Establishing an Effective Privacy Policy in Myanmar: Analysis and Review of the Current Privacy Context and Approach to Amend Failed Privacy Policy

Author: Zun Pwint Phyu (AKA) Zee Pe

Introduction

Although Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution stated to protect the privacy of citizens and the legal system includes privacy and personal safety, Myanmar has no specific policy to protect the privacy of citizens. The existing privacy regulation in Myanmar’s legal system failed to protect the privacy of citizens, it only protects powerful individuals and institutions like the government, politicians, and celebrities. That’s why, citizens are losing their rights to practice freedom of expression and criticism and they face legal threats and severe criminal punishments. In addition to that, telecoms and corporations have the freedom to handle and process the personal data of citizens and have agreements with the government to share the flow of data.

Background and Definition of Privacy

In this age of sky-rocketing technology, privacy matters more than before in history. The more our information is exposed, the more danger we have. Criminals are not the only group to breach our privacy, but also the government violates our privacy. A well-established privacy policy limits the power of the government that will not be able to interrupt the personal privacy of its citizens. It is too dangerous for the government and citizens if any national information gets stolen. The danger is beyond anticipation to store those data and information in the wrong hands. The privacy of many individuals is now under threat globally, and many countries have taken actions to protect the privacy of people, which means national privacy.

What is Privacy?

Privacy is defined as the right to be alone or securely stay away from interference, or intrusion. As discussed above, it comprises two types; physical personal privacy and digital data privacy. The first one means securing the personal information of individuals such as addresses, names, and ID numbers that are identified or identifiable of those individuals. The latter is to keep the digital data of individuals safe, for example, credit card numbers, bank information, user behaviors, political desires, social media accounts, and phone numbers.

Why does the privacy policy matter?

Privacy matters because the personal information of individuals can be misused, by any party, like criminals, other misguided individuals, or even the government. Conflicts, and chaos can be created by misusing those data. Many crimes can happen, and the consequences will be more harmful than anticipated if the privacy of individuals is insecure. Privacyis also considered trust. When private information about an individual is in the wrong hands, their life can be controlled. Freedom of thought and speech can be limited if the state violates the privacy of fellow citizens. In addition to that, it also restricts social and political actions.

Privacy Policy Around the World

Several countries in the world are enacting their first privacy and data protection policies, or they are amending the existing ones. China, one of the world’s largest nations, passed the first national privacy law in 2021. Japan and Korea amended their privacy protection policies and Australia reviewed their three decades old Privacy Act in the last two years. Countries in the Asia Pacific region took models of privacy policy frameworks from developed countries, such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The situation of the privacy policy and regulation in the ASEAN region is not even. Not all countries have specific regulations to protect the personal data and privacy of the citizens. Only a few countries including Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand in 2019 have privacy regulations. But countries like Myanmar, Brunei, and Cambodia have no specific regulations on personal data protection policy.

Problem Statement: Lack of Privacy Policy in Myanmar

Myanmar has the reputation of setting up surveillance systems to monitor the communication of oppositions. Although the constitution stated to protect the privacy of the citizens, the legal system is failed to protect it, instead adding severe punishment against the citizens that prevent them from practicing their freedom of expression. Although Myanmar began political reforms in 2010, the state set up intensified frameworks to interfere and monitor the communications between the citizens after the political turmoil in 2013.

Previous administrations enacted and drafted some legal regulations that are meant to protect the privacy of the citizens. But privacy rights of many Myanmar people were violated. The NLD administration of Myanmar enacted the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens in 2017, which disallowed military intelligence and the Special Branch police to follow after citizens, and many other privacy breaches from law enforcement, and intelligence. But many journalists and activists were in jail for criticizing the government, state leaders, and celebrities under the same law. Moreover, the privacy of millions of individuals is under threat, significantly getting higher, especially after the coup in February 2021 due to the amendment of the stricter privacy regulations done by the military regime.

Corporates including telecom service providers do not required to follow privacy regulations since the governments of Myanmar didn’t impose any regulations like that, not even included in the most recent consumer protection act. In addition to that, they required to give the data of citizens to the government when it is being asked.

Policy Analysis: Review of the Current Privacy Regulation

Electronic Transaction Law enacted in 2004, later amended by the military regime in 2021 was the first law to be discussed in the review process of the current privacy regulation in Myanmar. This law do not protect the data privacy of the citizens as per the objectives. Section 357 of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution states to protect the privacy of citizens. The NLD administration enacted “The Law Protecting the Privacy & Security of Citizens” in March 2017. The purpose of this law is to comply with the constitution, which is to protect the privacy of the citizens, thus it has good intentions. But the civil society in Myanmar criticized and opposed the law because the provisions were controversial and vague, especially in article 8 (f) and 10, that was used to take legal actions against some individuals, although it was intended to be for protection. Article 8 (f) limited the interference of police or other intelligence bodies. Before this law, Myanmar had a “Nightly Registration Rule” which means everyone sleeping at a household was required to register at the administration office. But after this law was passed, the NLD administration revoked the nightly registration rule. Article 8 restricted the interference of the Special Intelligence and police officers who are known for following after journalists, activists, or opposition groups.

The most controversial clause, the Article 8(f) of the law, which is vague and has similar provisions in Section 500 of the Penal code, stated that “In the absence of an order, permission or warrant issued in according with existing law, or permission from the Union President or a Union-Level Government body: No one shall unlawfully interfere with a citizen’s personal or family matters or act in any way to slander or harm their reputation.”

More than 20 people were sued by the same article during the time of the NLD administration between 2016-2020. Thefreedom of expression and ideas of citizens were limited because of this article of the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens. Criticizing the administration, any high-level politicians, or anyone else in the country is considered a practice of freedom of expression and fundamental human rights. Social justice analysis is a proper tool for the establishment of the privacy policy in Myanmar.

The other section of Article (10) said “Whosoever is found guilty of committing an offense under Section 7 or 8, shall, in addition to a sentence for a period of at least six months, and up to three years, also be required to pay a fine of between three hundred thousand (300,000) to fifteen hundred thousand (1,500,000) kyats.

Cyber Security Law drafted in 2019 was postponed to being enacted due to several criticisms. The Myanmar military regime sent to different ministries to ask for recommendations in February 2021, a week after the illegitimate coup. This drafted version done by the military has no clause to protect the data privacy of the citizens, and it has several clauses that barred the practice of the freedom of expression.

Policy Recommendation: All-Inclusive Privacy Policy

The compliance tool is to establish an effective privacy policy that protects the personal data and privacy data of citizens, without harming the practices of freedom of expression. The policy framework should be based on the idea that citizens have full rights to protect their private personal data, and no one is able to manage or handle those data without consent. Myanmar’s privacy policy shall shelter everyone in the country equally, not just one person or institution without violating the rights of citizens.

Recommendations to enact a new policy or amend an existing policy at the current Myanmar can be more complicated in this revolutionary period while the elected members of parliament were forced to flee their constituencies. Thus, this recommendation is to be taken initiative by the civil society and the international advocacy groups; and prepare a draft that is going to be ready to enact aftermath of the revolution against the military regime. (Access Now, 2022)

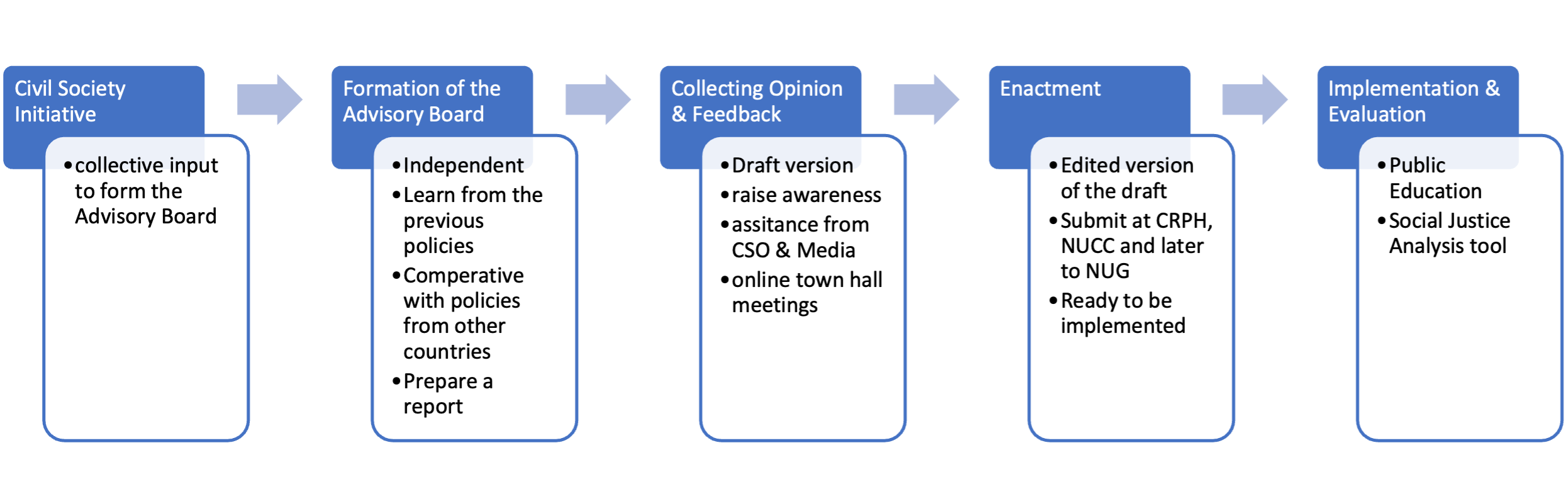

7.1 Civil Society to Take Initiative

The civil society of Myanmar should take initiative in the establishment of the effective privacy policy because none of the Myanmar administration was successful to protect the privacy of the citizens, and the current military regime that rules the country has no interest in protecting the privacy of citizens. Myanmar Civil Society shall unite and form an independent all-inclusive advisory board to work on the new privacy policy of Myanmar, that is going to be submitted at the National Unity Government and National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC).

7.2 Formation of Advisory Board

The advisory board to enact the privacy policy of Myanmar should be formed with the equal participation of different stakeholders.

- Representatives of civil society

- Lawyers and legal experts

- Representatives of the ex-pat community

- Representatives of journalists and artists’ community

The role of the advisory board is to be independent, not leaning towards any political or business groups. The board is to collect information about trials and lawsuits that happened during the time of previous administrations. Then, prepare a report based on that information to compare with the privacy policies around the world (such as the EU Privacy Policy) before submitting the draft version of the policy.

7.3 Opening the Drafted Policy for Opinion & Feedback

Once the draft version of the policy is published, the advisory board is to open it to the public for opinion and feedback. It will allow the public to raise awareness about privacy issues that were never raised before. The advisory board seeks assistance from civil society and the media to make online town hall meetings where feedback and opinions are going to be collected.

7.4 Enactment of the Privacy Policy for New Myanmar

The draft version will be edited based on the collective feedback and the opinion, and later to finalize the policy. Then, it is to submit at the NUCC for the review process and later submitted to the CRPH – Committee Representing the Pyihtaungsu Hluttaw, the formation of the elected members of the parliament. Then, the policy will be ready to be implemented by the National Unity Government once the revolution is successful.

7.5 Implementation and Evaluation

The implementation process after the revolution begins with public education on what privacy is and why it matters. The advisory board will still be active even after the policy is implemented to monitor and evaluate if the regulations and policies are effective and fair for everyone. The board is to use “the Social Justice tool” to measure whether this new privacy policy can protect personal and private data.

Figure: Deliberative Policy Approach to the Establishment of an Effective Privacy Policy

References

- Korunovska, Jana & Spiekermann, Sarah & Kamleitner, Bernadette. (2020). THE CHALLENGES AND IMPACT OF PRIVACY POLICY COMPREHENSION.

- Rosenquist, M., CISO, & Eclipz.io. (2020, July 28). What is privacy and why does it matter? Help Net Security. https://www.helpnetsecurity.com/2020/07/28/what-is-privacy-and-why-does-it-matter/

- Myanmar – Data Protection Overview. (2022, September 28). DataGuidance.

Myanmar – Data Protection Overview | Guidance Note | DataGuidance - Chilman, C. (2022). Understanding Personal Privacy Issues in Information Technology. Study.com.https://study.com/learn/lesson/personal-privacy-issues-information-technology.html

- Tobin, D. (2021, May 7). What is Data Privacy—and Why Is It Important? Integrate.io. What is Data Privacy—and Why Is It Important? | Integrate.io

- Unofficial Translations MCRB Consolidating the Amendments in Law 04/2021. (2021, April).www.myanmar-responsiblebusiness.org

- Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens (the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Law 5/2017) ⢠Page 1 ⢠CYRILLA: Global Digital Rights Law. (n.d.). Retrieved November 1, 2022, fromhttps://cyrilla.org/fr/entity/ib4qvhe7vbl?file=1588587259059qit5ooma2pb.pdf

- Athan Myanmar. (2019, April). Analysis of Law on Protecting the Privacy & Security of Citizens.www.athanmyanmar.org

- What is personal data? (2018, August 1). European Commission – European Commission.https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/data-protection/reform/what-personal-data_en

- Confessore, N. (2018, April 4). Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: The Scandal and the Fallout So Far. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/04/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-scandal-fallout.html

- How You’re Affected by Data Breaches. (2020, June 5). CIS.https://www.cisecurity.org/insights/blog/how-youre-affected-by-data-breaches

- Rosenberg, M., Confessore, N., & Cadwalladr, C. (2018, March 17). How Trump Consultants Exploited the Facebook Data of Millions. www.nytimes.com.https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/17/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-trump-campaign.html

- Rosenberg, M., & Frenkel, S. (2018, March 18). Facebook’s Role in Data Misuse Sets Off Storms on Two Continents. www.nytimes.com. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/18/us/cambridge-analytica-facebook-privacy-data.html

- EUR-Lex – 32016R0679 – EN – EUR-Lex. (2016). Europa.eu. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1552662547490&uri=CELEX%3A32016R0679

- Thales Group. (2019, September 30). Data protection regulation around the world. Thalesgroup.com.https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/markets/digital-identity-and-security/government/magazine/beyond-gdpr-data-protection-around-world

- Privacy HQ. (n.d.). Data Privacy Rankings – Top 5 and Bottom 5 Countries – Privacy HQ. Privacyhq.com.https://privacyhq.com/news/world-data-privacy-rankings-countries/

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2021). Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide | UNCTAD. Unctad.org. https://unctad.org/page/data-protection-and-privacy-legislation-worldwide

- Bartels, K. P. R., Wagenaar, H., & Li, Y. (2020). Introduction: towards deliberative policy analysis 2.0. Policy Studies, 41(4), 295–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2020.1772219

- Perria, S. (2018, January 1). Rough justice in Myanmar as legal system creaks. Financial Times.https://www.ft.com/content/2aa3b8a4-5d89-11e7-b553-e2df1b0c3220

- ALI MOHIB, S., DAVIDSEN, S., & BOOTHE, R. (2016, October). Myanmar – Participating in change: Promoting public sector accountability to all. Blogs.worldbank.org.https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/myanmar-participating-change-promoting-public-sector-accountability-all

- Free Expression Myanmar. (2017). Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens – Free Expression Myanmar. Freeexpressionmyanmar.org. https://freeexpressionmyanmar.org/laws/law-protecting-the-privacy-and-security-of-citizens/

- Myanmar Center for Responsible Business. (2019). POLICY BRIEF A DATA PROTECTION LAW THAT PROTECTS PRIVACY: ISSUES FOR MYANMAR. https://www.myanmar-responsiblebusiness.org/pdf/2019-Policy-Brief-Data-Protection_en.pdf

- Cooper, A. (2022, January 27). Privacy Policy: What to Expect Around the World in 2022. BSA TechPost. https://techpost.bsa.org/2022/01/27/privacy-policy-what-to-expect-around-the-world-in-2022/

- Tse Gan, T., Cyber Risk Leader, & Deloitte Southeast Asia. (2018). Personal Data Protection in ASEAN. https://www.zicolaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/ASEAN-INSIDERS_PDPA-in-ASEAN-3.pdf

- Radio Free Asia. (2022, April). More than 130 journalists arrested in Myanmar, media group says. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/journalists-04042022154255.html

- Tun, A. (2022, June 30). Restoring Privacy Rights, a Must for Ending Myanmar’s Violence. FULCRUM. https://fulcrum.sg/restoring-privacy-rights-a-must-for-ending-myanmars-violence/

- Access Now. (2022, January 27). Analysis: the Myanmar junta’s Cybersecurity Law would be a disaster for human rights. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/analysis-myanmar-cybersecurity-law/

- Oxley, Douglas. Fairness, Justice and an Individual Basis for Public Policy Fairness, Justice and an Individual Basis for Public Policy. 2010.