Bridging Divides, Building Futures: Feasibility of a Malaysia-Supported Private School Model in Thailand’s Deep South

Author: Kusselin Yuthasax Prak Chuap

Advisor: Ora-orn Poocharoen

Problem Statement

The education system in Thailand’s Deep South is embedded in a complex sociopolitical context. A history of state-led centralization and cultural assimilation has fostered deep mistrust, particularly among the Malay Muslim majority, who often perceive the national curriculum as insensitive to their religious and cultural identity (Tuansiri, Pathan, & Koma, 2018). Although various school types exist, including government schools, private Islamic schools, traditional pondok, general private schools, and tadika, none fully address the combined needs of identity preservation, academic advancement, and intergroup coexistence. Public schools are often seen as poorly adapted to local cultural and linguistic contexts (Tuntivivat, 2022). Private Islamic schools offer both religious and secular subjects, but the quality and emphasis on academic instruction varies widely across institutions. In many cases, religious education remains the core focus, with academic components added mainly to meet policy requirements, as noted during fieldwork with educators in Pattani (2025). As a result, children from different communities rarely learn together. This separation is not driven by school preference alone. Demographic shifts, including the outmigration of Thai Buddhist families from rural areas due to security concerns, have also contributed to schools being composed mostly of one cultural or religious group (Tuntivivat, 2022). These dynamics make it difficult to foster integration through education alone. This fragmentation not only reflects but also reinforces societal division. It undermines national unity, deepens long-term alienation, and constrains the transformative potential of education as a peacebuilding tool. There is an urgent need for a school model that is inclusive, culturally grounded, and academically competitive. This policy brief proposes a Malaysia-supported “Thai–Malay School” model as a pilot private school initiative.

Policy Analysis

1. Stakeholder Perspectives: Hopes and Fears

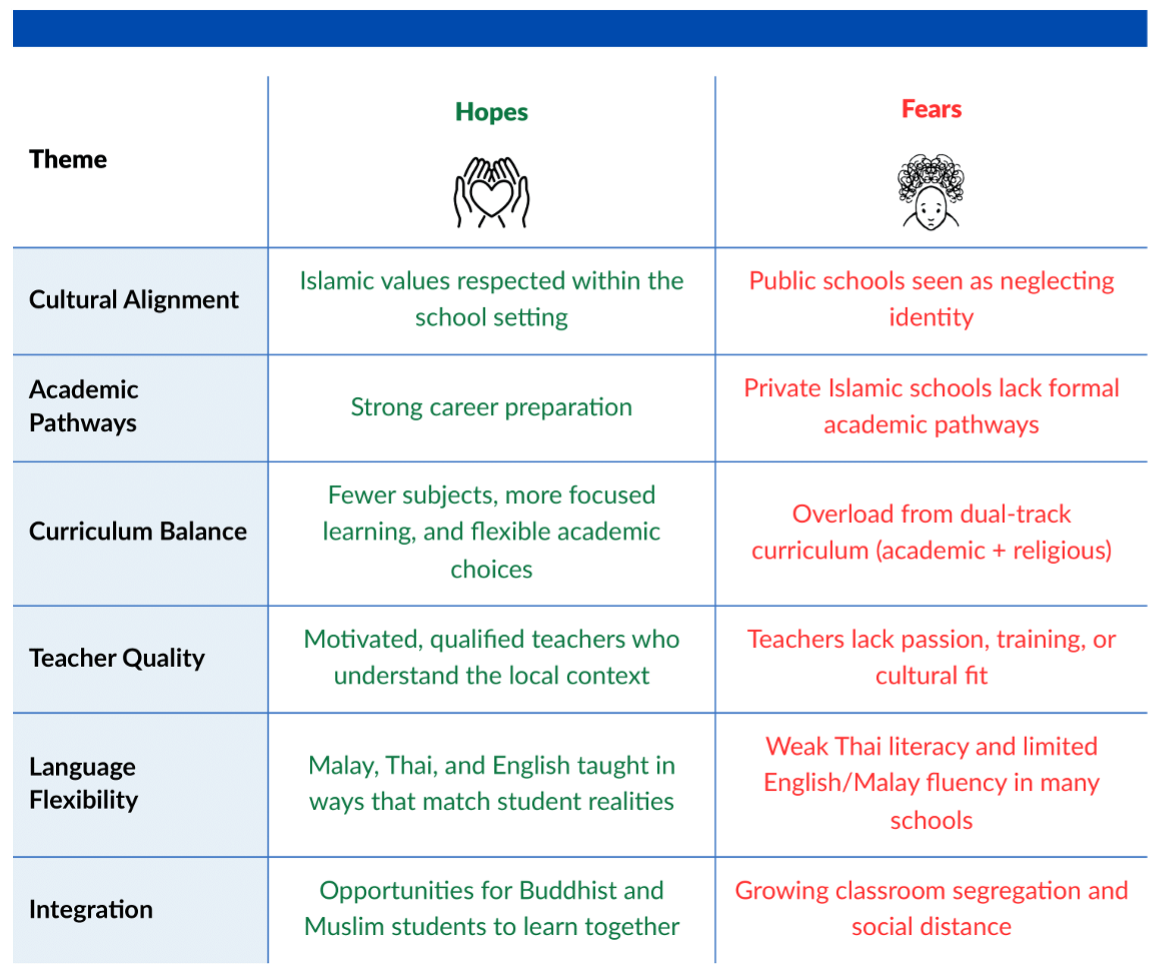

Semi-structured interviews with 10 stakeholders in Pattani, conducted between 28 April and 4 May 2025, highlighted both aspirations and deep concerns. Parents, educators, local youths, and school owners/leaders converged on several key themes:

Table 1: Key themes based on interviews with educators, parents, local youths,

and school leaders in Pattani, Yala, and Nathawi (2025)

These themes illustrate the multidimensional nature of educational challenges in the Deep South. While stakeholders expressed strong hopes for schools that integrate cultural identity, language flexibility, and academic readiness, they also voiced concerns about curriculum overload, weak foundational skills in Thai, and growing intergroup segregation. The contrast between hopes and fears highlights not just dissatisfaction with current school types, but a deep yearning for a model that can bridge these divides.

2. Gap in Existing Models

2.1 Trust, Identity, and Parental Preferences

In the Deep South, cultural and religious identity is central to school preference, especially for Malay Muslim families. Government-supported private Islamic schools and fully private Islamic institutions are often trusted to reflect local values (Assalihee et al., 2024). These schools often combine Islamic subjects with the Thai curriculum, though some institutions tend to prioritize religious education more heavily. For many parents, this creates a sense of alignment with their linguistic and faith-based worldview.

However, according to interviews conducted in Pattani (2025), some private Islamic schools tend to emphasize Arabic and Islamic studies more than Thai or English. This limits students’ ability to engage with broader Thai society or pursue diverse higher education pathways. In contrast, national schools are widely perceived as agents of assimilation (Tuntivivat, 2023), and despite offering some Islamic studies or Malay language tracks, they often struggle to build trust with local communities. As a result, public education is seen as religiously and culturally alien, even if teachers themselves are locally recruited. Consequently, public education is often perceived as culturally disconnected, reinforcing distrust and shaping parental preferences away from national schools.

2.2 Curriculum Strain & Academic Trade-offs

Thailand’s education system, especially in the Deep South, has tried to accommodate diversity. However, it often does so through additive inclusion rather than structural transformation. In recent years, attempts to appear more inclusive have led many schools, especially government and private Islamic schools to add identity-based subjects such as Jawi, Malay language, or Islamic studies on top of the national core. One key driver of this trend is the Inclusive Education Zone (IEZ) program, which provides per-student funding to both public and private schools that participate (Royal Thai Government Gazette, 2019). In practice, this has created competition among schools to appear culturally responsive, often by expanding subject offerings to attract more students and secure continued funding. Despite well-meaning efforts to reflect community preferences, the practice of continually adding identity-based subjects on top of the national core has resulted in curriculum bloat. Some primary schools now teach as many as 11 to 13 subjects per week as noted during fieldwork. Teachers are overstretched, students are exhausted, and the intended cultural respect risks becoming an academic burden rather than a meaningful reform.

General private schools in Pattani cater to families seeking higher academic standards and broader subject offerings. According to the interview with some private school owners, these schools attract middle- and upper-income Malay Muslim families who are drawn to their academic quality and the broader exposure they offer. Religious education is often arranged separately at home or in community settings. Many students transfer to Islamic schools after graduation, suggesting these models serve a narrow demographic and do not meet the broader community’s needs. Despite their differences, all current models fail to offer a unified solution—none combine a quality education, cultural trust, and curriculum clarity in a way that meets the region’s long-term needs.

2.3 From Separation to Shared Space: Why a New Public Model Matters

Over the past two decades, more and more families in Thailand’s Deep South have turned to private Islamic schools. This shift is understandable. These schools are seen as culturally safe, religiously aligned, and often more responsive to local needs. In many cases, they are trusted more than public schools, not because they are perfect, but because they feel closer to the values and identities of the community.

Still, the long-term effects of this trend deserve attention. When children grow up learning only among peers who share the same background, opportunities for mutual understanding become limited. Although national schools are open to all, many have become almost entirely Malay Muslim in practice. This is partly due to demographic changes, but also reflects deep patterns of school choice and community trust. Over time, this creates a quiet form of separation, where students from different groups rarely share the same learning space.

A Thai-Buddhist teacher working in a 100% Muslim school shared her concern about students’ preparedness for navigating mainstream Thai society:

- “My students are always polite, they greet me with a “salam” and they are respectful. But I’m worried — what happens when they grow up and go out into broader Thai society? They don’t know how to “wai”. Some people might see them as rude, even if that’s not their intention.”

On the other hand, A Malay-Muslim school principal at a national school observed that even within local communities, cultural assumptions can deepen division:

- “Sometimes we think we understand each other, but we actually don’t. I once got asked sarcastically ‘Going to pray again?’. I also know some people feel the support given to Malay-Muslims is too much. I just feel that if we really understood each other’s culture, we wouldn’t have these tensions.”

These are not criticisms of private Islamic schools, nor of families who choose them. Rather, they reveal a deeper challenge. If public education continues to fall short in building trust and cultural alignment, then separation will remain the default. That is why the government must take an active role in offering a better alternative—one that families can believe in.

3. Why Malaysia?

Malaysia offers a regionally grounded yet forward-looking model for communities in Thailand’s Deep South. The country shares long-standing linguistic, religious, and cultural ties with the region’s Malay-Muslim population, and its education system is frequently cited as a model for integrating Islamic values with modern, globally relevant academic standards (Abdul Hamid, 2017; Kadir et al., 2022).

One of the clearest examples is Malaysia’s support for vernacular schools. The SJKC (Chinese) and SJKT (Tamil) models demonstrate how identity-based education can operate within a national framework without compromising social cohesion. These schools receive government funding, follow the national curriculum, and still require all students to study Bahasa Melayu as a compulsory subject. This ensures national unity through language, while preserving the right to mother-tongue instruction. The result is a system that promotes both inclusion and trust. A notable case in early 2024 illustrates this growing public trust. At a Chinese-medium school (SJKC) in Negeri Sembilan, an entire Standard 1 class was composed entirely of Malay students. This reflects how vernacular schools, when viewed as inclusive and academically strong, can attract families across ethnic lines. The decision was based not on ethnic identity, but on perceived quality and trust (World of Buzz, 2024). It suggests that when education models are community-rooted and performance-driven, they can maintain cultural identity while fostering broader public confidence.

This policy brief does not propose directly replicating the SJKC model or importing Malaysia’s school structure. Rather, it draws inspiration from the principle behind these schools: that identity-affirming education, when supported by the state and delivered with quality, can foster both belonging and national unity. In this spirit, we propose a new school model that integrates Thai, Malay, and English as equal pillars. Thai supports national integration and legal literacy, Malay fosters cultural trust and local belonging, and English prepares students for international opportunity. Should political conditions allow, the model could benefit from technical support or symbolic partnership from Malaysia, particularly in teacher training, curriculum development, or soft diplomacy. However, the core vision is for Thailand to own and localize this initiative as a national investment in inclusive education.

A Malay-Muslim principal at a rural national school in Pattani said:

- “For many Malay-Muslim families, identity matters more than anything. Arab-funded schools are trusted not just because of resources, but because of their religious image. If a Malaysia-supported school is introduced, it could attract real interest — not just as a new product, but because people here see Malaysia as both Islamic and academically strong. Families today want children who are smart in all aspects — religious, yes, but also professionally capable, like doctors or technical experts.”

This sentiment reflects a broader desire for models that affirm cultural values while expanding academic and career possibilities. In contrast, existing school options in the Deep South are often perceived as limited in scope and lacking the innovation needed to respond to evolving community needs.

Note: Thailand and Malaysia have a long history of education cooperation, including a prior MoU signed on August 21, 2007, that supported teacher exchanges and joint curriculum development (see archived copy here).

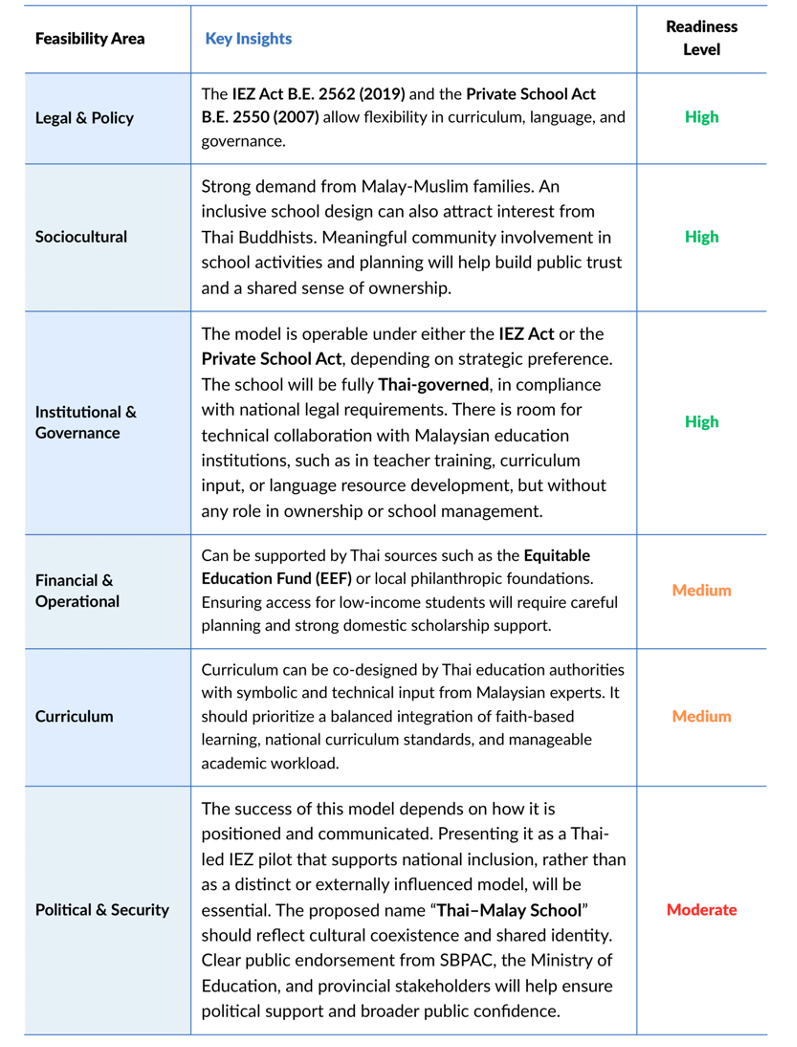

4. Feasibility Summary

The proposed school model was assessed across six feasibility dimensions. A summary is presented below.

Table 2: Feasibility assessment of the Malaysia-supported School model.

Note: Readiness levels are based on qualitative assessments of legal feasibility, institutional support, and political sensitivity as of this writing.

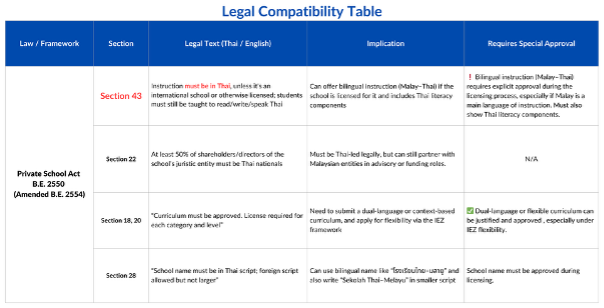

Legal-Policy Alignment Note:

A detailed legal review confirms that Section 43 of the Private School Act (B.E. 2550, amended B.E. 2554) presents a clear limitation by mandating Thai as the medium of instruction. However, the Innovation Education Zone (IEZ) Act (B.E. 2562) offers a legally valid pathway for experimentation (see tables 3 and 4).

Table 3: Legal Compatibility – Private School Act (B.E. 2550, Amended B.E. 2554)

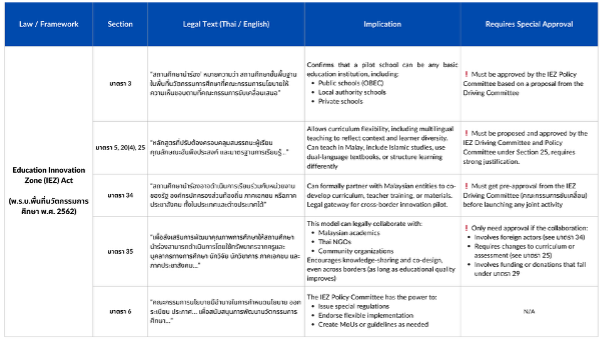

Core provisions under the IEZ Act (Sections 3, 5, 20(4), and 25) provide a legal basis for this model. Section 3 confirms that private schools can be registered as pilot schools (สถานศึกษานำร่อง) within the Innovation Education Zone framework. Sections 5 and 20(4)allow for curriculum adaptation and contextual learning innovation, while Section 25 enables pilot schools to propose adjustments to instructional language, delivery method, and learning materials.

This legal flexibility creates room to introduce Malay as the primary medium of instruction, alongside Thai language support. The model can also propose bilingual learning materials and flexible internal assessments, aligning with both national standards and the local educational context.

Recommendations

To translate community hopes into concrete change, this brief proposes four interconnected policy actions, designed to be both practical and scalable. These recommendations are drawn from stakeholder interviews, comparative education insights, and existing legal frameworks in Thailand.

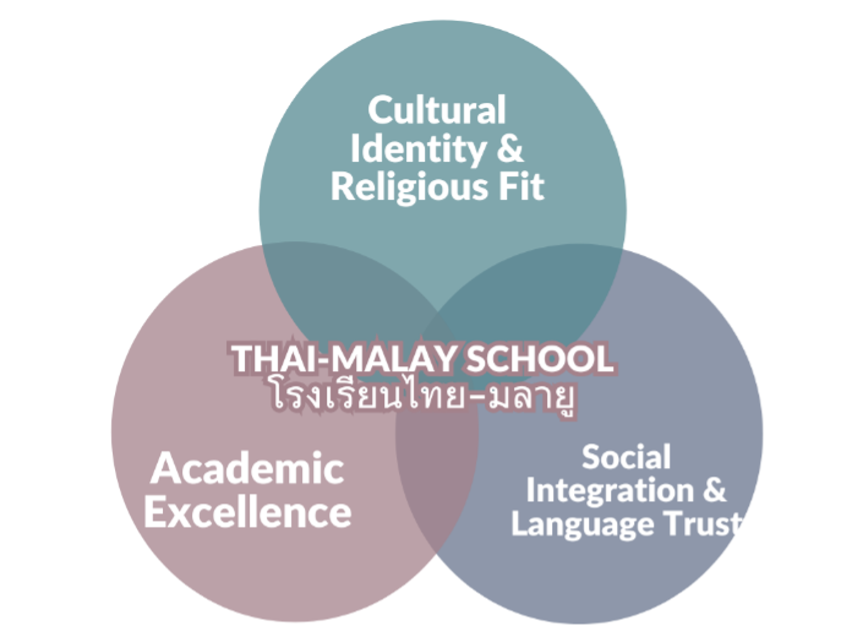

I. Pilot a Thai–Malay School in Pattani with Regional Support

This brief recommends piloting a “Thai–Malay School” (โรงเรียนไทย–มลายู) in Pattani to fill the gap in current options, structured as a government-recognized private school that combines academic quality with cultural and linguistic trust. Although the region currently offers national, general private, and Islamic private schools, none explicitly affirm Malay-Muslim identity while delivering academic content through the Malay language. The proposed model positions Malay as a core language of instruction, not just a subject. Key subjects such as Mathematics and Science will be taught using bilingual content in Malay and Thai, supporting both comprehension and integration. Thai will remain a required core subject, in full alignment with national education policy. English will be offered as a standalone subject, equipping students with communication skills for future academic and professional opportunities.

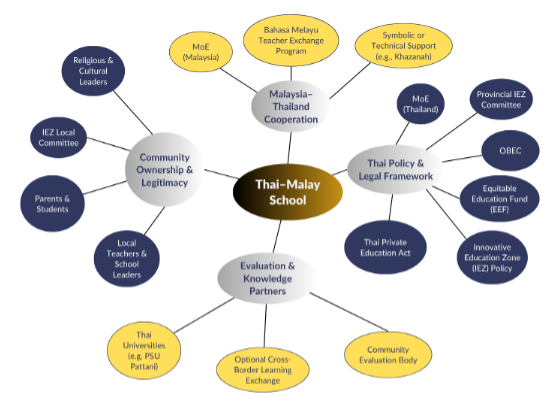

Operating under the Innovation in Education Zone (IEZ) framework, the school would use legal flexibility to design a bilingual curriculum that includes Malay-medium instruction and flexible learning materials and assessments. The initiative would be Thai-led, but may benefit from symbolic or technical or collaboration with regional partners such as Khazanah Nasional Berhad or Malaysian education institutions, reflecting Malaysia’s broader commitment to education diplomacy. This pilot could serve as a national demonstration of how localized, identity-affirming innovation can support long-term solutions for educational access and peacebuilding in the Deep South.

Figure 1. Core Design Principles of the Thai–Malay School Model: Balancing Identity, Opportunity, and Integration

II. Develop a Dual-Track Curriculum Balancing Religious and Academic Needs

To address the curriculum overload found in many current schools, the Thai–Malay School model will adopt a streamlined dual-track approach. This structure offers flexibility without overwhelming students, while respecting both academic goals and religious commitments. The curriculum will accommodate the diverse needs of families in the Deep South by allowing parents and students to choose between two tracks with varying levels of Islamic education, all within a shared learning environment.

The first track follows a general academic pathway that includes modules on Islamic values. Non-Muslim students, if enrolled, may receive moral and civic education tailored to their backgrounds. This track supports ethical development while emphasizing core STEM and language skills, such as scientific thinking, mathematics, multilingual literacy, and digital fluency. The second track offers a specialized Islamic pathway for students seeking deeper religious instruction. Subjects include Jawi, Arabic, Quran memorization (tahfiz), Fiqh, and Hadith, with learning trajectories aligned to Islamic teaching certifications and pathways into religious leadership or advanced study.

Both tracks will share selected classes and participate in joint projects to foster mutual respect, collaboration, and soft skill development. Parents would choose a track at enrollment, but the school should allow flexible switching to support academic fit and student well-being. This inclusive model which balances identity, student choice, and academic readiness could offer meaningful options without requiring families to choose between faith and future opportunity.

III. Establish a Community-Led Evaluation and Scale-Up Mechanism

To ensure that the Thai–Malay School pilot becomes a sustainable and context-responsive model, the Ministry of Education, in collaboration with the Provincial Innovative Education Zone (IEZ) Committee, should establish a community-led evaluation and learning mechanism from the outset. This mechanism should go beyond traditional top-down monitoring by actively involving local stakeholders, including parents, teachers, school leaders, religious figures, and students. Together, they can define success indicators and monitor progress based on local priorities. Evaluation criteria should include not only academic performance but also levels of trust, cultural responsiveness, language accessibility, and student well-being. Practical tools may include teacher journals, student feedback forms, community meetings, and classroom observations.

The evaluation process should also generate clear documentation on what works and where adjustments are needed. These findings will help inform whether and how the model should be expanded to other provinces. By embedding participatory evaluation from the beginning, the pilot will foster transparency, strengthen local ownership, and ensure that any future expansion is based on real evidence and continuous improvement.

IV. Institutionalize Thai–Malaysia Educational Cooperation Through MoUs

Long-term sustainability requires clear structures and shared responsibility. To this end, the Thai and Malaysian governments should establish a dedicated Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) focused specifically on supporting the proposed Thai–Malay School model. This MoU should outline clear commitments from both parties to co-develop and sustain this initiative under the Innovative Education Zone framework. Key areas for collaboration should include:

- Teacher exchange programs, particularly in Bahasa Melayu and Islamic education, to strengthen classroom capacity and cross-border teaching expertise.

- Co-development of curriculum, components, especially in Islamic studies and Malay-medium delivery, drawing on Thai standards and Malaysian experience.

- Joint creation of bilingual teaching resources and culturally responsive classroom tools to support inclusive, context-sensitive instruction.

- Professional learning exchanges between Thai and Malaysian educators to build mutual understanding, share practices, and inform school improvement over time.

This agreement would build on the renewed spirit of bilateral cooperation emphasized during the 7th Annual Consultation between the two Prime Ministers in December 2024, where both countries committed to strengthening educational ties (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, 2024). By institutionalizing this partnership through a formal MoU, policymakers can assure local stakeholders that the Thai–Malay School model is not a short-term experiment, but part of a serious, government-backed effort to address long-standing educational and cultural tensions. The model may also inform future ASEAN-wide education partnerships in diverse or conflict-prone areas.

Figure 2. Thai–Malay Pilot School Stakeholder Ecosystem and Policy Alignment Pathways

Conclusion: Education as a Bridge, Not a Barrier

In Thailand’s Deep South, the education system continues to reflect deeper political and identity struggles. The region does not lack schools, but it lacks schools that genuinely unify communities or prepare youth for a shared and peaceful future. Though family school choices are a factor, the separation seen today is equally shaped by demographic shifts and broader trust issues in state education. A model that promotes shared spaces, rather than segmented schooling, is essential to reversing these long-standing divides.

A Malaysia-supported Thai-Malay school model, if co-designed with local stakeholders, has the potential to be both trusted and transformative. If successful, this model could open new pathways for peacebuilding, educational equity, and intercommunal coexistence. It is not intended to replace existing systems but to offer an alternative that respects cultural identity while unlocking academic and professional potential.

By blending Islamic values with bilingual fluency, academic quality, and institutional inclusion, the proposed initiative can help rebuild community trust, reduce long-standing divisions, and serve as a working model for education-led reconciliation. Beyond curriculum and access, the Thai–Malay School model also represents something deeper. Based on insights gathered during this study, its very existence would send a powerful signal that the Thai state sees Malay-Muslim communities not only as Muslims, but as Malays. For many, this would mark the first time their identity is formally acknowledged within the national education system. The window of opportunity is open. The time to pilot such a model is now, before another generation grows up further apart.

References

[1] Abdul Hamid, A. F. (2017). Islamic education in Malaysia. In E. Aslan (Ed.), Handbook of Islamic Education (pp. 1–20). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53620-0_27-1

[2] Assalihee, M., Bakoh, N., Boonsuk, Y., & Songmuang, J. (2024). Transforming Islamic education through lesson study (LS): A classroom-based approach to professional development in Southern Thailand. Education Sciences, 14(9), 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14091029 .

[3] Kadir, N. A. A., Rahman, M. F. A., Ayub, M. S., Razak, M. I. A., Noor, A. F. M., & Shukor, K. A. (2022). The development of Islamic education in the Malay world: Highlighting the experience in Malaysia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 12(10), 1218–1231. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i10/15300

[4] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand. (2024, December). Joint press statement on the 7th Annual Consultation between the Prime Ministers of Thailand and Malaysia. https://www.mfa.go.th/en/content/joint-press-statement-pm-malaysia-thailand

[5] Royal Thai Government Gazette. (2019). ประกาศกระทรวงศึกษาธิการ เรื่อง เขตพื้นที่นวัตกรรมการศึกษา [Announcement from the Ministry of Education: Innovative Education Zone Policy]. http://www.ratchakitcha.soc.go.th/DATA/PDF/2562/A/056/T_0102.PDF

[6] Tuansiri, E., Pathan, D., & Koma, A. (2018). Understanding anti-Islam sentiment in Thailand. Peace Resource Collaborative. https://peaceresourcecollaborative.org/en/deep-south/understanding-anti-islam-sentiment-in-thailand

[7] Tuntivivat, S. (2022). Psychosocial impact on public school enrollment in armed conflict areas of southern Thailand. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 11(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2022.2075996

[8] World of Buzz. (2024, January 6). Chinese school in Negeri Sembilan has 100% Malay students enrolling in Standard 1 class. https://worldofbuzz.com/chinese-school-in-negeri-sembilan-has-100-malay-students-enrolling-in-standard-1-class/

Download full article: Click