China’s Relations with Myanmar Military After the Coup: What We Know and What We Don’t

Author: Wai Moe

Workers put up flags a day before Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in Naypyitaw on Jan 16, 2020. (Photo: Reuters)

Abstract

This paper examines Myanmar’s complex political landscape and its evolving relationship with China. The analysis is based on interviews with key stakeholders, including military officers, diplomats, and business leaders. It discusses China’s historical role, strategic interests, and shifting policies toward Myanmar, particularly in the wake of the 2021 coup. The study highlights China’s diplomatic maneuvers, economic interventions, and responses to Myanmar’s internal conflicts. Additionally, it explores Myanmar’s balancing act between regional powers and the geopolitical implications of China’s increasing influence. Understanding these dynamics is critical for assessing regional stability and geopolitical shifts in Southeast Asia.

Introduction

Myanmar’s politics have been complicated since the Southeast Asian nation gained independence from the British in 1948.[1] Since then, Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) has been in civil war and the Myanmar armed forces (or the Tatmadaw) have been a key player in politics. The Southeast Asian nation was under military dictatorship directly or through proxy parties from 1962 to 2016.

Myanmar’s first dictator General Ne Win did the first coup d’etat in March 2, 1962[2] and the second coup was in 1988 as the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC)—later called the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC)—took power after cracking the popular uprising[3]. That direct military rule ended in March 2011, transferring power to former General Thein Sein’s government.[4] This began Myanmar’s attempted period of democratization. Under the 2008 constitution, the Tatmadaw controlled one quarter of the parliament (locally called the Hluttaw) and three key ministries of Defense, Home Affairs and Border Affairs.[5] Nonetheless, Myanmar citizens experienced nominal civilian government headed by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from March 2016 to January 2021, following her National League for Democracy(NLD)’s victory in the November 2015 elections.

Five years later, Myanmar’s period of civilian rule ended as the Tatmadaw executed another coup d’etat on February 1 , 2021.[6] Since then, we have witnessed Myanmar’s political, economic and social progress being reversed. The coup makers faced strong resistance across the country. According to a high-ranking officer with the office of the Tatmadaw Commander in Chief, the military junta faced overwhelming demonstrations against the coup in the whole country except three townships.[7] The military coup and brutal crackdowns on anti-coup uprisings have produced new actors in country’s politics and armed conflict. The new actors are the National Unity Government[8], the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw[9], the Peoples’ Defense Forces[10] and many additional armed resistance groups. Currently, the Tatmadaw is facing the biggest rebellion since the 1950s. Even the Burmese generals are struggling to control armed resistance in their recruitment area of the dry zone region[11] in central Myanmar. Therefore learning about the Tatmadaw is necessary in understanding Myanmar’s politics widely and yet its relationship with regional powers also plays a role in its stability or lack thereof.

Here I would like to examine the Myanmar junta’s relations with its giant neighbour, China, from a new perspective. Usually, experts, observers and journalists working on Myanmar issues have believed the stereotype that Burmese generals are close to China and China is backing its military rulers. But that theory is nowadays difficult to defend. Information in this research is based on my interviews with insiders who are political and economic stakeholders including military officers at War Office, aides to the military and NLD leaders, diplomats, businessmen.

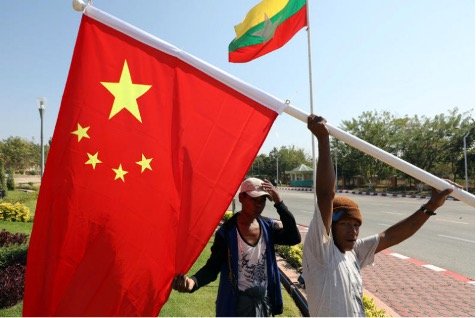

Aung San Suu Kyi welcomes Xi Jinping at the Presidential Residence in Naypyidaw on January 17,2020 (Photo: Xinhua)

Policy Review

Thanks to Beijing’s support of the military regime in Myanmar after the coup in 1988 under the policy of government-to-government ties[12], China has been a villain in most of Burmese people’s eyes. Chinese policy makers and advisors on Myanmar have acknowledged about it and it is not good as China sees its long-term strategic interest in Myanmar through its “Two Oceans Strategy,” in which China sought to exercise control over the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Both oceans are critical to sustaining Chinese growth: the Indian Ocean is the maritime highway for China’s raw materials and energy needs, whereas the Pacific Ocean is the pathway for its export-led economy [13].

Beijing conducted a Myanmar policy review in late 2009 after the Kokang war in August of that year. Amid Myanmar military’s snap offensive against the Kokang-Chinese armed group, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) which flooded 36,000 Kokang- Chinese refugees to China’s Yunnan Province[14], Beijing had reviewed its policy toward Myanmar[15]. Another significant dilemma between Beijing and Naypyidaw occurred in September 2011, when Myanmar’s Union Solidarity and Development Party government under Thein Sein decided to suspend the hydro power project in Myitsone, Kachin State in Northern Myanmar, in which China had invested billions of dollars. This move sparked Beijing’s anger.[16] For these reasons, Beijing saw its policy toward Myanmar was not working through government-to-government relations alone; it had to upgrade people-to-people relations significantly to win hearts of people of Myanmar. In order to do this, China sought to strengthen ties with popular leader Aung San Suu Kyi, whom they had seen in the past as pro-America. In early 2010, I travelled to China’s southwest province of Yunnan to report on Sino-Myanmar border affairs,[17] and I visited Yunnan University in Kunming, where the Institute of Myanmar Studies is located. Yunnan University is one of China’s handful of academic institutes where one can study Burmese language and learn about the Southeast Asian nation. Then Institute of Myanmar Studies head, Prof. Li Chenyang, was one of Beijing’s key advisors for its “Two Oceans Strategy” and CMEC or the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor. Li Chenyang, who can speak Burmese fluently, mainly asked me whether Aung San Suu Kyi was America’s lady and anti-China. My answer to Li Chenyang was that reading from her speeches and statements, Aung San Suu Kyi always expressed that Myanmar could not choose which countries it borders, and making a peaceful friendship with China is very important. During NLD’s governing period from March 2016 to January 2021, Aung San Suu Kyi’s aides echoed the statement. Her spokesman, U Zaw Htay, had made during an interview with The New York Times in 2016: “We cannot choose our neighbours.”[18]

Making New Era

After viewing its Myanmar policy, China started engaging with opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, a popular leader in Myanmar, and her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD)[19]. China had solidified ties with Aung San Suu Kyi and her party as early as 2013. Dozens of NLD officials had visited to China throughout years.[20] China named U Aung Shin, writer turned one of NLD’s founding members as NLD’s de facto special envoy to China. In January 2021, just days before his arrest following the coup on February 1, 2021, U Aung Shin told the author that he had made dozens of visits to China in 2013-20.

As for Aung San Suu Kyi, she made her first visit to China as Myanmar’s opposition leader in June 2015. Xi Jinping hosted her at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China’s first remarkable treat to the Myanmar opposition leader as a stateman. Due to her health issue, she was about 20 minutes late to arrive to the meeting. But the Chinese leaders reportedly made joke instead of angry at her saying she was the first person ever to have kept him waiting so long[21] Before and during Myanmar’s elections in 2015, Chinese officials were closely monitoring the NLD’s activities too. Officials of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) even accompanied Aung San Suu Kyi on her campaign trip to the Irrawaddy delta. After she became State Counsellor or de facto leader of Myanmar, she chose to visit Beijing in August 2016, before visiting to Washington D.C. She made several visits to China after that, before Xi Jinping launched China’s leader’s first visit to Myanmar in nearly two decades in early 2020, promising for billion dollars investment in the country.

In fact, China was maximizing its relations with Aung San Suu Kyi during the five-year rule of the NLD. China also improved people-to-people relations with Myanmar under Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership. For instance, China hosted huge public events for Chinese New Year Festival in China Town in downtown Yangon, Myanmar’s largest city[22], compared to smaller indoor events after the coup.[23]

Learning the Past

What we know about China-Myanmar relations is that China is the closest ally and main arms supplier of the Myanmar military. What isn’t commonly known is that China’s ties with the Myanmar military are not always warm. Before Xi Jinping’s trip in January 2020, the last visit of China’s leader, Jiang Zemin, was in December 2001.[24] Jiang Zemin’s concluded his trip with outrage when Myanmar junta supremo Senior General Than Shwe’s rejected[25] China’s proposal for a highway from the China border to Bhamo, Kachin State and an Irrawaddy water way from Bhamo to the Irrawaddy delta, the gateway to Indian Ocean. The proposal was part of China’s “Two Oceans Strategy”. According to author’s interview with a former senior staff officer who used to work under Than Shwe, the junta supremo frequently expressed that the primary external threat was not really Western invasion, but Myanmar’s giant neighbours. “The senior general told us that Myanmar lives between two giant countries, China and India. That’s why, he said, we have to be careful,” the former major general said.

It is important to remember that current junta head General Min Aung Hlaing’s leadership is the third generation of the Myanmar military dictatorship. The first and second generation of Myanmar military leadership had risen in the ranks throughout battlefield fighting against rebels backed by China’s People’s Liberation Army. Although China became the Myanmar military’s friend in need after the 1988 coup, Burmese generals still see China as a onetime enemy, and China’s trust in Burmese generals is also doubtful. For example, Burmese former and current military officers complained that Chinese-made surveillance drones are they had purchased are not working well along the Sino-Burmese border, and they suspected China of selling low quality equipment to the Myanmar military.

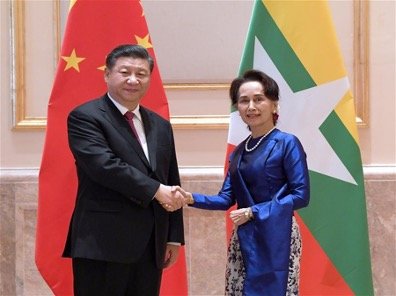

Myanmar junta chief Min Aung Hlaing (left) shakes hands with China’s Premier Li Qiang in Kunming on November 6, 2024. (Photo: AFP)

Cold Tie after the Coup

Beijing’s first statement officially responding to the 2021 coup was that it “hope[s] that all sides in Myanmar can appropriately handle their differences under the Constitution and legal framework and safeguard political and social stability.”[26] What the public didn’t see was China’s behind-the-scenes pressure on the SAC. According to Myanmar military sources, Beijing sent a senior Chinese diplomat to Naypyidaw shortly after the coup to play mediator amidst political turmoil after the coup; this diplomat requested to meet with detained Aung San Suu Kyi. Beijing’s message was that “all parties and factions in Myanmar in bridging differences and resuming the political transition process through political dialogue within the constitutional and legal frameworks.”[27] From February 2021 to August 2024, Chinese senior diplomats such as Wang Yi, Qin Gang, Deng Xijun and Sun Guoxiang visited Myanmar at least 10 times in effort to resolve the crisis in the neighbour. But China’s immediate efforts did not go well. Min Aung Hlaing repeatedly rejected China’s request to access the ousted leader which the rising global power of China saw as an “insult.” (According interviews with SAC officials, they anonymously said Min Aung Hlaing himself rejected China and U.N.’s request to meet the detained ousted leader although other generals wanted to allow.)

In response, China suspended all money going to Myanmar except humanitarian aid. Shortly after the coup, an oligarch who runs a bank told the author that he thought SAC could handle the economy well, adding that China would inject at least $ 1.5 billion. But it seemed not to happen. According to Burmese businessmen, China paused all key investments in Myanmar after the coup even though it didn’t impose economic sanctions on the junta. Nowadays Myanmar’s inflation has increased threefold; a dollar is now 4,550 Myanmar kyat, jumping from 1,300 Myanmar kyat before the coup. The SAC is still struggling to handle its biggest challenge to the country’s economy.

Meanwhile, distrusting on the giant neighbour in eastern border, the Burmese junta pursued closer ties with Russia,[28]attempting to replace China’s alliance with another global power. But SAC’s move has backfired, damaging Sino-Myanmar ties more. China’s policy is clear: it is friends with Russia, and Xi Jinping can trade pancakes and vodka with Russian President Vladimir Putin.[29] But China doesn’t want another global super power next door. One example of this regional concern is when China’s PLA troops invaded northern Vietnam in 1979, just a few months after Vietnam signed military and commercial treaty the then Soviet Union. Yet current leaders are not necessarily aware of this history. Over the past four years, the SAC has signed multiple treaties with Russia, including military agreement that allows the Russian Navy to use Myanmar ports such as the strategic Great Coco Island in the Andaman Sea. During an informal interview with SAC’s advisor and staff officers at the commander-in-chief office, I asked whether the SAC had historical knowledge about China’s Vietnam invasion. Their answer was “No Idea”. Until his first trip to China’s Yunnan Province in November, Min Aung Hlaing’s most recently visited country was Russia. Until his first visit to China in November, Min Aung Hlaing’s most visit country in the planet is Russia after the coup. He is also enjoying trading honourable titles between Myanmar and Russian leaders[30].

Although China doesn’t have “regime change policy” in Myanmar, it may want to test strength of the Tatmadaw, once it was described as the second strongest in Southeast Asia after Vietnam’s and a big lesson to the SAC as the tie has been backward since the coup. Then, on October 27, 2023, the pro-China ethnic armed group alliance, the 3 Brotherhood Alliance of Kokang’s MNDAA, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and the Arakan Army (AA) launched Operation 1027, a coordinated and successful offensive against the Myanmar Army in northern Shan State[31]. Intentionally or not, that is exactly the same day that a naval group of the Russian Pacific Fleet was sailing from Indonesia[32] to Myanmar for the first Russian-Myanmar joint naval drill[33], which was completed on November 7, 2023. Even pro-military social media posts at the time criticized Min Aung Hlaing for being too busy hosting Russian navy chief Admiral Nikolai Yevmenov and his navy group at the drill, rather than responding to Operation 1027.[34]

If we compare the SPDC and SAC’s foreign policy, we see Than Shwe practiced an on-and-off foreign policy with confidence. Even Than Shwe allowed the then U.N. special envoy to Myanmar, Malaysian diplomat Razali Ismail to meet Aung San Suu Kyi shortly after the deadly attack on her convoy in Depayin, central Myanmar by pro-miliary thugs in May 2003.[35] But Min Aung Hlaing has closed all doors in diplomacy,[36] even to China, leaving Aung San Suu Kyi without foreign visitors in four years.[37] Another key point to note about the failure of Min Aung Hlaing’s foreign policy in relation to China before Operation 1027 was SAC’s lack of cooperation with China over online scammer gangs operating in Myanmar’s soil, which China considered a matter of national security. In response, China seems to be considering direct or indirect intervention[38] in Myanmar. In the wake of the online scammers issue, the 3 Brotherhood Alliance clearly stated that one of main goals in launching Operation 1027 was to crack down the online scammers on the Sino-Burmese border.[39]

Senior General Min Aung Aung alongside Russian Navy Chief Admiral Nikolai A Evmenov on a Russian navy vessel on November 6,2023. (Photo: MNA)

China’s Calls

After nine months of Operation 1027, in July 2024, the pro-China resistance forces had overrun the Myanmar Army’s posts in strategic towns and cities in northeastern and western Myanmar. The Myanmar Army lost its North-East Regional Military Command in Lashio, the capital of northern Shan State, 190 km from the Sino-Burmese border on major trade route on July 25.[40] It was the biggest defeat for the Myanmar army since 1950s. After losing Lashio headquarters, the SAC leadership reportedly decided to review their China policy and China’s proposal for Myanmar’s political deadlock.[41] Just before fall of Lashio, former Myanmar President Thein Sein travelled to Beijing for the 70th anniversary of China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence[42] in late June, even allowing his photo shaking hands with Xi Jinping to appear in a pro-junta media outlet.[43] After that trip, the former president reportedly brought China’s messages to Naypyidaw: release Aung San Suu Kyi and NLD leaders, begin an all-inclusive political dialogue, hold elections, and end of the SAC rule.

Then, China’s special envoy to Myanmar, Deng Xijun came to Naypyidaw meeting the SAC leadership,[44]making the final negotiation before Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi’s visit there, meeting with Min Aung Hlaing in the same month[45]. Military sources suggested Min Aung Hlaing allowed Wang Yi’s meeting with Aung San Suu Kyi on the trip although both sides didn’t say anything about it officially. Min Aung Hlaing made his first trip to China after the coup in November, not to Beijing but a regional meeting in Kunming.[46] After returning from China before the new year, Min Aung Hlaing appointed Quartermaster-General Lieutenant General Kyaw Swar Lin as joint-Chief of Staff (Army, Navy, Air Force), the third highest ranking post in the Myanmar military, setting his successor if he steps down from the military.[47] The state media more frequently reported about the junta’s plan for elections too.[48] With China’s pressure, the Kokang army of the MNDAA announced last month that they signed a ceasefire with the Myanmar army after a series of talks in China,[49] and planned to withdraw their troops from Lashio later this year.[50]

The Brotherhood Alliance at the main gate of Myanmar Army’s Northeastern Regional Military Command in Lashio, Shan State in August 3, 2024. (Photo: MNDAA)

Conclusion

Meanwhile, the United States under the Trump presidency is turning away global issues perhaps including Asia and Myanmar. Even his Secretary of Defence, Pete Hegseth had difficulty naming the member of ASEAN[51]. The United States doesn’t have much interest in the Southeast Asian nation, compared to China’s consistent attention.[52]Thus China will be expanding its influence over all stakeholders of Myanmar in coming years. During his trip to Myanmar in August, Wang Yi met with Min Aung Hlaing’s predecessor and mentor, Than Shwe, telling the 91-year-old general that China supports Myanmar to “reach domestic political reconciliation within the constitutional framework, hold national elections smoothly and restart the process of democratic transformation.”[53] His words reflect what China wants to see most in Myanmar in coming years: to get away from the current political crisis which is more secured for its geopolitics and economic interests in the country.

References:

- Andrews, M. (2020). Myanmar’s Political Evolution and China’s Role. Cambridge: Global Affairs Press.

- Brown, T. (2018). Geopolitics in Southeast Asia: Myanmar’s Strategic Challenges. Singapore: Southeast Asian Studies Institute.

- Htay, U. Z. (2016). Interview with The New York Times.

- Jones, R. (2019). Economic Ties Between China and Myanmar: A Historical Perspective. London: Oxford Economic Studies.

- Li, C. (2017). China’s Two Oceans Strategy: Myanmar’s Role. Beijing: Academic Press.

- Lin, J. (2023). Regional Conflicts and China’s Security Interests in Myanmar. Shanghai: East Asia Institute.

- Smith, M. (2010). Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London: Zed Books.

- Sun, H. (2021). China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Myanmar’s Infrastructure Development. Beijing: Silk Road Publications.

- Wang, Y. (2022). China’s Diplomatic Challenges in Southeast Asia. Beijing: Foreign Affairs Press.

- Zhang, W. (2021). China-Myanmar Relations: Past, Present, and Future. Hong Kong: China Review Press.

- Zhou, K. (2023). Myanmar’s Military Strategy and International Relations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Note:

[1] https://www.neglobal.eu/understanding-the-complicated-politics-and-geopolitics-of-the-coup-in-myanmar/

[2] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v23/d49

[3] https://www.npr.org/2013/08/08/210233784/timeline-myanmars-8-8-88-uprising

[4] https://www2.irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=21040

[5] The Myanmar Constitution 2008, Chapter IV and V.

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/31/world/asia/myanmar-coup-aung-san-suu-kyi.html

[7] Interviewing with an officer.

[8] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/opponents-myanmar-coup-announce-unity-government-2021-04-16/

[9] https://www.crphmyanmar.org/who-we-are/

[10] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/5/6/myanmars-anti-coup-bloc-to-form-a-defence-force

[11] https://fulcrum.sg/myanmars-dry-zone-the-history-of-a-tinderbox/

[12]https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://digital.library.tu.ac.th/tu_dc/digital/api/DownloadDigitalFile/dowload/121103&ved=2ahUKEwil5pjwy6aLAxXwRWwGHX2SLdgQFnoECBQQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0EuHJiXqsym0A0kcIklfSq

[13]https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/guest-column/chinese-president-xi-jinpings-myanmar-trip-aimed-pushing-beijings-two-ocean-strategy.html

[14] https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/31/world/asia/31iht-myanmar.html

[15] Interview with Chinese scholars in 2010.

[16] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/oct/04/china-angry-burma-suspend-dam

[17] https://www2.irrawaddy.com/print_article.php?art_id=18223

[18] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/14/world/asia/myanmar-aung-san-suu-kyi-sanctions.html

[19] https://archive.nytimes.com/sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/26/beijing-seems-to-be-warming-toward-aung-san-suu-kyi/

[20] https://archive.nytimes.com/sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/26/beijing-seems-to-be-warming-toward-aung-san-suu-kyi/

[21] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/18/world/asia/visiting-beijing-myanmars-aung-san-suu-kyi-seeks-to-mend-relations.html

[22] https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1WiEh1kNzJ/

[23] http://mm.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/sgxw/202501/t20250127_11546915.htm

[24] http://en.people.cn/200112/13/eng20011213_86540.shtml

[25] Author’s interview with a former major general at War Office of Myanmar military

[26] https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-notes-myanmar-coup-hopes-stability-2021-02-01/

[27] https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/wjbzhd/202305/t20230502_11069444.html

[28] https://fulcrum.sg/myanmars-pivot-to-russia-friend-in-need-or-faulty-strategy/

[29] https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2018/09/12/putin-xi-make-pancakes-drink-vodka-together-vladivostok-a62853

[30] https://www.myanmaritv.com/news/receiving-title-sac-chairman-received-title-bestowed-russian-president

[31] https://myanmar.iiss.org/updates/2023-11

[32] https://tass.com/defense/1697683

[33] https://tass.com/defense/1700919

[34] https://www.myawady.net.mm/sites/default/files/volume%20IV%2C%20Eng%20Issue%2022%20%288-11-2023%29.pdf

[35] https://www2.irrawaddy.com/print_article.php?art_id=20064

[36] https://www.voanews.com/a/thailand-calls-regional-talks-on-war-torn-myanmar-frank-but-short-on-agreement-/7909022.html

[37] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/no-contact-how-myanmars-junta-isolated-daw-aung-san-suu-kyi-from-the-world.html

[38] https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/china-edges-closer-to-intervention-in-myanmar/

[39] https://x.com/operation1027/status/1717745581425361087

[40] https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/kokang-army-says-it-has-captured-myanmar-juntas-northeastern-regional-military-command-hq/

[41] Author’s interview with military sources

[42] https://www.channelnewsasia.com/asia/myanmar-china-junta-thein-sein-soe-win-cna-explains-4467241

[43] https://cnimyanmar.com/index.php/english-edition/23036-photos-of-chinese-president-xi-jinping-and-myanmar-ex-president-u-thein-sein-shaking-hands-emerge

[44] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/myanmars-crisis-the-world/chinese-special-envoy-in-myanmar-for-junta-talks.html

[45] https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjbzhd/202408/t20240815_11474224.html

[46] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5yr8exg1gko

[47] https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-boss-promotes-loyalist-in-regime-reshuffle.html

[48] https://www.gnlm.com.mm/election-to-form-pyithu-hluttaw-amyotha-hluttaw-regional-and-state-hluttaws/

[49] https://english.news.cn/20250120/ac5e8992a61d4e6b9892e69187018829/c.html

[50] https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/kokang-army-to-withdraw-from-lashio-under-chinese-brokered-ceasefire-with-myanmar-junta/

[51] https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/question-asean-stumped-hegseth-senate-hearing-important-rcna187909

[52] https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/opinion-6-reasons-us-is-not-really-supporting-myanmar-s-democratic-resistance/2699374

[53] https://www.mfa.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjbzhd/202408/t20240815_11474236.html