Redefining Displacement Issues: Lessons from the Shortcomings of the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction Act

Author: Giles Jan L. Viojan

Advisor: Ora-orn Poocharoen

Introduction

Threats to human life brought by violence and natural hazards continue to be the leading factors of displacement in the Philippines. According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), over 9 million Filipinos were displaced by typhoons in 2024 alone (IDMC, 2025). Meanwhile, the civil war between the Communist Party of the Philippines- New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) and the Philippine military continues to displace the Philippine population in the countryside (Fernandez & Magbanua, 2020; Punongbayan & Dumlao, 2024).

However, despite internal displacement being an unfortunate fact that the country faces, there are no proper frameworks in the country for it. In place of legislation dedicated to tackling the issue, the Philippine government is instead using the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act (PDRRMA)– a legislation implemented to heighten the local government unit’s (LGU) autonomy in times of disaster. This approach, however, has been criticized for being inadequate in addressing the needs of internally displaced people (IDP) (Bermudez, Temprosa & Benson, 2018; Ferrer & Lagos, 2019). For instance, in the wake of the occupation of Marawi City in Mindanao, Philippines the framework has been criticized as through it, the IDPs were treated no more than people to be rehomed and relocated (Bermudez, Temprosa & Benson, 2018). In this case, it was revealed that a disaster approach to address internal displacement leads to disastrous results. As the country becomes ever more vulnerable to natural hazards and armed conflict, there is a pressing need to revisit and refine current strategies in dealing with displacement to ensure that nobody, most especially in the periphery of the Philippine society, is left behind.

This policy brief aims to reimagine the issue of displacement in the context of the Philippines and present new ideas on how to address it. Creating an overarching framework for displacement is challenging even though there are established international standards for it due to problems of locality and context (McNeill et al., 2022). This policy brief overcomes this by basing its analysis on the data gathered from five interviews and a focused-group discussion with the IDPs in Samar last May 9, 2025. In the following part of this paper, the problem statement, I will enumerate several criticisms of PDRRMA as a framework of displacement. In this section, I explore its shortcomings owing to its primarily organizational nature and start unpacking the notion of displacement as an institutional issue as well as that of self-agency. The third section of the paper contains the results and analysis of the data gathered. By using the Causal Layered Analysis as a framework (CLA), I aim to deconstruct the imaginings of IDPs of their present predicament and anticipated future challenges. Following this is the policy implication of centering IDPs in the displacement issue, and lastly, the policy recommendations that aim to address the analyses on the four layers of the CLA.

The Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act and the disastrous handling of IDPs

The Philippine government lacks laws and policies that prescribe how the local government units and other government agencies should address the issue of internal displacement. Currently, the Philippine government is using the PDRRMA, a framework that was created and used to “manage” “natural” disasters in the country. The PDRRMA gives LGUs experiencing disasters more autonomy from the national government to respond to disasters. By design, and by practice, PDRRMA enables an efficient top-down management of issues at the local level. While it is necessary in events riddled with high levels of uncertainty and that require immediate attention, such as times of disasters, the PDRRMA leads to misguided solutions on issues that require the understanding of marginalized groups that are experiencing protracted and periodic displacement.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has criticized this approach for not having a rights-based approach which they deemed necessary in dealing with the issues that involve internally displaced people (IDP) and internal displacement in general (Bermudez, Temprosa, & Benson, 2018). Furthermore, the resulting top-down management of displacement leads to further challenges such as improper policy strategies and politicking of government resources. For instance, aside from slow progress, the aid to IDPs in Marawi City in Mindanao has been criticized for diluting the nuances of the experiences of people in displacement. According to Bermudez, Temprosa, & Benson (2018), the policies implemented simplified the issue of displacement to a mere issue of rehoming, intentionally ignoring the challenges faced by the religious, gender, ethnic and economic minorities that survived the occupation of the City. Additionally, the autonomy that the LGU enjoys through the PDRRMA fosters an environment ripe for corruption (Adams & Neef, 2019). Supporters of LGU officials tend to be favored over other groups of people. This is especially true in the Philippines where clientelism is an enduring salient feature of the country’s political ecosystem (Aspinall & Hicken, 2022).

Causal layered analysis: institutionalized inequalities, IDP disenfranchisement, perceived helplessness, and displacement

The Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) is a tool that allows one to consider and analyze issues at varying ontological levels and epistemological traditions (Inayatullah, 1998). CLA’s main strength is not with its forecasting capabilities, but rather its ability to “undefine” different futures through a careful analysis of the past and present facts, systemic causes, the world views that are shaped by them, and the personal and internal stories that fuel them (Inayatullah, 1998). And so, rather than just exclusively problematizing the future; what is the future, or what should the ideal future be; it also seeks to understand how the future is presently being constructed.

In the case of displacement in the Philippines, mismanagement has made it difficult for IDPs to forge a path forward. To create a policy mix that aims to empower IDPs while challenging current institutionalized strategies, the CLA is used to analyze how past and present predicaments experienced by IDPs form a barrier that inhibits them from moving forward. Using CLA’s main feature of analyzing an issue at multi-ontological and epistemological levels, this paper aims to dissect the issue, and later present a more apt strategy for displacement. The proceeding part of this section divides the analysis into the four layers of the CLA—litany, social factors, worldviews, and myths. Using the data I gathered through interviews and FGDs in May 2025, and document analysis I found that at the litany, the Philippines is one of the worst countries at handling IDP issues; at the systems level, the fact that there are no displacement specific law posed a challenged for responding to displacement issues; at the worldview, an anticipatory framing of displacement is problematic; and the myth of putting too much premium on humbleness is detrimental to IDPs. These are summarized in Table 1 below.

Litany

The litany is the first layer of the CLA and often deals with the empirics of a certain issue. It pertains to the conventional knowledge, meaning, those that could be seen in media, and is often used for political ends to illicit people’s reactions (Haigh, 2016; Inayatullah, 1998). It includes but is not limited to, statistical “facts”, rankings, and the like.

The lack of a framework for displacement continues to make the lives of IDPs in the Philippines even more difficult. In 2025, the number of IDPs in the country increased by 1 million due to heightened threats brought by storms, other natural hazards, and ongoing violence and conflict in the country (Ordinario, 2025). The ongoing challenges in aiding the IDPs are even more apparent for people who are already very vulnerable to such issues. According to UNICEF (2023), the highest number of displaced children was recorded in the Philippines in 2023. On the other hand, displacement serves as a detrimental exponential factor for women who already face other forms of violence (e.g. sexual) (Sifris & Tanyag, 2019).

Furthermore, the lack of framework also leads to government programs failing to catch the nuances of the needs of different sectors of the displaced population in the country. Often, the government just doles out the same type of aid regardless of social realities (Collado & Arpon, 2021). This gives out the impression that IDP protection is a matter of crossing a checklist, rather than prioritizing that IDPs receive the aid that they need. For a country like the Philippines where family and community are an integral part of societal norms, this is an injustice. Indeed, in one of the focused-group discussions, an informant lamented the fact that households are the basis for how much aid one will receive. For their group composed of six families under one roof, this meant that, effectively, the aid that they received was only enough to support one family. These instances illustrate how the lack of a framework becomes a barrier to achieving (transitional) justice in the context of periodic and protracted displacement in the Philippines.

| CLA on Displacement on Challenges posed by PDRRMA as a displacement framework | |

| Litany | Philippines as one of the worst countries at handling displacement issues. |

| Systems | No displacement specific framework |

| Worldviews | Anticipatory definitions of displaceability |

| Myth | Over-humbleness: he who always bends, never learn to stand back up |

Table 1. CLA on the Philippine government in handling displacement issues

Social factors: No displacement specific framework

There is no shortage of criticisms for the failures of the implementation of the Philippines Local Government Code (Atienza & Go, 2023; Shair-Rosenfield, 2016; Tadem & Atienza, 2023). Instead of empowering local government to implement apt policies with the needs of local communities in mind through decentralization, the newfound discretion brought by this legislation becomes a leeway for unequal and unfair resource redistribution by local authorities (Adams & Neef, 2019; Yilmaz & Venugopal, 2013). During my interview, one of the most common themes was how they noted that other families who have supported the campaign of the incumbent local politicians receive more aid compared to others. In the case of one informant who was against the incumbent politician, they got removed from the list of beneficiaries and had to campaign for themselves to be included. The shoddy implementation of local government unit decentralization coupled with the absence of a proper framework for IDPs institutionalizes and arguably formalizes inequality.

Worldviews: displaceability restricted by an anticipatory mindset

Here the subjects of analysis are the discourses that frame and sustain the empirical aspect of issues (Riedy, 2008). There is an obvious movement in the analysis at this level compared to the previous two: While the first and second layers are mainly concerned with the observable events and trends that often characterize a specific problem, the third level aims to explain how these problems emerged and are being framed by looking at the ideological discourses that surround them (Inayatullah, 1998; Riedy, 2008). (state what is the worldview directly, and why it is a problem)

Whereas traditional displacement and refugee studies have always been concerned with the event of forced movement of people (Cantor & Wooley, 2020), the scholarship on displaceability adds nuance by looking at systemic, cultural, and socio-political factors that contribute to the likelihood of people being displaced (te Lintelo & Hemmersam, 2024). While this is a welcome development, it remains anticipatory and reactive; and does not consider the very important factor of people’s capability to move beyond their displacement. As evident in the case of PDRRMA in the Philippines, efforts to develop resilience through increased autonomy alone is not enough especially when IDPs are not empowered to forge their paths. The view that displacement issues start with their triggers and end with relocation and resettlement is detrimental to the IDPs in the Philippines.

My data suggests that the IDPs faced significant challenges due to not having ample support to make their own decisions. Aid only came in the form of food packs– which in some cases are not even enough for their daily needs. To overcome these challenges, they resorted to pooling resources. The IDPs pooled their resources together and amended each other’s deficiencies. However, this is only about food. Individuals who lost their government papers due to being forcibly displaced, do not know how to get and where to get support.

Aside from this they also suffer from being removed from their communities. Rural areas in the Philippines are incredibly tight-knit. After being separated from their communities, the IDPs expressed longing and being estranged from their new communities. One specific informant expressed that although she is doggedly eager to revert to what was normal for them, losing her community disorganized her daily practices further.

Myth: he who always bends, will never learn to stand back up

Lastly, the deepest level of the CLA is the myths and metaphors. Tackling this layer requires a thorough understanding of the issue as it deals less about the rational and logical, and pertains more to the emotional spectrum of knowledge, and ways of knowing.

After five interviews and one focused group discussion, the myth that arose pertained to the IDP’s over-humility. When asked how they felt about the situation they are in as IDPs, they expressed feelings of frustration and sadness, and also sentiments that despite these, it is just normal for them to suffer like this. Particularly they most often responded with the words, “kami manla ini”, a waray-waray phrase that when translated to English is “this is just who we are”. The phrase itself signifies disregard for their self-importance. They use the term to somehow justify government neglect of their situation, although unintentionally. By saying “kami manla ini” when asked in relation to the insufficient aid they receive, they are expressing that they deserve to be neglected for being farmers, people in poverty, and for living in the rural areas– people who are widely construed to belong in the margins of the Filipino society.

Humility and respect for elders and people in power are a big part of the upbringing of Filipinos especially among relatively conservative families. A popular proverb in the country is the proverb “the bamboo that bends in the storm is stronger than the oak that resists”, a metaphor for the benefits of flexibility, docility, and submissiveness. This is especially more popular in the Philippines where we experience over 20 storm landfalls yearly which gives it another level of enhanced relatability for locals. Taken differently, the proverb could also be a defeatist narrative, especially for those who are so powerless that they do not have a choice but to bend every time. Hence “he who always bends, never learn to stand back up” is an apt metaphor that captures the overarching theme captured by the data that I gathered.

Policy implication

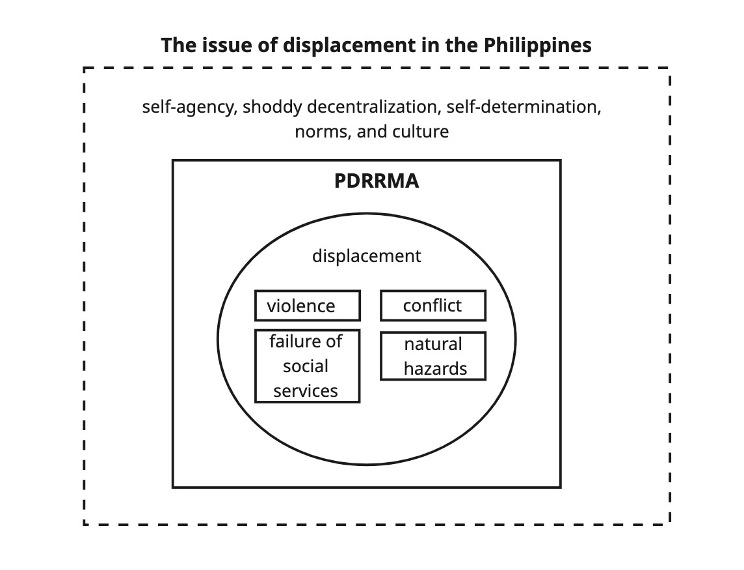

A causal layered analysis of the application and implementation of the PDRRMA revealed that it is not able to respond to the nuances of displacement issues in the Philippines. The PDRRMA as a framework is unhelpful to the plights of the IDPs at the least, and at best, is only anticipatory and not transformative. The framework only factors in four general factors in addressing displacement, namely, conflict; violence; failure of social provision; and natural hazards. Even then, data suggests that it does not do so well as politicking makes it less sensitive to causes of failure in social provision and aid. This treatment of displacement as triggers, and response to those triggers being mere allocation, provision, and management of resources does not reflect the real experiences– the challenges and needs– of the IDPs. Its failure to address displacement as an issue is attributed to its inherent incapability to recognize that the issue is beyond the organization.

Furthermore, the data suggest that there are other considerations to displacement as an issue. Primary in this is seeing displacement as an issue of self-agency, and self-determination that has institutional and cultural roots. Contrary to the framing of PDRRMA, that post-displacement imaginaries are mainly about rehoming, I argue that a new displacement framework in the Philippines should also make a point in ensuring that people are not stuck in limbo within their country. That people are empowered to make choices that will move them beyond the fact of being IDPs. I present these ideas in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Analysis: current and envisioned framing of the displacement issue in the Philippines

Policy recommendations

The following recommendations are suggested to be implemented in the medium to long term. There are two policy recommendations; the first is the incorporation of NGOs into the framework, and the second is a reframing of the issue of displacement. These recommendations are in consideration with the policy implications above that were derived from a causal layered analysis of displacement.

Incorporating NGOs into the framework

To solve the issues of lacking social support, and institutionalized inequalities, and to initiate the rewriting of the current myth, the government could formalize the incorporation of non-government agencies (NGOs) into the framework. The role of NGOs in the context of displacement in the Philippines currently is limited to the provision of social services and goods when the government cannot do so. Albeit important, NGOs play a small part in what they can offer. NGOs have two main purposes in the displacement response and context; to be a source of information and to be a watchdog to prevent inequalities brought by partisan politics; and to increase levels of deliberation.

NGOs are in a great position to ensure a just response to IDP issues. They will act as a third actor that will help protect the rights of IDPs while ensuring smooth government provision. Additionally, NGOs are a source of wisdom and expertise. Various NGOs have experience in dealing with different challenges, and this could be an asset in improving the IDP framework in the Philippines. A similar initiative has been implemented in Vietnam whereby NGOs inform government response to various issues (Center for Excellence in Disaster Management, 2021).

The second role of NGOs is to empower the IDPs; to give them a platform to raise their voices, and to make the policy more deliberative. This is especially important in the context of the overly humble Filipinos who cannot, and do not, contradict policies implemented by the government. Hopefully, by making IDPs more empowered, they will then be more capable of making choices for their benefit. This could be mobilized by including NGOs as one of the actors that directly respond to these issues like the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), and the Department of Interior and Local Governance in the Philippines.

Reviewing PDRRMA as a displacement framework: Tawo Anay (People first)

The second policy recommendation is to revise PDRRMA’s framing of displacement. Instead of focusing on the triggers of displacement and reactive responses to it, the new framework should center the issue of displacement on the IDPs– on the people who are themselves affected. Aside from thinking of resettlement, relocation, and provision of social services, the new framework should also make sure that people are given ways to find themselves after being displaced. A liberating framework for IDPs is one that not only satisfies biological needs, but also provides solutions to cultural, and institutional difficulties of being IDPs.

References

- Adams, C., & Neef, A. (2019). Patrons of disaster: The role of political patronage in flood response in the Solomon Islands. World Development Perspectives, 15, 100128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2019.100128

- Aspinall, E., & Hicken, A. (2022). Guns for hire and enduring machines: Clientelism beyond parties in Indonesia and the Philippines. In Varieties of Clientelism. Routledge.

- Atienza, M. E. L., & Go, J. R. G. (2023). Assessing Local Governance and Autonomy in the Philippines: Three Decades of the 1991 Local Government Code. UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES CENTER FOR INTEGRATIVE AND DEVELOPMENT STUDIES. https://cids.up.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Assessing-Local-Governance-and-Autonomy-in-the-Philippines.pdf

- Bermudez, R., Temprosa, F. T., & Benson, O. (2018, October 17). A disaster approach to displacement: IDPs in the Philippines – Commission on Human Rights, Philippines. Chr.Gov.Ph. https://chr.gov.ph/a-disaster-approach-to-displacement-idps-in-the-philippines/

- Cantor, D. J., & Wooley, A. (2020). Internal Displacement and Responses at the Global Level: A Review of the Scholarship—SAS-Space. https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/9356/

- Center for Excellence in Disaster Management. (2021). Vietnam: Disaster Management Reference Handbook. Center for Excellence in Disaster Management. https://reliefweb.int/report/viet-nam/disaster-management-reference-handbook-vietnam-december-2021#:~:text=Vietnam%20is%20implementing%20a%20multi,million%20in%20disaster%20relief%20assistance.

- Collado, Z. C., & Arpon, A. T. (2021). Single-Mothering as a Category of Concern in Times of Displacement: The Case of Internally Displaced Persons in Southern Philippines. Journal of Social Service Research, 47, 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1869139

- Ferrer, R. M., & Lagos, D. T. (2019). What Makes a Community: Displaced People’s Sense of Community and Human Rights in Resettlement. Philippine Journal of Social Development, 11, 51–81.

- Haigh, M. (2016). Fostering deeper critical inquiry with causal layered analysis. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 40(2), 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2016.1141185

- Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method. Futures, 30(8), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. (2025). Philippines. IDMC – Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Retrieved May 20, 2025, from https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/philippines

- Lischer, S. K. (2007). Causes and Consequences of Conflict-Induced Displacement. Civil Wars, 9(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240701207302

- Magbanua, E. F., Williamor. (2020, October 29). 50 families displaced by clash between Army, NPA in Cotabato town. INQUIRER.Net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1353839/50-families-displaced-by-clash-between-army-npa-in-cotabato-town

- McNeill, I., Amin, A.-A., Son, G., & Karmacharya, S. (2022). A lack of legal frameworks for internally displaced persons impacted by climate change and natural disasters: Analysis of regulatory challenges in Bangladesh, India and the Pacific Islands. https://doi.org/10.25330/2504

- Ordinario, C. U. (2025, May 13). PHL sees over 9 million internally displaced by disasters and conflict in 2024, says report. BusinessMirror. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2025/05/13/phl-sees-over-9-million-internally-displaced-by-disasters-and-conflict-in-2024-says-report/

- Palagi, S., & Javernick-Will, A. (2019). Institutional constraints influencing relocation decision making and implementation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 33, 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.10.016

- Punongbayan, M., & Dumlao, A. (2024, April 4). AFP, NPA clash: Hundreds flee homes in Abra town | Philstar.com. Philstar.Com. https://www.philstar.com/nation/2024/04/04/2345117/afp-npa-clash-hundreds-flee-homes-abra-town

- Riedy, C. (2008). An Integral extension of causal layered analysis. Futures, 40(2), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2007.11.009

- Shair-Rosenfield, S. (2016). The Causes and Effects of the Local Government Code in the Philippines: Locked in a Status Quo of Weakly Decentralized Authority? Journal of Southeast Asian Economies, 33(2), 157–171.

- Sifris, R., & Tanyag, M. (2019). Intersectionality, Transitional Justice, and the Case of Internally Displaced Moro Women in the Philippines. Human Rights Quarterly, 41(2), 399–420.

- Tadem, T. S. E., & Atienza, M. E. L. (2023). The Evolving Empowerment of Local Governments and Promotion of Local Governance in the Philippines: An Overview. In T. S. E. Tadem & M. E. L. Atienza (Eds.), A Better Metro Manila? Towards Responsible Local Governance, Decentralization and Equitable Development (pp. 29–86). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7804-3_2

- te Lintelo, D. J. H., & Hemmersam, P. (2024). Displaceability, placemaking and urban wellbeing. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 7, 100229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2024.100229

- UNICEF. (2023, October 6). Philippines records highest number of child displacements as climate crisis uproots 43.1 million children worldwide. Unicef.Org/Philippines/. https://www.unicef.org/philippines/press-releases/philippines-records-highest-number-child-displacements-climate-crisis-uproots-431

- Yilmaz, S., & Venugopal, V. (2013). Local Government Discretion and Accountability in Philippines. Journal of International Development, 25(2), 227–250. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1687