Opportunities and Challenges of Scaling Up Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) in Thailand

Author: Nan Mwe Nohn

Advisor: Ora-orn Poocharoen

BACKGROUND

Violence against children (VAC) is a global public health issue with severe and costly consequences.

A systematic review found that over 1 billion children aged 2 to 17 experience some form of violence each year (Hillis et al., 2016). In low- and middle-income countries, including those in Africa and Asia, high rates of physical and psychological abuse persist (Stoltenborgh et al., 2013; Hillis et al., 2016; Alampay et al., 2018). The impacts of such abuse are profound, leading to long-term issues like self-harm, substance abuse, and mental health disorders (Hughes et al., 2017; Ramiro et al., 2010; Belsky and De Haan, 2011; Shonkoff and Fisher, 2013; Dunne et al., 2015). In Thailand, the prevalence of VAC is alarmingly high, with 57.6% of children experiencing sexual, physical, or psychological abuse (UNICEF, 2019). Despite the Child Protection Act of 2003, many parents remain unaware of the law, and physical punishment remains common, even though it is prohibited in schools (Watakakosol et al., 2019).

In a global context, to prevent the VAC and promote positive parenting, the Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) program was established in 2012 through a collaborative effort involving the World Health Organization, Stellenbosch University, the University of Cape Town, the universities of Oxford, Bangor, and Reading, and UNICEF (WHO, n.d.; Peace Culture Foundation, n.d.). The PLH-YC program is an in-person parenting program designed to help parents model positive behaviors for their children. Initially, it was a 12-session program in South Africa, but it was adapted to eight sessions for Thailand, focusing on parents of children aged 2-9 years.

The Peace Culture Foundation (PCF), an NGO based in Chiang Mai, has been expanding its Positive Parenting (PLH) training program in Thailand since 2018. The program was introduced in 2018 by Dr. Amalee McCoy, in collaboration with the University of Oxford, UNICEF Thailand, and the Thai Ministry of Public Health. It has been effective in reducing child maltreatment and promoting positive parenting. PCF has partnered with government public partners and Boromarajonani Nursing College to implement the program in administrative region 8 in Northeast Thailand. So far, 243 facilitators, 19 coaches, and 10 trainers have been trained to deliver the PLH-YC program, reaching over 1,100 parents in various provinces.

Furthermore, PCF is expanding its Positive Parenting (PLH) training program by collaborating with Boromarajonani Nursing College in Udon Thani. The program is aimed at nursing students and professionals, training them to become certified PLH-YC facilitators. This program is integrated into the Ministry of Public Health’s ChildShield System and utilizes health promotion hospitals to conduct sessions. By early 2024, 722 families had been trained, and PCF plans to train 840 families in 2024. The organization is also exploring digital services such as ‘ParentChat’ and ‘ParentText’ to broaden its reach. Additionally, PCF is establishing a Positive Parenting Promotion Center in Chiang Mai Province in partnership with the Department of Mental Health. The center will serve as a hub for capacity building and will offer evidence-based parenting programs across the northern region.

Objective, Research Questions, and Target Audiences of the Report

The report aims to investigate the possibilities and challenges of expanding the PLH-YC program within the Thai public health system. It provides an analysis to inform PCF and decision-makers about the best course of action to make the PLH-YC program relevant and accessible to as many families as possible in Thailand.

- What opportunities exist for scaling up PLH-YC in Thailand?

- What are the barriers or challenges to scaling up PLH-YC in Thailand? To address these questions?

The target audience for this report is PCF, members of the Global Parenting Initiative also aiming to scale up similar positive parenting programs in different parts of the world (e.g., Malaysia, the Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda), civil society organizations, UN agencies, and donors interested in exploring parenting program scale-up in their country contexts.

METHODOLOGY

Conceptual Framework Analysis

The study of the Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) initiative in Thailand applied two conceptual frameworks, the Futures Triangle and the 15 Factors Influencing Scaling Up. These frameworks were used to analyze the opportunities and barriers of scaling up.

- 15 Factors That Influence Scaling Up

The PLH-YC program’s scaling up is a complex process impacted by fifteen important variables. Raising awareness, involving stakeholders, and mobilizing resources all depend on advocacy. The scalability of the intervention is highly dependent on its attributes, such as relevance, efficacy, and flexibility. Cooperation between community people, governmental bodies, nearby charitable groups, and commercial sector establishments facilitates goal alignment and expedites endeavors (Edet, 2023). Wider access and integration into daily life are ensured through engagement mechanisms. At the same time, an external factor that causes natural catastrophes and unstable economies could affect the scaling-up process by offering crucial assistance.

However, there are several difficulties due to governance limitations including few funds and administrative roadblocks. The ability to implement the program with sufficient resources and knowledgeable staff is essential to maintaining program quality. Another crucial factor is political will and support are generated by stakeholders’ perceived need for engagement, while strong leadership provides clear direction to scale up the program’s plan. Moreover, another key is research and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems, by offer useful information for making well-informed decisions. For the program to be implemented effectively, safe resource availability, effective budgeting, and knowledge of the sociocultural context are essential. Finally, the secret to effective scaling is to take advantage of the correct opportunities during the “Window for Scale-up” (Edet, 2023)

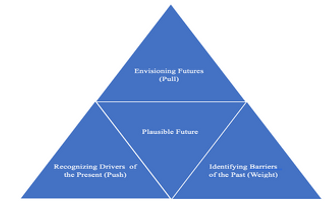

- Futures Triangles

The Futures Triangle, a strategic foresight tool developed by Sohail Inayatullah, evaluates the dynamics of change by examining three aspects: the pull of the past, the push of the present, and the pull of the future (Inayatullah, 2008). The pull of the future represents aspirational ideals and strategic objectives that guide policy, while the push of the present includes contemporary concerns and developments, such as demographic shifts and technological innovations, necessitating change. The weight of the past encompasses legacy, societal conventions, and institutional resistance to change. When drafting policies, this framework helps policymakers identify and analyze previous obstacles and current possibilities, taking sociocultural factors, inequality, and gender sensitivity into consideration (DPMC, 2021). By exploring various possible futures, policymakers can develop flexible and resilient policies for different circumstances while promoting mutual understanding of challenges and opportunities among diverse stakeholders (Future Platform, n.d.). Insights from the Futures Triangle support strategic and well-informed policy decisions (Sitra, n.d.).

- Qualitative Study on Scaling Up PLH-YC Program in Thailand

The research employed a qualitative method to delve into the intricacies surrounding the scaling up of the Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) program in Thailand. The data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, along with the retrieval of information from pertinent documents and websites. Dr. Ora-orn Poocharoen, an esteemed figure from Chiang Mai University, spearheaded the study, which involved the meticulous selection of participants by the Peace Culture Foundation (PCF). These chosen individuals possessed expertise in positive parenting programs and held extensive experience in pertinent ministries or organizations.

The research team invited 17 potential participants, out of the 17 identified participants, 14 were interviewed by Zoom. Each interview took a maximum of 1.5 hours for each interview with eight questions. These participants represented a diverse range of roles, including policymakers and representatives from Thailand’s social welfare and healthcare systems. This approach aimed to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. Ethical considerations were prioritized throughout the research process, with stringent measures in place to secure informed consent and protect the privacy of all involved parties.

The collected data was rigorously transcribed, translated, and subjected to analysis using the powerful MAXQDA software. By employing this advanced tool, the research team was able to identify key themes and patterns, offering valuable insights into the specific opportunities and challenges within Thailand’s context. However, it is important to note that broader financial and stakeholder interactions within the Public Health System were excluded from the study’s focus.

ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

Main Opportunities

The Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) program in Thailand showcases significant strengths that underline its potential impact and scalability.

- Strong Evidence-Based Success and Adaptability of the PLH-YC Program

Firstly, The PLH-YC program, validated by randomized control trials (RCTs), is one of the few evidence-based parenting initiatives in Thailand. Its customization for the Thai context and successful pilot in the Northeastern region enhances its credibility, cultural relevance, and efficacy. The program’s adaptability allows for nationwide implementation, making it a versatile tool for promoting positive parenting practices across Thailand.

- Cost-benefit Analysis

Furthermore, The PLH-YC program helps high-risk families break the cycle of violence and create safer environments for children. Supported by research, it provides policymakers with valuable insights through cost-benefit analyses and impact evaluations, like the Region 8 evaluation, to ensure the program’s effectiveness and optimization.

- Legislative Support

Next, Thailand has a strong legislative framework which includes the Child Protection Act of 2003 and the 5-Year National Plan. This framework supports the expansion of the PLH-YC program by ensuring the welfare of children. Additionally, the ‘Health in All Policies’ approach integrates health considerations into all sectors’ policies, thereby strengthening initiatives for child protection.

- Key Support and Initiatives for Expanding PLH-YC Program

The program is crucial to cooperation, and WHO and UNICEF are backing a national strategy and a National Early Development Policy Committee to ensure a coordinated approach. The existing initiatives, such as the Child Protection Joint Initiative, which includes PLH-YC, and the Ministry of Public Health’s readiness to pilot the program, provide a strong foundation for expansion.

- Collaboration and Capacity-Building Initiatives

Collaboration between the (PCF) and Boromarajonani Nursing College aims to establish a hub for positive parenting capacity-building. PCF’s efforts to create a Positive Parenting Promotion Centre in Chiang Mai and the Thai Positive Parenting Community of Practice further enhance stakeholder collaboration and integrate positive parenting into broader child protection strategies.

- Community-level Implementation Framework

Due to Thailand’s Health Promotion Hospitals and Village Health Volunteers form a robust framework for expanding PLH-YC, ensuring effective dissemination and implementation at the community level to reach more families and children.

- Political and Financial Support

Moreover, Thai engagement with supportive politicians can secure policies and funding for positive parenting programs. Additionally, funding sources like sub-district levels, the Department of Local Administration (DOLA), the National Health Security Office, the Thai Health Promotion Board, and government budgets provide financial resources for these programs.

- Enhancing Public Interest and Cultural Shifts

Finally, Enhancing the effectiveness and reach of the PLH-YC program is achievable by leveraging increasing public interest and shifting cultural values toward positive parenting. This strategy can be effectively scaled up to promote child well-being and protection across Thailand.

Main Challenges

Despite the opportunities, several key challenges need to be addressed to effectively scale up the Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) program in Thailand.

- Absence of a Coherent National Policy

There is a significant gap in having a coherent national policy or strategy to support positive parenting and child protection systems. This leads to fragmented efforts, a lack of policy directives, and insufficient budget allocations, hindering the scaling of such programs.

- Lack of Clear Leadership

The absence of clear leadership for the scaling-up plan results in fragmented efforts and reduced efficiency. Effective implementation requires a dedicated entity to lead and coordinate across sectors.

- Mandate Separation

The Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) does not have a primary mandate for child protection, which falls under the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security (MSDHS). This causes gaps in coordination and implementation. Enhanced collaboration between MOPH and MSDHS is needed.

- Role of MOI and DOLA

The Ministry of Interior (MOI) and the Department of Local Administration (DOLA) manage numerous health facilities and child centers, but child protection and parenting support are not within their mandates. Expanding their roles requires strategic planning and reallocation of responsibilities.

- Implementation Process Design

Designing an effective implementation process involves creating incentives for facilitators, developing a comprehensive caregiver recruitment process, and establishing thorough monitoring and evaluation systems for pilot programs.

- Resource-Intensive Nature

The resource-intensive nature of the PLH-YC program demands significant financial, human, and logistical resources, presenting barriers to scaling, especially in resource-limited regions. Long-term commitment from various agencies and organizations is crucial.

- Organizational Capacity

The Peace Culture Foundation (PCF) faces limitations in its capacity to lead the scaling-up effort. Strengthening PCF through additional resources, funding, training, and partnerships is essential for effective scaling and sustainability.

- Public Awareness and Support

The lack of public awareness and support for children’s rights to protection is a significant issue. Raising awareness through campaigns, education, and advocacy is necessary to build a supportive environment for child protection and positive parenting.

- Generating Demand

Generating demand from parents, caregivers, and service providers is crucial for the success of programs like PLH-YC. Engaging and educating these groups and demonstrating the benefits of positive parenting can help increase demand and support for the program.

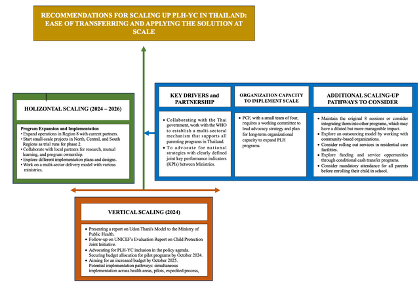

Conclusion and Recommendations

To effectively expand the Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children (PLH-YC) program in Thailand, a strategic plan involving both vertical and horizontal scaling is required. This strategy focuses on identifying key drivers, forming effective partnerships, and enhancing organizational capacity to ensure the program’s transfer and application across different regions. The main goal is to integrate PLH-YC into the national health agenda for widespread and sustainable implementation. To achieve this, evidence-based models will be presented to secure government support, pilot programs will be conducted, and various pathways for sustainable expansion will be explored. Coordinated efforts from multiple ministries and international organizations are essential to making PLH-YC a cornerstone of child health and welfare across Thailand. Moreover, following recommendations that ease of transferring and applying the solution, there was a successful scale-up of the PLH-YC program in Thailand.

- Vertical Scaling Up by 2024

To effectively scale up the PLH-YC program, several strategic steps need to be implemented starting in 2024.

The initial actions include preparing and presenting a comprehensive report on the Model of Udon Thani or Region 8 to the Ministry of Public Health. Following this, it is crucial to follow up with the Ministry on the Evaluation Report of the Child Protection Joint Initiative (2018-2022) conducted by UNICEF. These steps are fundamental in advocating for the inclusion of PLH-YC on the policy agenda of the Ministry or related Ministries.

The following phase involves securing budget allocations for pilot programs in other regions by October 2024 and gaining support from high-level decision-makers within the Ministry. The ultimate objective is to secure an increased budget allocation by October 2025, ensuring the program’s sustainability and wider implementation.

There are three potential steps for implementing the PLH-YC program:

- Simultaneous Implementation Across All Health Areas: This approach entails requesting all health areas to implement the program simultaneously, ensuring consistent adoption and potentially expediting the scaling process.

- Piloting and Adaptation Before Full Implementation: This pathway involves conducting pilot programs in different regions, making necessary adaptations based on the outcomes, and subsequently implementing the program in its entirety. This method allows for refining the program to better suit local contexts before widespread adoption.

- Expedited Process with Political Support: This approach focuses on obtaining expedited support from the Minister and their political team. By securing high-level political backing, the implementation process can be accelerated, leveraging political will and resources.

Moreover, a critical decision is how to position the PLH-YC program, either as part of the Child Protection System or as a Parenting Support System, which will significantly impact its implementation and overall effectiveness.

- Horizontal Scaling Up for 2024-2026

- Extend Operations for 2024–2026

The program aims to expand the reach and effectiveness of PLH-YC from 2024 to 2026.

- Expand Partnerships in Region 8

The program needs to focus on collaborating with regional partners like Boromarajonani Nursing College to establish a regional capacity-building hub. Region 8, which has shown promising results, will serve as a model for future growth.

- Conduct Small-Scale Initiatives

To test and enhance the program for broader adoption, small-scale pilot projects are being carried out in Thailand’s North, Central, and South areas.

- Explore Implementation Plans

We will continuously explore alternative implementation strategies, such as diversifying funding sources and improving the family selection procedures.

- Drivers, Enabling Conditions, and Partnerships

The success of the PLH-YC program in Thailand relies on key elements such as influential individuals, favorable conditions, and strategic partnerships. It is essential to have a strong collaboration with the Thai government to align national policies and secure funding and support for parenting programs. Collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) helps in establishing a comprehensive framework to bolster parenting initiatives across Thailand. Additionally, promoting national policies with clearly defined key performance indicators (KPIs) shared by multiple ministries ensures cohesive efforts, leading to improved efficacy of child protection and parenting programs.

- Organizational Capacity to Implement the Solution at Scale-Up

Despite the ambitious goals of the Peaceful Children Foundation (PCF), it currently operates with a small team of only five individuals. To effectively drive their advocacy strategy and execute the Scaling-up Plan with all its partners, it is crucial to establish a dedicated working committee. This committee would play a pivotal role in coordinating efforts, managing resources, and ensuring alignment among all stakeholders. Additionally, PCF must plan for the long-term organizational capacity needed to scale the PLH programs efficiently. This entails not only expanding the team but also developing the necessary infrastructure and processes to support the program’s expansion and sustainability. By addressing these capacity challenges, PCF can ensure that the PLH-YC program influences more families and children, maximizing its impact on child protection and positive parenting in Thailand.

- Additional Practical Processes for Scaling-Up Pathways

Various tactics are to be taken into consideration to enhance the efficacy and execution of the PLH-YC program in Thailand.

- First, the effectiveness and comprehensiveness of the PLH-YC program may be ensured by continuing with its original eight sessions. As an alternative, including these sessions within already-existing family programs could simplify participation by removing the need for extra time commitments, although it might slightly change the focus of the material.

- Moreover, a further successful tactic is to form alliances with local groups. These organizations may assist in delivering the PLH-YC program, reaching more participants and assuring more families benefit from its interventions because of its well-established presence and trusted standing in the community.

- It’s also essential to offer services in residential care settings. provide them with the materials and assistance they need to encourage positive parenting practices and child development, this program specifically targets vulnerable children and families.

- Next, the PLH-YC program can have a stable financial base by taking into account financing and service opportunities through conditional cash transfer programs. These initiatives provide families cash rewards for carrying out certain behaviors, such as showing up to parenting classes, raising participation rates, and sustaining steady involvement.

- Finally, requiring parents to enroll in the PLH-YC program before their child’s school entry can guarantee complete involvement and optimize the advantages. By ensuring that all parents receive the training they need to raise resilient and healthy kids, this strategy promotes consistent parenting techniques and closes the achievement gap. Making this a regular requirement can increase the efficacy and reach a wider audience, improving children’s future achievement and general well-being.

In conclusion, the recommendations for scaling up the PLH-YC program in Thailand highlight the need for strategic planning, robust partnerships, and comprehensive support systems. By leveraging existing opportunities and addressing challenges, the program can achieve widespread implementation and significantly enhance child protection and positive parenting practices across Thailand.

References

[1] Alampay, L.P., Lachman, J.M., Landoy, B.V., Madrid, B.J., Ward, C.L., and Hutchings, J. (2018). Preventing child maltreatment in low- and middle-income countries: Parenting for Lifelong Health in the Philippines. In: Verma S, Petersen C, editors. Developmental science and sustainable development goals for children and youth, social indicators research series 74. p. 277–93.

[2] Belsky, J., & De Haan, M. (2011). Annual research review: Parenting and children’s brain development: The end of the beginning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(4), 409-428.

[3] Dunne, M., Choo, W. Y., Madrid, B., Subrahmanian, R., Rumble, L., Blight, S., & Maternowska, M. C. (2015). Violence against children in the Asia Pacific region: The situation is becoming clearer. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(8S), 6S–8S..

[4] Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC). (2021). Futures thinking and the policy process. Retrieved from https://www.dpmc.govt.nz/our-programmes/policy-project/policy-methods-toolbox/futures-thinking .

[5] Edet, R. (2023). A review of frameworks and tools for scaling up social interventions (pp.26-47). School of Public Policy, Chiang Mai University. Retrieved from https://spp.cmu.ac.th/a-review-of-frameworks-and-tools-for-scaling-up-social-interventions/

[6] Futures Platform. (n.d.). How Can We Anticipate Plausible Futures? Retrieved from https://www.futuresplatform.com/blog/how-can-we-predict-plausible-futures

[7] Fry, D., McCoy, A., & Swales, D. (2012). The consequences of maltreatment on children’s lives: a systematic review of data from the East Asia and Pacific Region. Trauma Violence Abuse, 13(4), 209-233. doi:10.1177/1524838012455873

[8] Global Parenting Initiative. (2022). Parenting within the public health system in Thailand: Updates. Retrieved from https://globalparenting.org/parenting-within-the-public-health-system-in-thailand-updates#collapse4219981*

[9] Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079.

[10] Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., . . . Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356-e366. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(17)30118-4

[11] Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: futures thinking for transforming. Foresight, 10(1), 4- 21. Retrieved from https://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/sobipro/55/760-six-pillars-futures-thinking-for-transforming .

[12] Jongudomsuk, P., et al. (2015). The Kingdom of Thailand health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 5(5), 1-228. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/208216/9789290617136_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y .

[13] Manzoni, P., & Schwarzenegger, C. (2019). The influence of earlier parental violence on juvenile delinquency: The role of social bonds, self-control, delinquent peer association and moral values as mediators. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 25(3), 225-239.

[14] Milat, A. J., King, L., Bauman, A. E., & Redman, S. (2013). The concept of scalability: increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health promotion international, 28(3), 285-298.

[15] Ministry of Social Development and Human Security. http://www.m-society.go.th

[16] Ministry of Public Health, Thailand. http://www.moph.go.th

[17] National Health Security Office (NHSO). https://eng.nhso.go.th/view/1/Home

[18] Niu, H., Liu, L., & Wang, M. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of harsh discipline: The moderating role of parenting stress and parent gender. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 1–10.

[19] Peaceful Foundation. (2021). Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children in Thailand. Retrieved from https://www.peaceculturefoundation.org/background-parenting-for-lifelong-health

[20] Ramiro, L., Madrid, B., & Brown, D. (2010). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 842–855.

[21] Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical psychology review, 34(4), 337-357.

[22] Sanders, M.R., Divan, G., Singhal, M. et al. (2022) Scaling Up Parenting Interventions is Critical for Attaining the Sustainable Development Goals. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 53, 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01171-0

[23] Shonkoff, J. P., & Fisher, P. A. (2013). Rethinking evidence-based practice and two-generation programs to create the future of early childhood policy. Development and psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1635-1653.

[24] Simmons, R., & Shiffman, J. (2007). Scaling up health service innovations: a framework for action. Scaling up health service delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1-30.

[25] Sitra. (n.d.). The Futures Triangle. Retrieved from https://www.sitra.fi/en/cases/the-futures-triangle/

[26] Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., and van IJzendoorn, M.J. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: a meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, volume 48, pages 345–355.

[27] Tangcharoensathien, V., Witthayapipopsakul, W., Panichkriangkrai, W., Patcharanarumol, W., & Mills, A. (2018). Health systems development in Thailand: a solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet, 391(10126), 1205–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30198-3

[28] UNICEF. (2019). Thailand Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. National Statistical Office Thailand.

[29] United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) – Thailand (2023). https://www.unicef.org/thailand

[30] Ubin, P., Jain, P. S., & Brown, L. D. (2000). Think large and act small: Toward a new paradigm for NGO scaling up. World Development, 28(8), 1409-1419.

[31] Ward, C., Sanders, M. R., Gardner, F., Mikton, C., & Dawes, A. (2016). Preventing child maltreatment in low- and middle-income countries: Parent support programs have the potential to buffer the effects of poverty. Child Abuse Negl, 54, 97-107. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.11.002

[32] Watakakosol, R., Suttiwan, P., Wongcharee, H., Kish, A., & Newcombe, P. A. (2019). Parent discipline in Thailand: corporal punishment use and associations with myths and psychological outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 298-306.

[33] World Health Organization. (n.d.). Child maltreatment. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/parenting-for-lifelong-health/young-children

[34] World Health Organization (2023). WHO Thailand. https://www.who.int/thailand

Download full paper: Click