Securing Credential Recognition for Myanmar’s Online Education in Post-Coup

Author: Wyne Ei Htwe

Advisor: Ora-orn Poocharoen

Executive Summary

The study analyzes the impact of the 2021 military coup on Myanmar’s education system, focusing on the role of online educational platforms during the political unrest. It highlights challenges related to the recognition and accreditation of qualifications offered by these platforms and provides strategic recommendations for improving online education’s legitimacy, quality, and global integration in Myanmar. The report concludes by urging the National Unity Government to implement these recommendations to secure educational opportunities and contribute to a resilient, inclusive, and quality-focused education system for Myanmar’s future.

Background

The education system in Myanmar has historically been a center for activism and change. Students have a history of leading protests against oppressive governments. The recent military coup in 2021 has led to significant disruptions in the education landscape. Thousands of teachers and educators have united with young activists in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) to protest the military’s control over education.

Despite the junta’s announcement to reopen universities in May 2021, most students have boycotted the universities controlled by the junta, resulting in a significant decrease in enrollment.

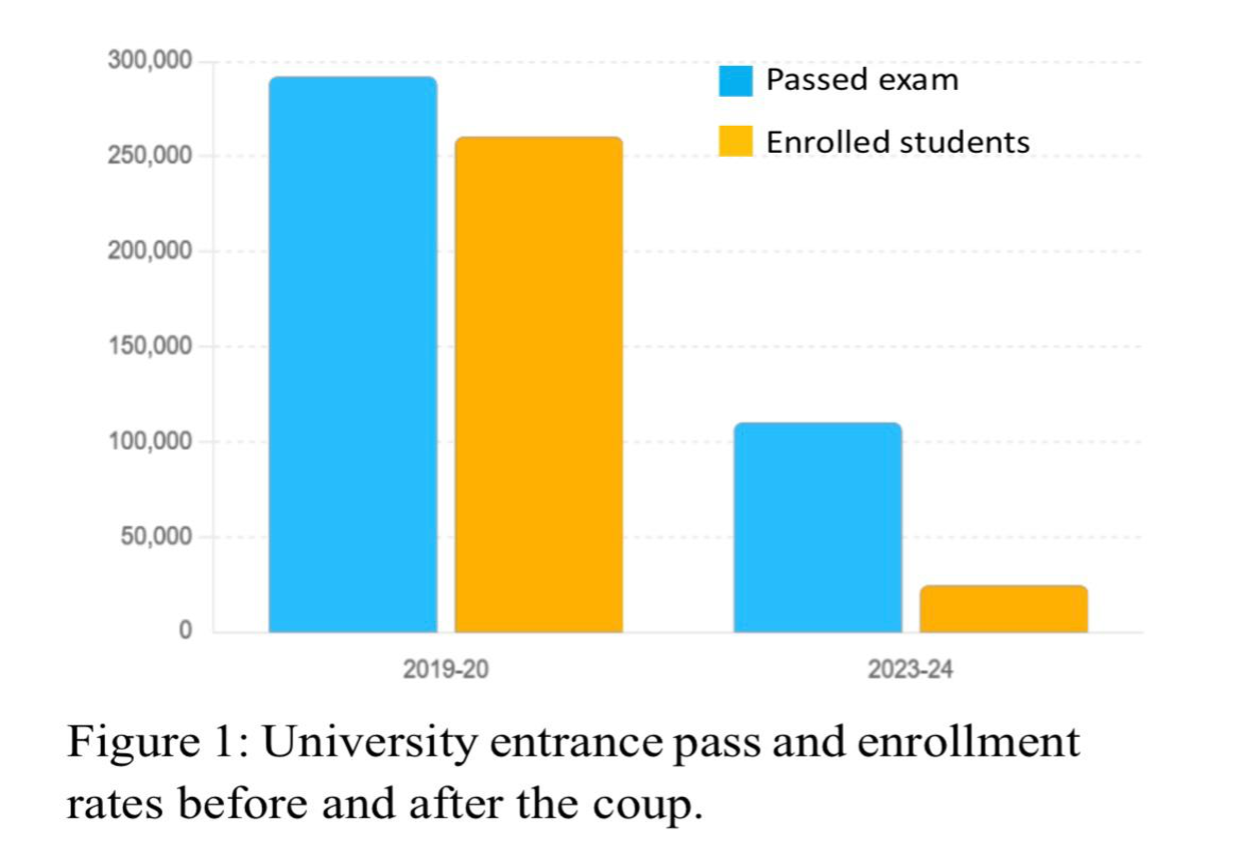

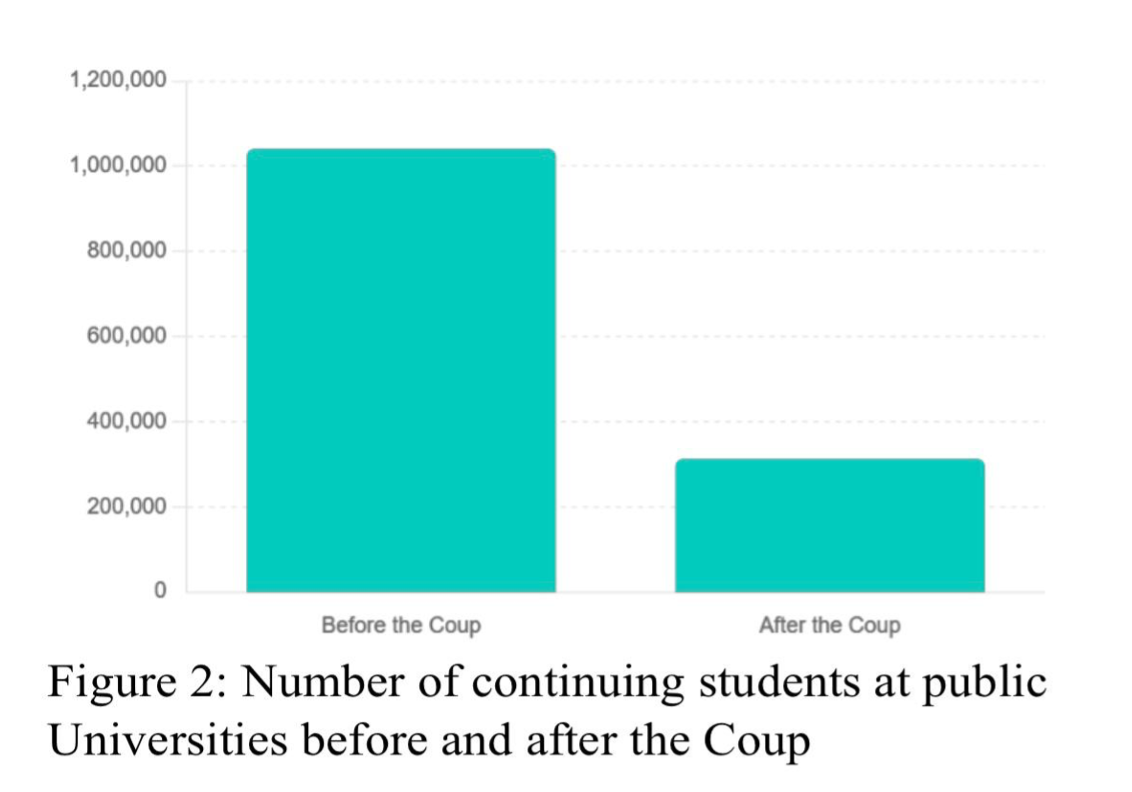

For the 2023-24 academic year, only 24,243 students were enrolled, compared to 109,851 who passed the university entrance exam (Radio Free Asia, 2024). This is a substantial drop from the 260,173 enrolled for the 2019-20 academic year, despite 291,798 passing the exam (Radio Free Asia, 2024). Additionally, the number of continuing students at public universities decreased from 1,040,393 before the coup to 312,118 after the coup (Spring University Myanmar, 2023). This sustained educational boycott demonstrates a nationwide solid commitment to the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), with young people determined to suspend their formal education until the State Administration Council (SAC) is overthrown (Francesca Chiu, 2024).

In the meantime, innovative educational solutions such as Ethnic Education Departments, Online Education Platforms, and Interim University Councils have emerged due to this resistance. These initiatives are crucial for ensuring access to education despite the military’s actions and ongoing violence. Online education platforms have become essential for meeting the educational needs of students in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) who are looking to continue their studies outside the control of the military. The Ministry of Education, National Unity Government, is also actively supporting initiatives like Myanmar Nway-Oo University, which is designed for students boycotting junta-run universities.

Meanwhile, a large majority of students—97.9%—strongly desire for their courses to be recognized by international educational institutions, underscoring their need for credentials that further their academic and professional goals (Spring University Myanmar, 2023). Without recognition, students might encounter difficulties in transferring credits, pursuing higher degrees, and securing job opportunities, affecting their confidence, drive, and economic potential.

Methodological Note

This policy brief is based on a thorough qualitative data analysis of interviews with administrators of online educational platforms in Myanmar. These insights are instrumental in shaping the targeted recommendations to improve the accreditation and quality assurance of these platforms.

Limitations of Analysis

This brief acknowledges that while online education presents a viable solution for continuing education amidst Myanmar’s current political turmoil, it is not universally accessible.

Internet restrictions and military shutdowns significantly limit online education’s reach, particularly affecting those in remote and conflict-affected areas. These limitations highlight the necessity for the National Unity Government to consider supplementary strategies that address educational access across all regions, ensuring no community is left behind in educational initiatives.

Policy Analysis

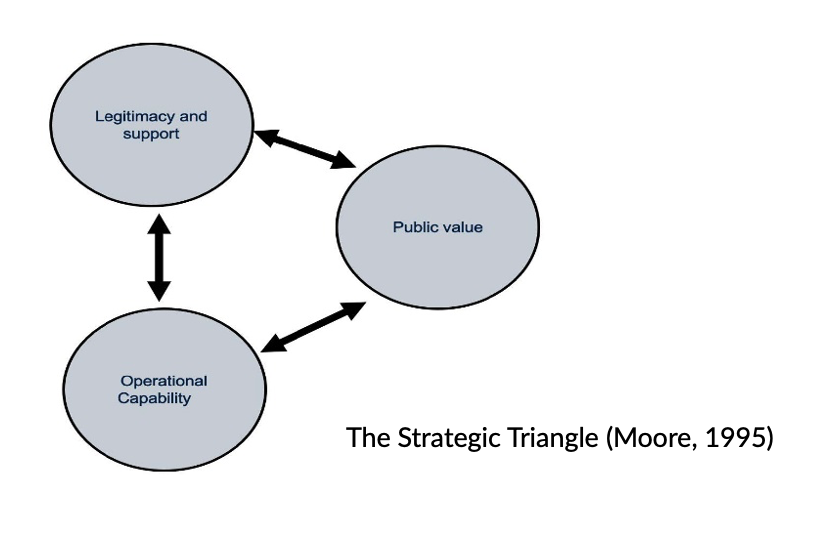

The growth and function of online educational platforms in Myanmar are examined using Mark Moore’s Strategic Triangle model. This model evaluates public services with three interlinked elements: Public Value, Legitimacy and Support, and Operational Capacity. These components are crucial for assessing educational platforms’ effectiveness, sustainability, and societal impact under challenging conditions.

Public Value (Vision of Online Educational Platforms)

Public Value, as defined by Moore, refers to the contribution an organization makes to society. In the realm of online educational platforms, this extends to increasing educational accessibility and promoting democratic empowerment. In Myanmar, online educational platforms are driven by a vision of social justice, educational accessibility, and democratic empowerment. These platforms are not simply substitutes for traditional education; rather, they are transformative forces that embed principles of social justice and empowerment into their fundamental missions. Their goal is to educate Myanmar’s youth during challenging times, while also generating support for vulnerable communities and advocating for democratic values. This dedication demonstrates how education can drive societal change and create stability during difficult times.

Legitimacy and Support (Accreditation Challenges and Partnerships)

According to Moore, legitimacy and support are crucial for an organization. For educational platforms, gaining accreditation, recognition of educational offerings, and partnerships with educational institutions, NGOs, and government entities are key factors in enhancing operational legitimacy and ensuring educational services are valued and recognized.

All administrators interviewed mentioned that workplaces and other institutions in Myanmar often hesitate to recognise certificates issued by their platforms as their platforms are openly opposed to the junta so those workplaces do not dare to accept the certificates issued by their platforms. Even though the certificates are not recognized locally, students still want to continue learning on those online platforms.

Moreover, online educational platforms face significant hurdles when attempting to transition into formal education, particularly regarding accreditation. It found out that their certificates are not formally accredited as they are not registered in the formal education system of Myanmar, which is currently operating under the military regime that they are boycotting.

Many online education platforms attempt to expand by registering in other countries when it is not possible to register in Myanmar’s old educational system. However, this involves navigating different registration processes and legal requirements in each country, such as tax payments. This can be challenging for the platforms as they operate without making a profit and rely on donors and grants.

Additionally, three interviews highlighted the high cost of purchasing credits from international universities, ranging from $500 to $800 for just 3 credits. This financial burden makes it impractical for many students to afford these credits. Allocating significant funds to buy these credits would limit other educational investments, creating a tension between quantity and quality of educational programs. In response, educational platforms prioritize delivering high-quality education over expanding their course offerings. They focus on “Education in the heart,” emphasizing depth and impact of learning over the quantity of courses or credits offered.

Besides, partnership development is also a significant challenge for online educational platforms in Myanmar due to limitations in networking capabilities. Establishing meaningful partnerships, especially with international entities, is crucial for expanding educational offerings and enhancing credibility. The lack of extensive international connections restricts platforms’ ability to access critical resources, expertise, and recognition that could help obtain accreditation for educational programs.

Operational Capacity (Organization and System Structure and Adaptation to Local Context)

As Moore describes, operational capacity refers to an organization’s ability to utilize its resources to achieve its public value objectives effectively. In the context of Myanmar’s online educational platforms, the backbone of this adaptive operational capacity is the dedicated involvement of CDM teachers and volunteer staff. CDM teachers bring a wealth of academic expertise and a commitment to democratic values, enriching the educational content and fostering a deeper engagement with students. They leverage their professional networks to enhance course materials and integrate diverse perspectives through guest lectures. Moreover, the platforms rely heavily on the organizational and supportive efforts of volunteers who manage various administrative and educational tasks. These volunteers, many of whom are former students or educational professionals, are instrumental in maintaining the continuity and quality of education amid political instability.

Moreover, these online educational platforms are actively developing strategies to overcome challenges related to accreditation and recognition. Some initiatives include developing an internal credit system similar to the U.S. framework to standardize educational offerings. This move aims to align courses with international academic standards for better recognition and transferability.

Additionally, some online platforms are working with institutions like the University Interim Council, University of Yangon (UYUIC) to establish credit frameworks and transfer agreements for undergraduate students. This means that credits earned on one platform can be recognized and transferred to other educational institutions, making it easier for students to continue their education.

Some international universities offer scholarships for online courses and collaborate with local platforms to provide technical support. This collaboration reduces financial barriers for students and improves the quality of education available through these platforms.

As well, with the assistance of international universities, the University Interim Council, University of Yangon (UYUIC) has launched the Capstone project. This project is a collaboration between international universities and CDM teachers and is aimed at students with one semester left to graduate. It will start in September 2024 and will last 6 to 12 months, consisting of training, research, writing, defense, and publishing.

Therefore, it can be seen that these educational online platforms aim to address the existing gap. Meanwhile, undergraduate students frequently experience a lack of confidence without a university degree, which is considered crucial for career opportunities and social standing. The matter of accreditation is projected to become more pressing, especially for CDM students who depend on alternative platforms. Consequently, the National Unity Government of Myanmar needs to tackle these obstacles.

Policy Recommendations

Short-Term Recommendations (0-1 year)

- Create a single digital platform – NUG should create a single digital platform consolidating courses from various educational online platforms, covering a wide range of subjects. However, NUG’s role should be limited to creating the platform and combining the courses without interfering in the procedures and autonomy of the individual platforms.

- Digitalize essential curricular resources – To enhance the quality of distance learning materials, NUG should consider setting minimum standards and digitalizing vital curriculum resources, such as textbooks, for distance learning.

- Engaging Advocacy Entrepreneurs in Educational Implementation – The National Unity Government (NUG) needs to engage and support advocacy entrepreneurs in the field of education. These individuals will play a pivotal role in championing educational reforms and initiatives.

- Be transparent – The National Unity Government (NUG) must prioritize transparency in its educational initiatives. Clear communication of processes and developments will keep the public informed and prepared for upcoming changes.This openness will not only build trust but also foster a collaborative environment where all stakeholders can contribute to the educational progress of the nation.

Mid-Term Recommendations (1-2 years)

- Develop a Blockchain-Based Credentialing System – The National Unity Government (NUG) should collaborate with local and international tech partners to develop a blockchain-based system for issuing and verifying academic credentials. This system should be designed to integrate seamlessly with existing online educational platforms.

- Recognize and Promote the credit transfer framework the online platforms are implementing—NUG should recognize and promote the credit transfer system that the online platforms are implementing by partnering with other local educational platforms to be standardized.

- Supporting Existing Educational Alliance – Given the delays in the National Unity Government’s educational processes and the recent meeting to form an interim education council, the NUG should support the existing alliance of educational platforms rather than creating a new one. This approach will make better use of established resources and accelerate educational improvements.

- Government-to-Government Advocacy – NUG should establish diplomatic engagements with foreign governments to support and recognize Myanmar’s online educational platforms and formulate agreements that facilitate international collaborations and resource sharing.

Long-Term Recommendations (2+ years)

- Establish a Temporary Accreditation Body – Through the centralized platform and recognizing the educational online platforms’ alliance, NUG should establish a temporary accreditation body specifically designed to evaluate and certify online educational platforms. This body would operate with international standards in mind, ensuring that the courses offered are recognized both locally and internationally.

- Develop Strategic Partnerships with International Universities – The NUG should actively facilitate and endorse partnerships between Myanmar’s online educational platforms and reputable international universities. These partnerships could involve joint programs, credit transfers, and co-certification agreements, thereby enhancing the credibility and recognition of courses offered by Myanmar’s platforms.

- Integrate the WES Gateway Program– Like Ukraine, the National Unity Government (NUG) should partner with World Education Services (WES) to implement the WES Gateway Program for Myanmar. This program would assist students and professionals who have completed their studies through online platforms in Myanmar but are unable to obtain official documentation of their credentials due to the current political situation.

- Financial Support and Scholarships – The NUG could facilitate financial support mechanisms such as scholarships and grants for students and educational platforms. NUG’s budgets itself are likely to be tight. Therefore, the online learning system will need international assistance and support if it is to fulfil its reform objectives. This would alleviate some of the financial burdens associated with running online platforms and enable students from disadvantaged backgrounds to access these educational resources.

In conclusion, Myanmar’s education system is showing both strength and struggle during this tough time. The National Unity Government needs to focus on improving education by making sure all students and teachers have the support and safety they need. As Myanmar begins to develop a new education system, it is important to build one that is strong, flexible, and welcoming for everyone. With hard work and help from other countries, Myanmar can heal from the damage caused by the coup and create a better future for education.

References

- Antonivska, M. (2022). Russian-Ukrainian war: Challenges and perspectives for higher education. In Collection of Scientific Papers «SCIENTIA» (p. 163). November 25, 2022, Sydney, Australia.

- Bilyakovska, O., Horuk, N., & Karamanov, O. (2023). Ensuring the accessible educational environment under martial law: Results of the survey. Ivan Franko National University of Lviv.

- Brown, M. and N. Hung. 2022. “Higher Education in Myanmar.” In International Handbook on Education in South East Asia, edited by L. Pe Symaco and M. Hayden, 1–25. Singapore: Springer.

- CHEA (2010): The value of accreditation. Available at https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ValueofAccreditation.pdf.

- Chiu, Francesca (15 Apr 2024): Reclaiming the Future: Waiting, Resistance, and Expectations in Myanmar’s Post-Coup University Boycotts, Journal of Contemporary Asia, DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2024.2334261.

- Debone, D., Greenfield, D., Testa, L., Mumford, V., Higden, A., Pawley, M., Braithwaite, J. (2017). Understanding stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences of general practice accreditation. Health Policy, 121(7), 816–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.05.006.

- Faek, R. (2023, February 14). The War in Ukraine Raises New Questions About How Best to Support Affected Students. WENR. https://wenr.wes.org/2022/06/the-war-in-ukraine-raises-new-questions-about-how-best-to-support-affected-students.

- Frontier (2021), “Parents, Teachers, and Students Boycott ‘Slave Education System’”. Available at https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/parents-teachers-and-students-boycott-slave-education-system/.

- Goff, D., Johnston, J., & Bouboulis, B. (2020, February 6). Maintaining Academic Standards and Integrity in Online Business Courses. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(2), 248. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n2p248.

- Hong, M. and H. Kim. 2019. “‘Forgotten’ Democracy, Student Activism, and Higher Education in Myanmar: Past, Present, and Future.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20: 207–222. doi:10.1007/s12564- 019-09593-1.

- Htut, K. P., Lall, M., & Kandiko Howson, C. (2022, January 19). Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms? Education Sciences, 12(2), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020067.

- Kamibeppu, T., & Chao, Jr., R. Y. (2017, January 17). Higher Education and Myanmar’s Economic and Democratic Development. International Higher Education, 88, 19–20. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.88.9688.

- Khaing Phyu Htut, M. Lall, and C. Howson. 2022. “Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict— What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms?” Education Sciences 12 (67): 1–20.

- Lee, H., & Lee, M. J. (2021). Visual art education and social-emotional learning of students in rural Kenya. International Journal of Educational Research, 108, 101781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101781.

- Lopes, A., & Soares, F. (2022). Online distance learning course design and multimedia in E-learning. IGI Global.

- Londar, L., & Pietsch, M. (2023). PROVIDING DISTANCE EDUCATION DURING THE WAR: THE EXPERIENCE OF UKRAINE. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 98(6), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v98i6.5454.

- Ministry of Education, National Unity Government of Myanmar. (n.d.). Home page. Retrieved [May 2024], from https://moe.nugmyanmar.org/en/

- Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government. Harvard University Press.

- NBA (2019), National Board of Accreditation. Available at http://www.nbaind.org/accreditation.aspx.

- NUG. (September 2021). Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement. National Unity Government of Myanmar.

- OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT [Chatbot]. https://www.openai.com/chatgpt

- Proserpio, L., & Fiori, A. (2022, December 1). Myanmar universities in the post-coup era: The clash between old and new visions of higher education. T.wai. https://www.twai.it/articles/myanmar-universities-post-coup-era/#_ftn1.

- Radio Free Asia. (2024, January 8). Universities in Myanmar face sharp decline in enrollment. Radio Free Asia. https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/universities-01082024154241.html

- Reuters (2021). “More than 125,000 Myanmar teachers suspended for opposing coup”. Available at https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/more-than-125000-myanmar-teachers-suspended-opposing-coup-2021-05-23/.

- Sherman, M., Puhovskiy, E., Kambalova, Y., & Kdyrova, I. (2022). The future of distance education in war or the education of the future (the Ukrainian case study). Futurity Education, 2(3), 15-24. https://doi.org/10.57125/FED/2022.10.11.30.

- Spring University Myanmar. (2022, April 12). Hanging by a Thread: Education in Post-Coup Myanmar. Young Myanmar’s Scholars Commentary Series: Youth Perspective on Post-Coup Myanmar, Issue No.

- Spring University Myanmar, 2023. “Higher Education in Post Coup Myanmar”.

- Taylor, S. C., & Soares, L. (2020, February 24). Quality Assurance for the New Credentialing Market. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2020(189), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20398.

- Theobald, J., Gardner, F., & Long, N. (2017). Teaching Critical Reflection in Social Work Field Education. Journal of Social Work Education, 53(2), 300–311.

- Tun, A. (2022). The political economy of education in Myanmar: Recorrecting the past, redirecting the present, and reengaging the future. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

- UNHCR Regional Bureau for Europe. (2023, September). Education on hold: Addressing barriers to learning among refugee children and youth from Ukraine—challenges and recommendations. UNHCR.

- Verma, A. (2016). A review of quality assurance in higher education institutions. International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL), 44(5), 55–66.

- Williams, J. (2016). Quality assurance and quality enhancement: is there a relationship? Quality in Higher Education, 22(2), 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322. 2016.1227207.

- Yusoff, Z. M. (2017). Civil Disobedience: Concept and Practice. Asian Social Science, 129.

Download full paper: Click