disconnect in Ye

Myanmar’s coastal Ye Township faces escalating climate vulnerabilities, yet its national climate policy (MCCP 2019) remains largely ineffective on the ground. Despite clear environmental impacts and urgent needs, this persistent gap between policy intent and local reality presents a profound, underexplored challenge. This paper uses Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) to dig deeper, moving past surface symptoms to investigate the complex systemic, cultural, and even mythological factors hindering effective climate action here. Unraveling these multi-layered impediments is crucial for crafting truly effective and locally resonant adaptation strategies in such a conflict-affected and resource-constrained region.

Establishing the Significance

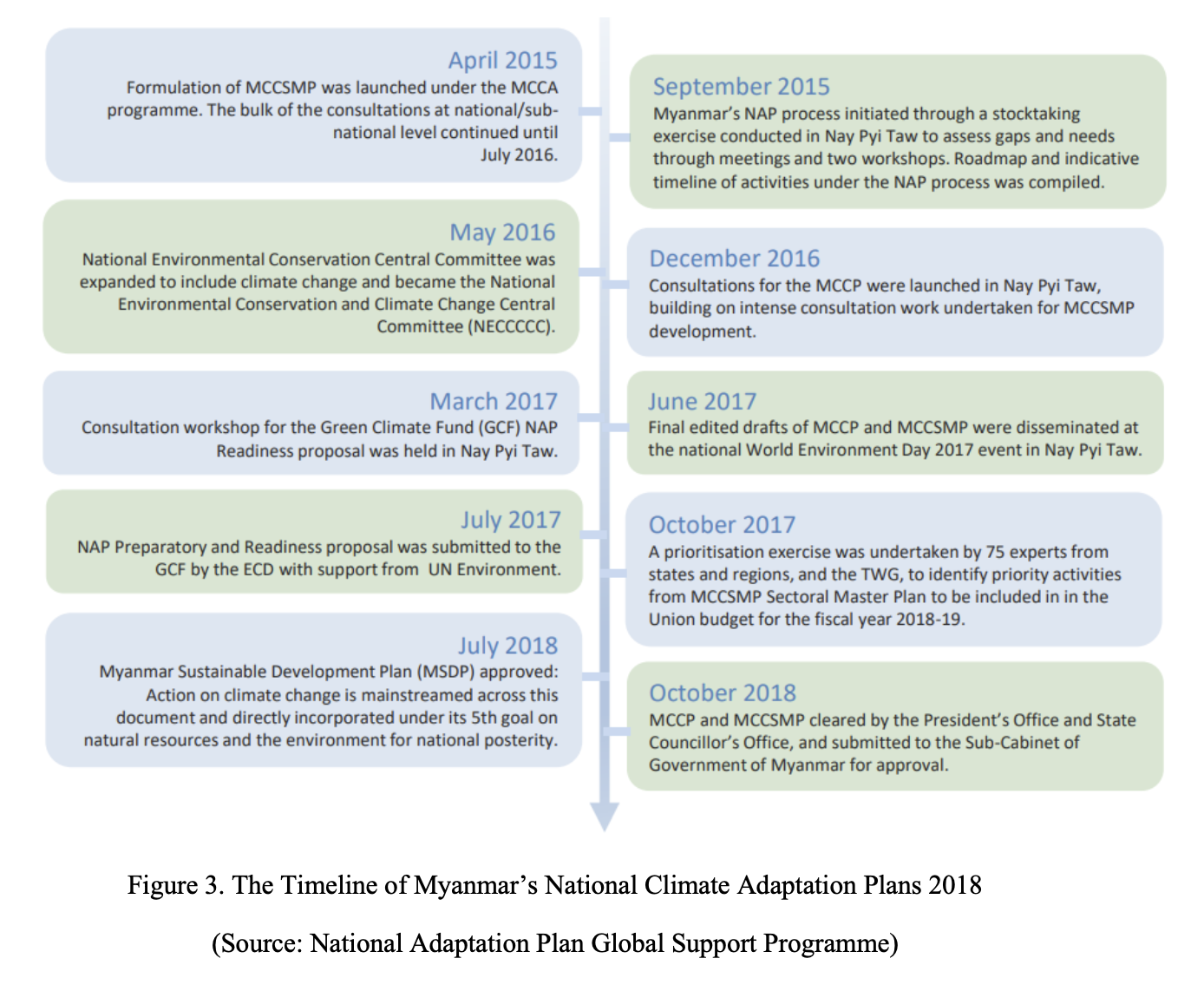

In 2016, Myanmar embraced the Paris Agreement, pledging a future of climate resilience and low-carbon living. The Myanmar Climate Change Policy (MCCP) was formulated through an extensive multi-stakeholder process from April 2015 to October 2018, as evidenced by a timeline of key developmental stages. This process involved numerous national and sub-national consultations, including workshops and stocktaking exercises to assess gaps and needs, highlighting a collaborative approach to policy design. Expert input was prioritized, with 75 specialists contributing to identifying key actions and technical working groups prioritizing sector-specific master plans. Governmental endorsement was secured through clearances from the President’s Office and the State Counsellor’s Office, culminating in its submission to the Sub-Cabinet for final approval. The development was intrinsically linked to national development planning, with climate change actions integrated into the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (MSDP). While the timeline suggests a policy framework encompassing both climate mitigation and adaptation, reflected in the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) processes and engagements with the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the image primarily details the policy’s procedural development rather than its specific mitigation and adaptation activities. The MCCP was born from noble aspirations: to protect a nation ranked the fourth most natural disaster-prone country globally between 1993 and 2022. Its goals were ambitious: reduce climate effects, weave climate thinking into national priorities, and foster green, inclusive growth. Yet, in places like Ye Township, the policy’s promise feels tragically distant. Why? Because the blueprint, however well-intentioned, carried critical flaws from the start.

The Perfect Storm: Climate, Conflict, and Chaos

As the climate crisis intensifies – with temperatures projected to rise by 2.07°C by 2060, potentially leading to more frequent floods, droughts, and crop failures – a new, devastating force has gripped Myanmar: the 2021 coup.

This is not just a political upheaval; it is a direct threat to climate resilience. The ongoing civil wars and the rise of ethnic armed organizations resisting the State Administration Council have unleashed a cascade of environmental degradation:

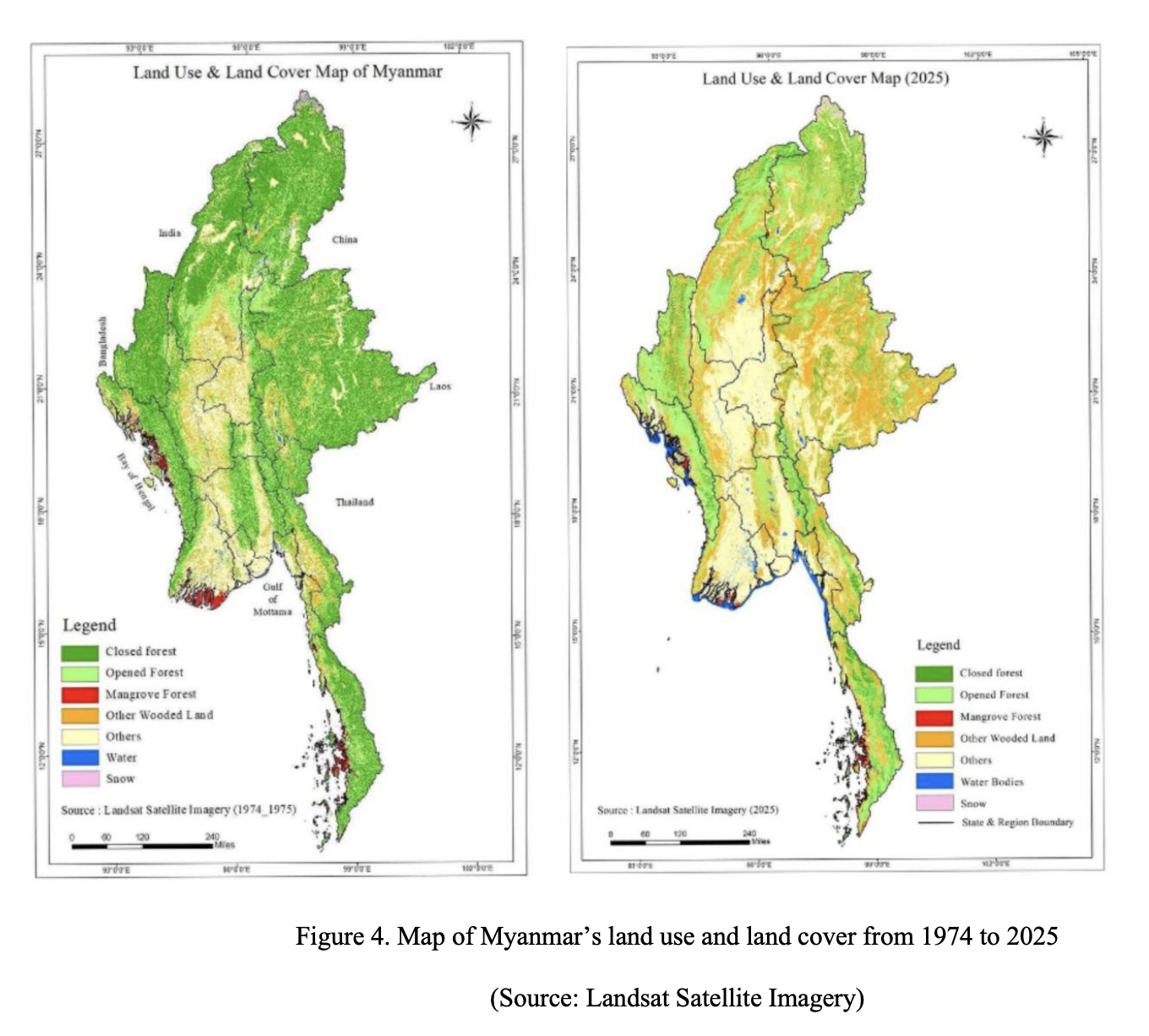

- Rampant Deforestation: Figure 3 starkly illustrates Myanmar’s alarming loss of closed forests from 1974 to 2025 – a direct consequence of conflict-driven illegal logging and land conversion.

- Politicized Aid: Humanitarian aid and disaster response are reportedly politicized, and used by armed groups to consolidate power, leading to uneven and often blocked support for disaster-affected areas.

- Vulnerable Populations on the Brink: War refugees, internally displaced persons (IDPs), Indigenous communities, women, and migrants are disproportionately affected, and their existing vulnerabilities are dramatically exaggerated.

- Broken Infrastructure: Myanmar’s transportation sector, vital for aid and access, saw CO2 emissions surge to 3 million tonnes in 2023, with 73% from domestic transport. This growth, coupled with climate impacts, leaves areas like Ye Township exposed to severe road accessibility issues, cutting off essential services.

The World Bank (2024) stated that the Yagi typhoon and monsoon floods destroyed 3.5 percent of agricultural lands, displaced over two million people, and caused one million to face food insecurity. The climate impacts also disrupted production and caused other shortages in 2024. Because of the flood and typhoon hazards, thirty-four percent of farmers reported losing access to their lands, and 65 percent of firms surveyed said they encountered electric outages within three months, which cost them power maintenance expenses (World Bank, 2024).

The story of Ye Township mirrors Myanmar’s complex struggle. Here, on a vulnerable coast, the intensifying realities of climate change collide with a turbulent political landscape. National climate policies, even those well-intended, often falter, unable to translate into meaningful local action. This critical disconnect isn’t just a matter of oversight; it’s a symptom of deeper, intertwined issues that demand a nuanced approach.

Unearthing the Layers: A CLA Perspective

To truly grasp this dilemma, the author employed Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), a method that digs beneath the surface to reveal the hidden forces at play.

On the Litany Layer, the immediate crisis in Ye is stark: a critical lack of accessible environmental education. Local libraries and education centers are woefully limited, leaving most youth and residents in the dark about climate change’s impacts and how to respond. It’s a foundational deficit that leaves the community exposed and ill-equipped.

Venturing deeper, the Systemic Causes Layer exposes the unraveling foundations. The crucial work of maintaining forests and green spaces is disrupted, leading to widespread degradation and the erosion of traditional conservation practices. This breakdown isn’t accidental; it’s a direct consequence of Myanmar’s political unrest and ongoing civil war, which consistently push environmental concerns aside in favor of immediate peace talks, allowing unchecked exploitation to continue.

Beneath these systemic disruptions lies the Worldview Layer, where conflicting realities shape local responses. Many youths, the future custodians of this land, have become “disheartened navigators,” hesitant to express their environmental knowledge, perhaps feeling a sense of futility. Compounding this, marginalized groups are routinely excluded from decision-making, silencing voices and overlooking crucial local insights that could drive effective adaptation.

At the very core, the Myth and Metaphor Layer reveals the prevailing, unconscious belief guiding Ye’s actions: “Security, safety, and food come first, then climate change preparation is the last to consider.” This powerful narrative, born from immediate existential threats, fundamentally prioritizes short-term survival. It’s a lens through which all other challenges are viewed, explaining why environmental concerns are so often deferred amidst political strife and why individual actions lean towards immediate gain over long-term ecological preservation.

Recommendations

In light of the prevailing political complexities, four distinct policy approaches are recommended for Myanmar’s coastal regions. These initiatives, inherently complex, are designed for implementation through multi-level governance frameworks and include one that embodies principles of neutral policy design. They offer viable pathways for both Myanmar’s future Federal Government and non-governmental organizations:

- Empowering Every Voice: It is crucial to take into consideration marginalized groups, including women participants and religious leaders when making decisions and operating policy processes. They play a vital role and make a lot of impact along the way. For example, in the Mon community, people will not pay enough attention to the municipality’s procedure when it comes to rules and regulations, such as forbidding cutting down a tree or throwing trash. However, when a religious leader, a respected monk, recommended conserving trees or being realistic with managing garbage, almost all people followed his suggestion. Since climate change affects women differently, only women can bring the burden to the discussion table and tackle maternal risk, overwork, sanitation needs, and so forth. Although women are more vulnerable to climate crises than men, they are also caregivers and natural resource managers, so they can bring inclusive perspectives to the table.

- Local Knowledge, Local Power (Training & Awareness): From teenagers to farmers, at least basic climate change adaptation and risk reduction training are essential to protect coastal areas and sustain the local livelihood. It is arranged and managed with the support of local governmental and community-based organizations to deliver a well-planned three-day training about early warning signs of potential water scarcity, floods, heavy rain, droughts, etc. To each coastal society, by providing awareness of how smartphones are capable of collecting information and are handy in terms of hunting for climate data, news, foresight reports, and for other emergency responses. Moreover, the coastal region becomes less fragile regarding precautionary measures, preparation, and evacuation processes after each training session. It is important to monitor and evaluate such training once a year and provide such basic training to coastal regions to build a sustainable and healthy environment.

- The Green Wall (Restoring Mangroves): The establishment of mangroves is inevitable for effective coastal protection and mitigation against the severe impacts of climate-related disasters, including erosion, storms, sea level rise, and floods. Beyond their protective functions, mangroves foster significant biodiversity, sustain healthy ecosystems, and generate livelihoods for coastal inhabitants, including fishermen and those engaged in aquaculture. With the government and locals’ cooperation and collaboration, it is crucial to restore the existing mangrove trees and their acres around coastal areas.

- Universal Climate Hazard Data Platform: This policy advocates for the establishment and maintenance of a robust, publicly accessible digital platform that aggregates, standardizes, and disseminates critical climate hazard data and information relevant to coastal communities, including Ye Township. This platform would provide detailed, localized data on past, current, and projected climate impacts such as sea-level rise rates, historical flood maps, storm surge probabilities, drought severity indices, and localized real-time weather forecasts. The information would be presented in multiple, easily digestible formats (e.g., visual maps, simple language summaries, data tables) to cater to diverse user needs.

Forging a Resilient Future: Proposed Policies and Implementation Roadmaps

-

Empowering Every Voice

Forging resilient communities means ensuring every voice counts. Over 5-10+ years, this initiative fundamentally shifts how decisions are made. It begins by formalizing Community Councils and Village-level Committees in Phase 1 (1-3 years), ensuring diverse voices—especially from women, youth, religious leaders, and Indigenous communities—find avenues to be heard. Local CSOs and CBOs serve as key partners, guiding dialogues and building grassroots capacity. As the initiative expands in Phase 2 (3-7 years), regular Multi-Stakeholder Forums institutionalize collaboration, with international NGOs offering vital oversight and technical aid. By Phase 3 (7+ years), participatory governance becomes deeply woven into local functions, fostering independent community advocacy. This approach directly boosts social equity, legitimizes governance, and tailors solutions to local realities, ultimately enhancing human security and optimizing resource use. While there are initial administrative costs and potential resistance from dominant groups—plus the risk of tokenism—the long-term gains in social cohesion and disaster reduction promise substantial economic benefits.

-

Local Knowledge, Local Power (Training & Awareness)

Building true community resilience starts with knowledge. Over 3-5 years, this policy empowers coastal communities, especially youth and farmers, through targeted climate adaptation and risk reduction training. Phase 1 (1-2 years)involves assessing local needs and developing curricula that blend scientific insight with traditional wisdom, piloting programs focused on climate literacy and basic disaster preparedness. In Phase 2 (2-4 years), these programs expand to wider areas, diversify modules to cover climate-resilient agriculture and water management, and empower local leaders through robust “train-the-trainers” initiatives. The long-term vision for Phase 3 (4+ years) is to embed climate education directly into local schools and community centers, fostering a continuous learning culture. Key partners like Local Education and Agricultural Extension Departments, CBOs, Farmers’ Associations, and Youth Groups lead the charge, supported by Universities for curriculum and Telecommunications Companies for mobile outreach. This direct investment in skills strengthens community bonds, reduces disaster losses, and boosts agricultural productivity, laying a strong foundation for enduring adaptation, despite initial resource strains or reach limitations.

-

The Green Wall (Restoring Mangroves)

A “Green Wall” of restored mangroves offers an indispensable defense for coastal communities, representing a crucial long-term investment unfolding over 10-20+ years. Phase 1 (1-3 years) focuses on ecological assessments to find ideal sites, engaging communities in comprehensive planning and site preparation, establishing nurseries, and securing initial funding. In Phase 2 (3-7 years), large-scale planting begins across identified coastal areas, with local Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) and Mangrove Protection Committees taking charge of protection and monitoring. This phase also focuses on developing sustainable livelihood alternatives, from responsible aquaculture to eco-tourism. By Phase 3 (7+ years), the mangroves mature, providing robust protection and full ecosystem services, which require ongoing ecological monitoring and sustainable financing. This grand effort relies on strong collaboration among CFUGs, Environmental NGOs (for technical expertise), Forestry and Fisheries Departments (for legal and resource management), the private sector (for eco-tourism and sustainable seafood investment), and even Microfinance Institutions to support alternative livelihoods. While initial costs and land-use conflicts are direct challenges, the overwhelming long-term benefits in coastal protection, carbon capture, job creation, and food security make this a vital investment.

-

Universal Climate Hazard Data & Information Platform

Building a Universal Climate Hazard Data & Information Platform offers vital, democratic access to critical climate insights, serving as a strategic utility phased over 5-7 years. Phase 1 (1-2 years) involves designing and building the core digital platform, integrating existing historical and real-time hazard data, and creating user-friendly mobile interfaces for pilot locations. Phase 2 (2-4 years) expands access to wider communities, diversifies data sources with local observations, and develops early warning functionalities, alongside extensive user training. By Phase 3 (4+ years), the platform will evolve to include advanced predictive modeling, integrating directly into local development plans and fostering a continuous culture of data-driven decision-making. Key actors include Meteorological and Hydrology Departments providing raw data, Telecommunications Companies ensuring widespread access, and Technology Companies building the platform itself. Crucially, Community Information Centers (like local libraries) and Local CBOs/NGOs act as vital grassroots facilitators for data interpretation. This platform directly boosts public awareness and empowers individuals for planning, economically reducing disaster losses, and attracting investment confidence, laying a neutral, evidence-based foundation for long-term adaptation.

Concluding Thoughts

The study of Ye Township is, in many ways, the story of Myanmar’s unfolding future. It’s a stark reminder that even the most well-intentioned national policies, like those designed for climate resilience, can falter when disconnected from the ground truth, especially when compounded by profound political upheaval and a desperate fight for survival. In such complex and volatile environments, the traditional top-down mandates prove insufficient. The struggle against climate change in these vulnerable coastal communities demands a more nuanced approach, one rooted in multi-level governance that acknowledges the intricate interplay of actors from local communities to national bodies. Success hinges on bridging critical gaps, ensuring policies are not just theoretically sound but genuinely implementable and effective on the ground.

Therefore, the path forward for Ye, and indeed for Myanmar’s imperiled coastlines, lies in a bold, bottom-up transformation. This necessitates empowering the forgotten voices from within the communities, embracing their ancient wisdom and local knowledge through targeted training and robust data sharing, and investing strategically in nature’s formidable defenses, like the resilient mangroves. This holistic approach, combining equitable participation with informed, localized action, recognizes that the security of Myanmar’s people, their livelihoods, and their land are inextricably linked to the health of a planet under siege. The urgent question is not just if Myanmar can adapt, but how quickly it can rally its true strength – its diverse people – to rebuild a safer, greener future from the shores up.

References

- Aung, S. Y. (2019, August 20). Fatal landslide raises alarms over Myanmar’s natural disaster preparedness. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/fatal-landslide-raises-alarms-myanmars-natural-disaster-preparedness.html

- Asian Transport Outlook (ATO). (2024). Transport and Climate Profile: Myanmar, https://asiantransportoutlook.com/analytical-outputs/countryprofiles/

- Department of Population, Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population. (2017, October). The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census, Mon State, Mawlamyine District, Ye Township Report. https://www.dop.gov.mm/sites/dop.gov.mm/files/publication_docs/ye_update.pdf

- Germanwatch. (2025). Climate Risk Index 2025: Impacts of Extreme Weather Events. Retrieved fromhttps://www.germanwatch.org/en/cri

- Institute for Sustainable Communities. (2019, December 19). The Myanmar Climate Change Policy (EN & MY). https://policy.asiapacificenergy.org/node/4245#:~:text=The%20Myanmar%20Climate%20Change%20Policy,all%20levels%20and%20sectors%20in

- John, P. C. (2012). Analyzing Public Policy (2nd Edition). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203136218

- Nang, S., & Beech, H. (2019, August 11). Landslide kills at least 51 in Myanmar, with more heavy rain on the way. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/11/world/asia/myanmar-landslide.html

- National Adaptation Global Support Programme. (n.d.). National Adaptation Plans in focus: Lessons from Myanmar. https://www.globalsupportprogramme.org/resources/project-brief-fact-sheet/national-adaptation-plans-focus-lessons-myanmar

- Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), & Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). (2024). Climate, Peace, and Security Fact Sheet: Myanmar. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/01_sipri-nupi_fact_sheet_myanmar_may_0.pdf

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation. (2021, June 20). National Unity Government, Myanmar. https://monrec.nugmyanmar.org/environmental-conservation-department/

- Oo, B. N. (2024). Communities’ Responses to Land Commodification Post-peace Process. Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD), Chiang Mai University https://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/cpri-24-mon-state-land-banyar-oo-with-covers.pdf

- Open Development Myanmar. (n.d.). Government. Open Development Initiative. https://opendevelopmentmyanmar.net/topics/government/#:~:text=Myanmar’s%20national%20government%20is%20divided,state%20and%20head%20of%20government

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. (2017). United Nations Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/

- United Nations, H. (2019, May 24). Myanmar Climate Change Master Plan (2018-2030). United Nations Myanmar. https://myanmar.un.org/en/25466-myanmar-climate-change-master-plan-2018-%E2%80%93-2030#

- World Bank. (2024, December). Myanmar economic monitor: Compounding crises. Special focus: International migration from Myanmar. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099121024092015654/pdf/P50720310fc16e0251ba691e1227abb7375.pdf

Download full article: Click