Reimagining Public Governance Paradigms: Integrating the Nexus of Spiritual Leadership in Africa’s Evolution

Author: Jeremiah Onaolapo

Advisor: Ora-orn Poocharoen

Executive Summary

Africa stands at a critical juncture in its governance evolution. Despite decades of reforms, many African nations continue to struggle with governance systems that are disconnected from their cultural roots and spiritually resonant values. Leadership remains characterized by dominance, mistrust, and disempowerment, particularly among youth. However, there is a growing call for governance models that move beyond bureaucratic efficiency toward wholeness, compassion, and collective well-being.

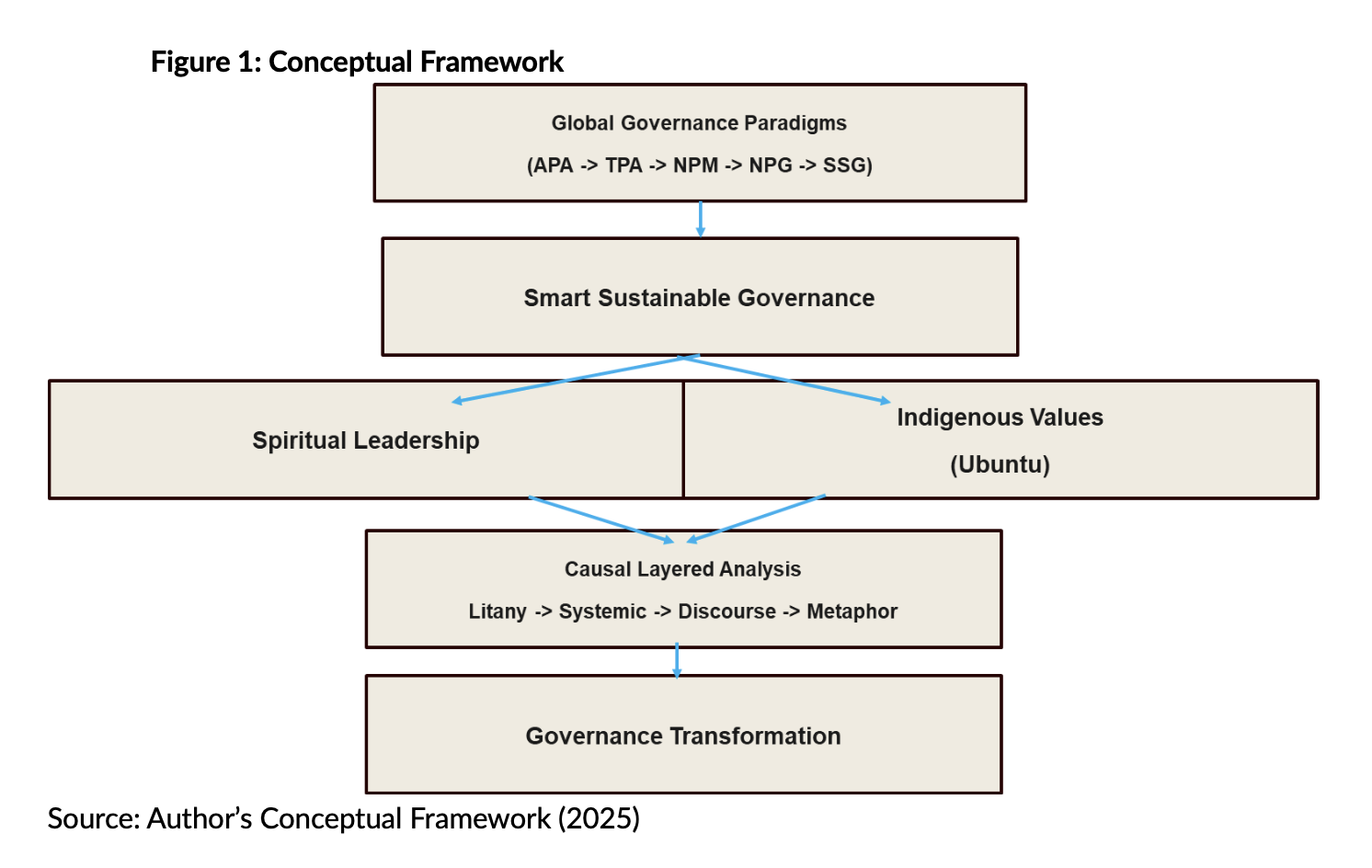

This policy brief proposes the integration of spiritual leadership—rooted in African traditions like Ubuntu and inspired by global approaches like Integral Theory and Smart Sustainable Governance—as a transformative governance paradigm. Drawing on action-based research, a regional survey of 77 respondents across 9 countries, and a participatory workshop with African youth, this brief presents multi-layered insights using Causal Layered Analysis (CLA). It argues that spiritual leadership can offer the moral, emotional, and systemic recalibration needed for Africa’s governance future.

Key recommendations include mainstreaming spiritual leadership training in civil service programs, fostering youth-led governance dialogues grounded in Ubuntu, and embedding cultural-spiritual frameworks into policymaking and public administration curricula.

Table 1: Paradigms evolution in Public Policy and Administration

| Ancient Public Administration (APA) (pre-1950s) | Traditional Public Administration (TPA) (1960s) | New Public Management (NPM) (1980s) | New Public Governance (NPG) (2000s) | Smart Sustainable Governance (SSG) (2020s) | |

| Governance Principles | Only government | Best government | Efficient governance | Good governance | Effective governance |

| To Whom | Commoners | Voters | Customers | Citizens | Public |

| Public Services | Basic provision | Direct provision | Contracted provision | Co-produced provision | Customized provision |

| Role of Government | To rule | To row | To steer | To facilitate | To design |

| Characteristic | Autocratic style | Bureaucratic style | Competitive style | Collaborative style | Constructive style |

| Accountability | Leader | Hierarchy | Market | Network | Multilevel |

| Goal and Focus | Obedience, loyalty-based | Law, rule-based | Indicators, results-based | Relationships, trust-based | Sustainability, justice-based |

| Policy Tools | Command-and-control mechanisms, decrees, edicts, moral persuasion, religious norms, virtue-based appeals, cultural norm reinforcement | Regulation, rules and procedures, public service monopolies, taxation, public sector management, standard-operating procedures | Performance contracts, privatization, outsourcing, cost-benefit analysis, market-based incentives, benchmarking | Public-private partnerships, collaborative agreements, participatory governance, deliberative democracy mechanisms,

citizen juries, co-production |

Spiritual and well-being approaches,

platform provisions, artificial intelligence assisted analysis, ecosystem services, non-human actor engagements. |

Source: Adapted from United Nations Economic and Social Council (2019). Additional policy tools row provided by Ora-orn Poocharoen of the Chiang Mai University School of Public Policy, Thailand (2025).

Problem Statement

The African governance crisis is not merely one of technical failure or corruption—it is a crisis of meaning and identity. For decades, dominant governance models across the continent have been externally imposed, alienating citizens from the state and eroding the moral legitimacy of leadership (Nhema & Zeleza, 2008). The post-independence trajectory inherited and maintained colonial governance logics: hierarchical control, elite centralization, and a neglect of indigenous participatory traditions (Groenemeyer, 2011).

Efforts at administrative reform—such as New Public Management (NPM), and New Public Governance (NPG)—have not substantively shifted governance paradigms. They focus on technical efficiency, managerialism, and procedural reforms, yet neglect the inner lives of leaders and the relational dynamics of communities.

Spiritual leadership addresses these gaps by offering an inside-out approach to governance transformation, rooted in empathy, service, interconnectedness, and meaning-making. As Mbigi (2005) argues, “The African Renaissance must be a spiritual one,” emphasizing a leadership rebirth grounded in African worldviews and ontologies.

Survey respondents and workshop participants voiced consistent concerns over disconnected leadership, a sense of voicelessness, and a loss of collective vision. These findings indicate that reforms focused only on laws or structures are inadequate without deeper value-based and emotional shifts (Survey, 2025; Workshop Transcript, 2025).

Background: African Governance Paradigms

Pre-Colonial Indigenous Governance Systems

Historically, African societies exhibited vibrant participatory governance anchored in communal values, morality, and spiritual cosmologies. Systems such as the Igbo acephalous governance, the Ashanti chieftaincy, and Somali Xeer law show evidence of decentralized, dialogue-based decision-making (Osaghae, 2010). Ubuntu philosophy—“I am because we are”—symbolized relational governance where the leader is a servant of the people, not their ruler (Lutz, 2009).

Colonial and Post-Colonial Transformations

Colonial powers dismantled these systems, replacing them with centralized, hierarchical bureaucracies that served foreign economic interests. Chiefs were co-opted as tax collectors, and governance became synonymous with coercion (Ake, 1996). Post-independence states inherited these bureaucracies and continued the alienation of the populace through “state centrism” and authoritarian development (Hyden, 1983).

Hybrid Governance and Recent Paradigm Efforts

In response, hybrid models have emerged in countries like Ghana and Botswana, integrating traditional authority into state systems (Logan, 2009). The rise of NPM and NPG frameworks introduced efficiency-oriented reforms and co-production initiatives. However, these models are still grounded in Western administrative rationality and do not fully engage Africa’s spiritual-cultural consciousness (Hope, 2012).

Paradigm Adaptations: Smart Sustainable Governance and Integral Approaches

In response to governance gaps, contemporary frameworks such as Smart Sustainable Governance (SSG) and Integral Leadership have emerged globally. SSG calls for systems thinking, digital innovation, inclusion, and ecological awareness (Poocharoen et al., 2019). However, without embedding spiritual and moral capacities, these models risk becoming technocratic. Wilber’s (2000) Integral Theory offers a complementary lens: governance transformation must occur across inner (consciousness, meaning) and outer (systems, behaviors) dimensions. Singh (2021) advances this with the idea of secular spiritual leadership, applicable even in pluralistic public sectors, where leaders can integrate vision, integrity, and compassion into their roles.

Policy Analysis

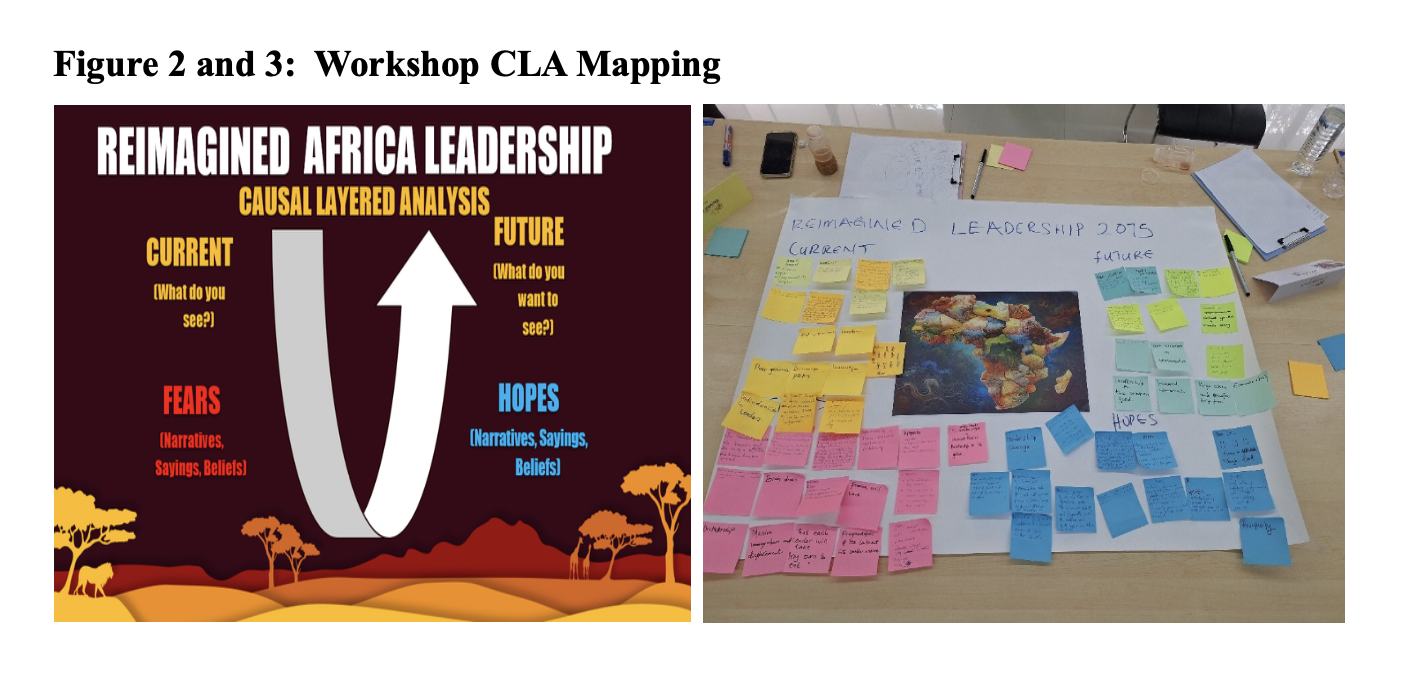

To explore the multi-layered nature of Africa’s governance challenges, this study applied Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) developed by Inayatullah (2004). The Causal Layered Analysis framework is adapted to differentiate between the current dysfunctions and the spiritually grounded aspirations for governance transformation expressed by Africans through an online surveys and experiential workshop. CLA operates on four levels: the Litany (surface symptoms), Systemic (causal institutions), Discourse (deep beliefs), and Myth/Metaphor (core narratives and identities).

1. Online Survey CLA Results

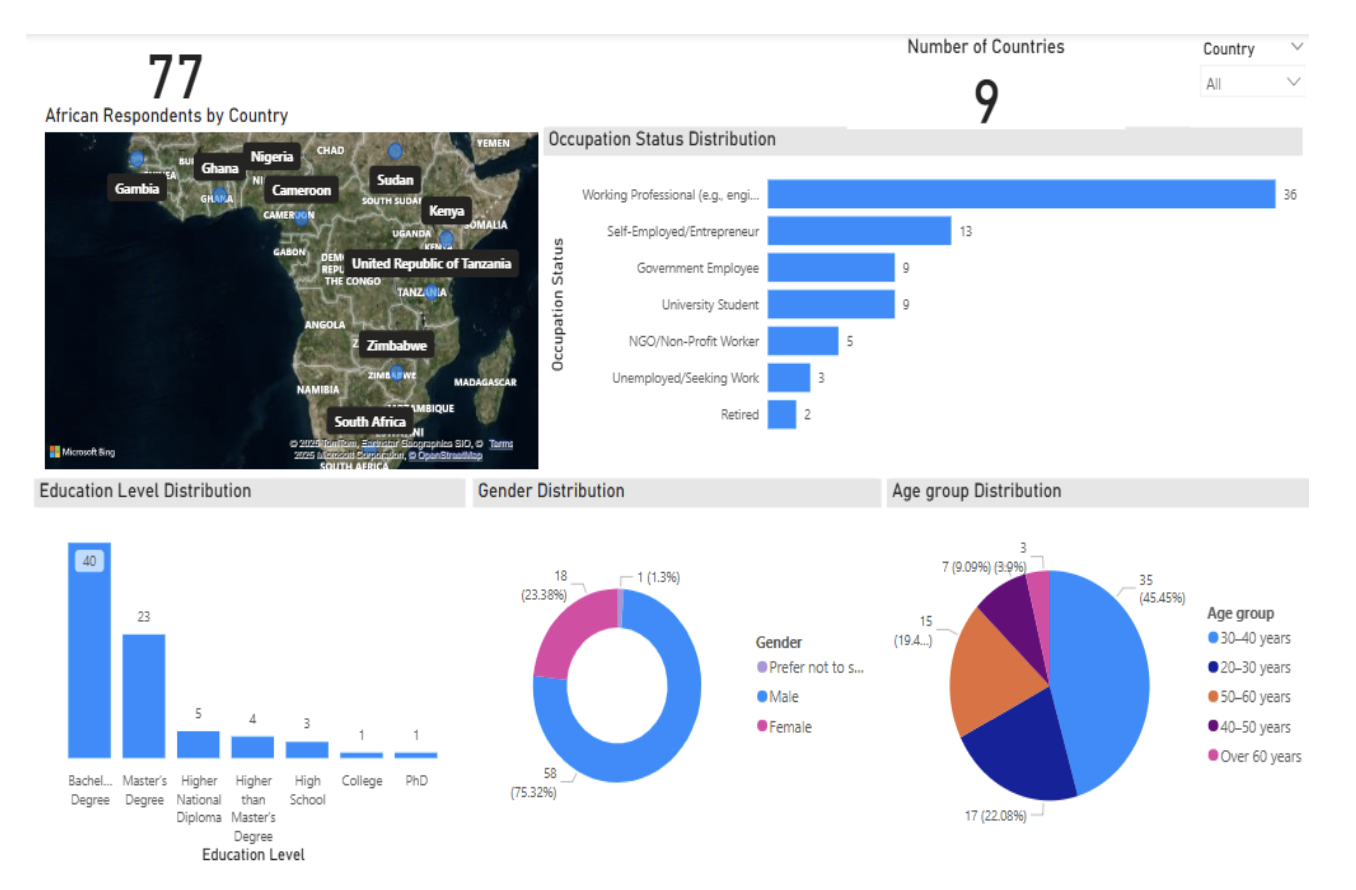

Chart 1: Summary of Respondents’ Demographics

Conducted with 77 Africans from 9 countries, the survey used open-ended questions to explore perceptions and aspirations regarding African governance.

- Litany Level: Common responses highlighted observable issues such as youth unemployment, distrust in leadership, religious/ethnic conflict, and insecurity.

“Youth are absent from the table. Corruption sits in every chair” (Survey, 2024).

- Systemic Level: Respondents identified root causes like over-centralized political systems, lingering colonial legacies, and elite capture of state institutions. The system is perceived as disconnected from citizens’ realities.

- Discourse Level: Dominant narratives include “It’s my turn to eat,” “Citizens are powerless,” and “Politics is for the corrupt.” These beliefs reinforce apathy and disengagement.

- Myth/Metaphor Level: Metaphors such as “Africa is a place of suffering” and “Hopeless and uncertain future” express profound collective trauma. In contrast, reimagined metaphors included “Spiritually awakened citizens,” “Awakening Africa.”

Table 2: CLA Summary from Online Survey

| CLA Layer | Deficit Side (Current Narratives) | Transformative Side (Reimagined Futures) |

| Litany (Observable Problems) | – Distrust – Tribalism and religious conflicts-Policy Inefficiencies – Youth disempowerment – Disconnection between people and themselves |

– Purposeful Nation with Trust – Youth in decision-making positions – Environmental sustainability – Brain gain and innovation hubs – Social inclusion and peace-building |

| Systemic Causes(Structures and Institutions) | – Colonial remnants and authoritarian governance – Policies detached from local values – Centralized power structures – Weak institutional accountability |

– Decentralized governance with local participation – Transparent, merit-based public service – Interconnected policy frameworks rooted in empathy and justice – Technology-enhanced participatory systems |

| Worldview/Discourse(Cultural Frames and Ideologies) | – Greed politics – Citizens lack power or agency – Leadership as domination, not service – Distrust in government and institutions |

– Governance as stewardship and service – Interconnectedness across generations and environments – Belief in collective power for social transformation |

| Myth/Metaphor(Deep Symbols & Emotional Narratives) | – “Leadership as power-hoarding” – “Nation as fragmented and vulnerable” – “Future as hopeless or uncertain” – “Africa as a place of Suffering” |

– “Leadership as nurturing and relational” – “A rising Africa is emerging through a collective awakening across the continent”. – “Spiritually awakened citizens guiding the continent” |

2. Experiential Workshop CLA Findings

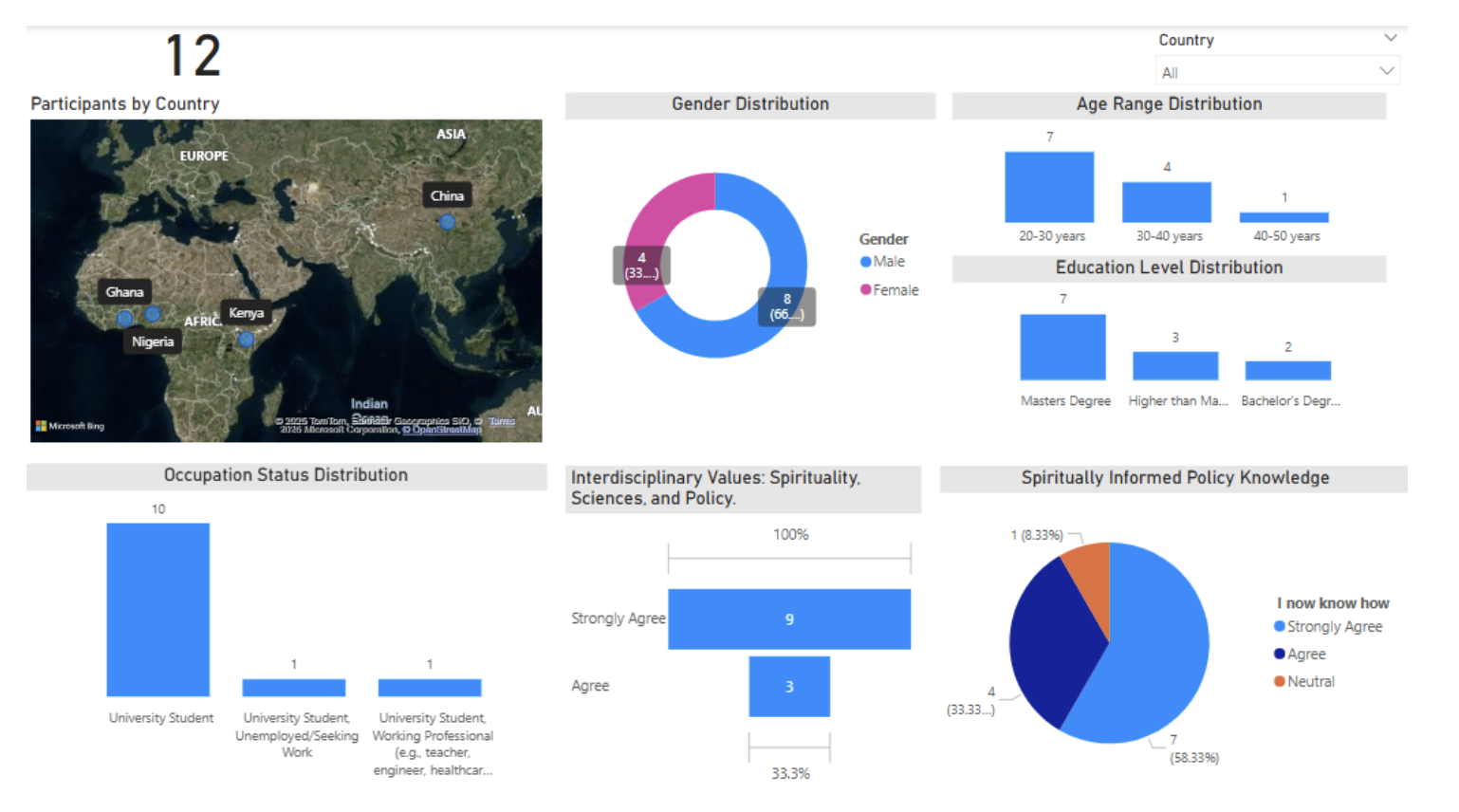

Chart 2: Summary of Workshops Participants’ Demographics

In a 1-day workshop in Chiang Mai, 12 African participants explored governance transformation through embodied activities and CLA exercises.

- Litany Level: Participants described widespread despair, insecurity, and a disconnect between policy and everyday life.

- Systemic Level: Key structural barriers included neo-colonial economic systems, technocratic governance training, and tokenistic youth inclusion. One participant noted, “We are taught leadership from textbooks but never from within.”

- Discourse Level: Pervasive narratives included “Government is not for us,” “Politics is inherited,” and “Leaders don’t listen.” These were challenged by visions of “Leadership as a circle,” “Policy as care,” and “Spirituality as civic duty.”

- Myth/Metaphor Level: Original metaphors such as “A wounded Africa” and “An orphaned future” were reimagined into powerful symbols: Tree of Life rooted in Justice Ubuntu as Homeland and Spiritually Awakened Africa.

Table 3: CLA Summary from Workshop

| CLA Layer | Current Situation (Deficit Side) | Envisioned Future (Transformative Side) |

| Litany (Visible Symptoms) | – Failing economies, injustice, poor governance, insecurity, corrupted leadership – Youth disconnection and despair – Ethno-religious conflict and tribalism |

– Economic vitality, technological progress, and peace, and oneness. – Youth empowerment and inclusion in leadership – Intergenerational visioning |

| Systemic Causes (Structures & Institutions) | – Weak institutions and lack of accountability – Brain drain and lack of youth inclusion – Political structures that reinforce inequality |

– Smart decentralized systems with transparent elections. – Brain gain through return of skilled diaspora – Fair resource distribution and inclusive policy implementation. |

| Worldview / Discourse(Cultural Narratives & Ideologies) | – “It’s my turn to eat” mindset (Politics as elite inheritance) – Citizens feel powerless – Normalization of bad leadership |

– Leadership as public service – Governance as a collective responsibility – Political culture rooted in spiritual values like Ubuntu, integrity, and compassion. |

| Myth / Metaphor (Deep-rooted Beliefs & Collective Imagery) | – “Africa as the broken child” – “Africa is a wounded giant” – “No nature, no future” (climate hopelessness) |

– “Africa as a nurturing womb” – “The tree of life: rooted in justice, flourishing with ethics” (Alkebulan) – “Ubuntu nation: I am because we are” |

3. Emotional and Cognitive Shifts

The Ubuntu circle and nature connection exercises contributed significantly to the cognitive and emotional engagement of the participants. Many shared openly during the dialogue session, reflecting on personal experiences of marginalization, cultural disconnection, and hope for renewal. According to the observation notes, “participants became visibly emotional,” and affirming gestures such as nodding and shared eye contact demonstrated a deepening trust and vulnerability in the group space (Workshop Observation Notes, 2024).

Through activities such as storytelling, journaling, silence, and metaphor exercises, participants began to reconceptualize leadership not simply as power or control but as “presence, rootedness, and relational guidance.” These metaphors reflect a shift in internal narrative, moving from cynicism and critique toward clarity and values-based vision. For example, during the final reflection session, some participants described leadership using natural imagery, including trees, roots, and flowing water—symbols associated with Ubuntu and spiritual connection.

The nature embodiment and connection walk in silence, combined with the leadership journaling activity, helped foster what one participant described as “inner calmness I haven’t felt in years.” This reflective state allowed for a kind of spiritual space and presence that bypassed purely rational discussion and tapped into deeper sources of ethical commitment and imagination.

Overall, these emotional and cognitive shifts are not incidental. They represent the experiential grounding for a new governance paradigm—one based not solely on laws and structures but on relational depth, personal clarity, and community-rooted leadership values.

Stakeholders and Power Dynamics

The transformation toward spiritually grounded governance cannot occur in a vacuum. It requires the active participation and coordination of multiple stakeholders across societal levels. The findings from both the survey and workshop identify several key stakeholder groups whose roles must be reimagined, challenged, and empowered.

Youth emerge as the most vocal, visionary, and yet most structurally excluded group. Their dissatisfaction with current governance is matched by a readiness to engage, lead, and innovate. However, youth often remain tokenized in policy dialogues. A shift must occur where youth are no longer seen as beneficiaries but as co-creators of governance. As one workshop participant asserted:

“We don’t just want seats at the table—we want to codesign the table.”

Civil servants and public officials, on the other hand, are constrained by bureaucratic cultures that prioritize compliance over creativity. Many lack the training to engage citizens empathically or to make decisions that reflect relational and moral values. Leadership development programs in the civil service must therefore integrate spiritual intelligence, systems thinking, and ethics of care—moving from management training to consciousness-based governance education.

Traditional leaders and cultural custodians remain critical. Their spiritual legitimacy, community proximity, and moral standing provide a unique channel for embedding spiritual leadership in governance. In countries where these institutions have been co-opted or delegitimized, efforts must be made to revive and redefine their governance roles in ways that support rather than undermine democratic values.

Educators and religious institutions also play a crucial role. Spirituality in this policy brief is not about religiosity—it is about inner development, moral vision, and social purpose. As such, partnerships between governance bodies, schools, and faith-based organizations can build capacity for value-based leadership, storytelling, and civic formation.

Finally, policy institutions and donors need to acknowledge the limitations of purely technical interventions. Programs must be designed with cultural humility, allowing for endogenous, spiritually rooted governance innovations to emerge. Rather than imposing policy templates, external actors should act as facilitators of local wisdom, creating space for relational, narrative-based policymaking. Moreover, donors and external institutions must decolonize their governance models and support endogenous, value-based governance innovations (Singh & Bhatnagar, 2023). The governance shift proposed here demands a realignment of power, responsibility, and meaning across sectors, with spiritual leadership serving as the moral and strategic anchor for such reconfigurations.

Policy Recommendations

Creating Space for Spiritually-Grounded Leadership

Rather than introducing another bureaucratic checklist, this section invites for the revitalization of inner leadership values in Africa’s public and civic spaces. The policy vision emphasizes values-based leadership formation embedded in national training ecosystems, not as peripheral programs, but as central to transformative governance.

-

Integrate Ubuntu-Based Spiritual Leadership into Civil Service and Leadership Training Institutions

Training programs must be reimagined not merely as technical or competency-based initiatives but as intentional spaces for inner transformation. Civil service academies, leadership colleges, and youth fellowships across Africa should incorporate Ubuntu-based practices, including storytelling circles, spiritual ecology, nature-based rituals, reflective journaling, and intergenerational dialogues. These modules should be designed and facilitated in partnership with African scholars, spiritual practitioners, and Ubuntu-informed educators to ensure they are culturally rooted and experientially impactful. Pilot programs can begin in selected national training institutions, where the focus shifts from simply transferring knowledge to fostering emotional intelligence, moral clarity, and spiritual presence in leadership.

-

Scale the Workshop Model as a Public Leadership Prototype

The workshop model first implemented in Chiang Mai should be adapted and replicated across African contexts through localized leadership labs embedded within universities, ministries, and youth-focused organizations. These labs must provide participants with culturally relevant metaphors, stories, and practices, delivered in the languages and symbolic frameworks of their regions. Designed to promote spiritual safety and trust, the sessions must go beyond intellectual dialogue to include poetic expression, contemplative silence, collective reflection, and embodied spiritual exercises. By allowing space for emergence rather than enforcing rigid outcomes, this model offers a dynamic template for cultivating leaders who lead with presence and deep relational awareness.

-

Establish a Fellowship of Ubuntu Spiritual Leaders-in-Training

A pan-African fellowship should be established to support youth who demonstrate a strong capacity for spiritual presence, relational leadership, and community care. The fellowship would include immersive Ubuntu-based retreats followed by grassroots service placements rooted in collective governance and healing justice. Fellows would engage in narrative policy co-creation, host civic storytelling circles, and reflect on their leadership journeys through art, silence, and service. The selection process should emphasize lived values and integrity over academic qualifications, and mentorship would be offered by elders, artists, spiritual thinkers, and local governance innovators. This model is not about producing more charismatic leaders; it is about nurturing rooted and accountable ones.

-

Create Reflective Leadership Spaces Inside Government

Public institutions and ministries should institutionalize “Reflection Circles”—spaces where civil servants regularly gather to explore purpose, empathy, and connection in their governance work. These spaces are not for debate or performance evaluation, but for human reconnection through storytelling, silence, and collective presence. The circles can begin in select ministries or agencies, facilitated by trained peers and spiritual practitioners, and gradually expand as trust and demand grow. The impact should be documented not through traditional KPIs, but through testimonies, shifts in interpersonal trust, and increased moral clarity in public decision-making. These spaces can serve as living reminders that governance is not only about policies—it is about people.

Implementation Roadmap

| Phase | Timeframe | Key Activities |

| Initiation | Immediate (0–1 year) | Develop spiritual leadership modules; form taskforces; pilot Reflection Circles. |

| Development | Short-Term (1–2 years) | Launch certification program; design fellowship framework; train facilitators. |

| Expansion | Medium-Term (2–3 years) | Scale workshops; launch multi-country evaluation systems |

| Institutionalization | Long-Term (3–5 years) | Embed modules and indicators into national systems; integrate MEL systems |

Anticipated Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

| Challenge | Mitigation Strategy |

| Resistance to spiritual framing in public institutions | Recast spiritual leadership in secular terms as a relational and consciousness-based tool |

| Institutional inertia in leadership education | Engage reform champions and build change through cross-sector partnerships |

| Risk of youth tokenism | Establish co-creation models and participatory design processes |

| Resource limitations | Leverage regional partnerships and non-traditional funders (e.g., AUDA, UNDP) |

| Monitoring complexity for spiritual transformation | Apply mixed-method tools, combining stories, surveys, and reflective logs |

Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL)

A spiritually sensitive MEL framework requires both quantitative metrics and qualitative stories of transformation. Learning loops should be iterative and embedded in civic reviews.

Key Components:

- Indicators: Narrative shifts, public trust levels, workshop participation, Ubuntu-based service impact

- Feedback: Post-training assessments, fellowship impact reports, community reflection logs

- Methods: Mixed methods—quantitative + reflective storytelling, journaling, and narratives

- Learning Loops: Annual MEL reviews embedded into AU, APRM, and national governance review cycles

- MEL Actors: AU Public Service Division, National Planning Departments, Research Universities

Expected Outcomes

- Institutionalized practice of spiritually informed leadership grounded in Ubuntu values

- Improved public trust and reduced leadership alienation

- Stronger holistic legitimacy rooted in culture, ecology, and spirituality

- Accessible leadership formation spaces beyond formal education

- Continental benchmarking tools to track spiritual transformation in governance

These policy recommendations offer a pathway to embed soul, ethics, and collective care into African governance. By building on indigenous wisdom, empirical evidence, and globally resonant leadership principles, Africa can shape governance systems that are both effective and spiritually grounded—where service, not dominance, defines leadership.

Conclusion

This study explored the integration of spiritual leadership into African governance frameworks, positioning it as a transformative approach within the Smart Sustainable Governance (SSG) paradigm. Drawing from Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), African indigenous philosophies such as Ubuntu, and empirical insights from both a participatory workshop and a continent-wide survey, the research has demonstrated that spiritual leadership—rooted in compassion, moral purpose, and relational accountability—offers a viable alternative to governance models currently marked by mistrust, technocracy, and disconnection.

The findings underscore that spiritual leadership is not merely an ethical supplement but a structurally and culturally relevant governance tool. It addresses the deeper crises of legitimacy, identity, and meaning that persist in postcolonial African administrative systems. Through the lived experiences and aspirations of African youth and reflective practitioners, this study reveals a collective desire to move toward governance grounded in care, inclusion, and ancestral wisdom.

References

- Ake, C. (1996). The unique case of African democracy. International Affairs, 69(2), 239–244.

- Ekeh, P. P. (1975). Colonialism and the two publics in Africa: A theoretical statement. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 17(1), 91–112.

- Hope, K. R. (2012). The new public management: Context and practice in Africa. International Public Management Journal, 4(2), 119–134.

- Hyden, G. (1983). No shortcuts to progress: African development management in perspective. University of California Press.

- Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method. Futures, 30(8), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X

- Logan, C. (2009). Selected chiefs, elected councillors and hybrid democrats: Popular perspectives on the co-existence of democracy and traditional authority. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 47(1), 101–128.

- Lutz, D. W. (2009). African Ubuntu philosophy and global management. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(Suppl. 3), 313–328.

- Mbigi, L. (2005). The spirit of African leadership. Knowledge Resources.

- Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton University Press.

- Nhema, A. G., & Zeleza, P. T. (2008). The roots of African conflicts: The causes and costs. Ohio University Press.

- Osaghae, E. E. (2010). The role of traditional institutions in political change and development. CODESRIA.

- Poocharoen, O., D’Achon, E., Mendez, J., & Mendjana, L. (2019). Enhancing the capacity of the public sector in a fast-changing world for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations Economic and Social Council (E/C.16/2019/2).

- Poocharoen, O. (2024). Paradigms of public policy and governance in Asia: From ancient administration to smart sustainable futures. In Handbook on Asian Public Administration (pp. 1–45). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Reave, L. (2005). Spiritual values and practices related to leadership effectiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(5), 655–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.003

- Singh, N. (2021). Secular spiritual leadership for public policy: Integrating values, ethics, and governance transformation. Emerald Publishing.

- Singh, N., & Bhatnagar, D. (2023). Applied spirituality and sustainable development policy. Emerald Publishing.

- Wilber, K. (2000). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Shambhala Publications.

- Workshop Observation Notes. (2024). Internal workshop materials compiled by the author from participatory governance workshop, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Download full article: Click