A Critical Policy Analysis of Myanmar University Admission: Conflict and Access to Higher Education

Author: Sa Phyo Arkar Myo Hlaing

Advisor: Asst. Prof. Pobsook Chamchong, PhD

1. Executive Summary

The expansion of access to higher education in Myanmar between 2011 and 2021 has raised questions about equity in its recurring conflict context. This qualitative documentary analysis indicates that conflicts led to the maldistribution of resources caused by the closures of schools and examination centres and to cultural injustices arising from standardising the Burmese language and rigid citizenship requirements in education. The disparity of representation in university admission policy emanates from these conflicts, while the peace-building perspective of admission is often overlooked. This study recommends incorporating four crucial dimensions, namely redistribution, recognition, representation and reconciliation, into the university admission policy in post-conflict Myanmar to promote transformative social change.

2. A Problematic University Admission Policy

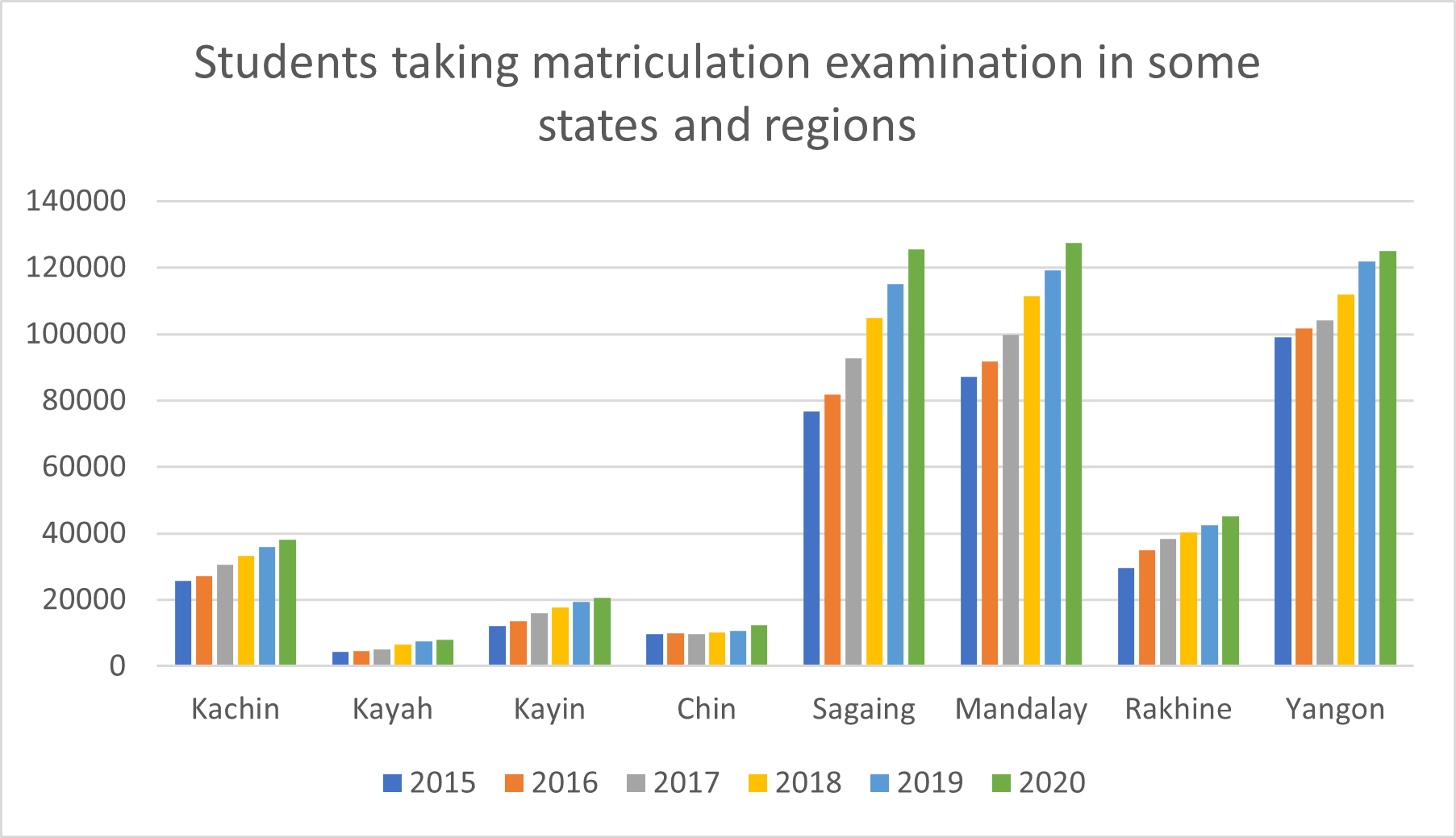

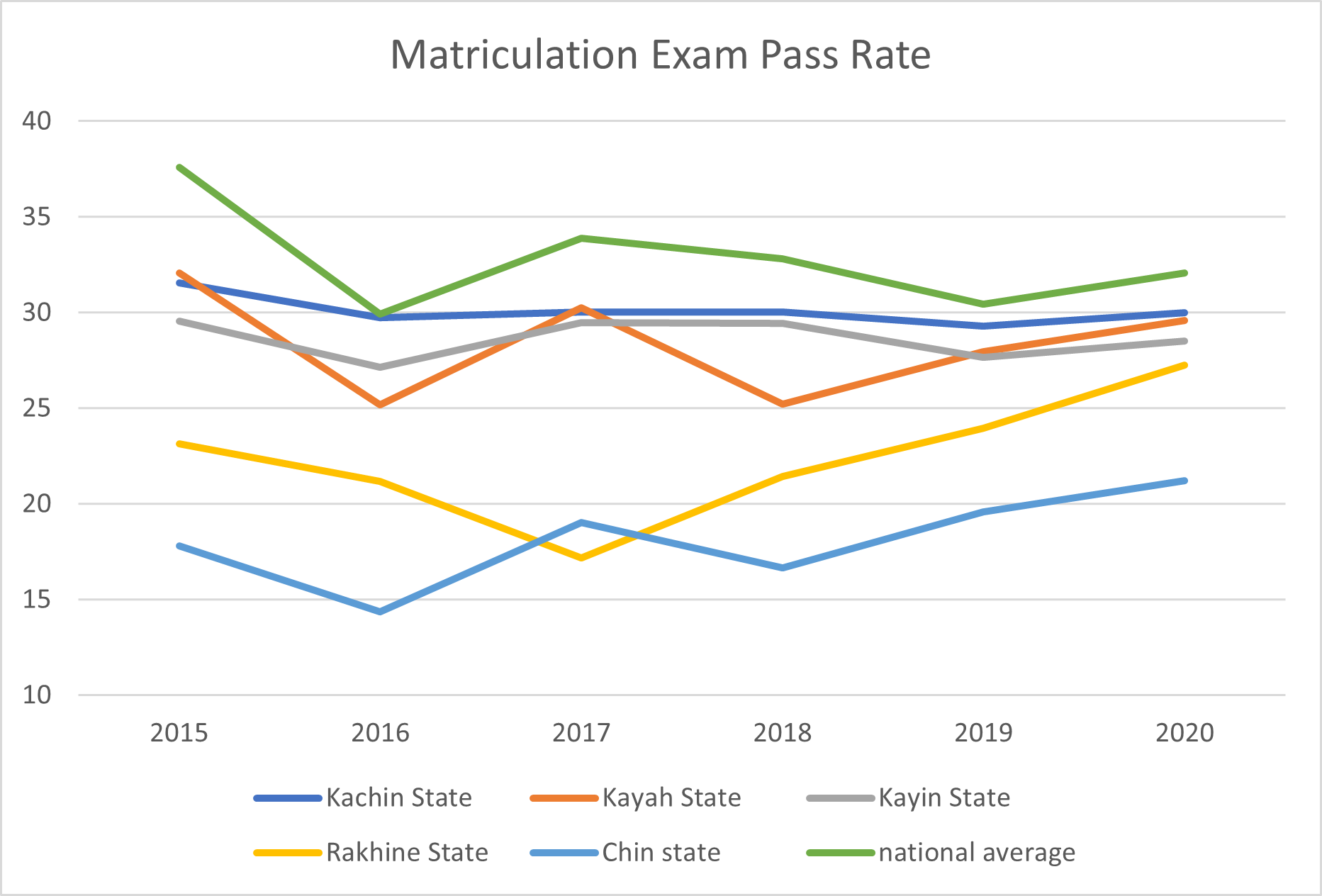

The current university admission policy in Myanmar[1] is arguably not equitable and contributes to the cultural injustice that spurs ongoing conflict within Myanmar. Between 2011 and 2021, the transitions in Myanmar set education reform as a priority (Lall, 2020). As the budget was increased ninefold, the number of students taking the matriculation examination – a stand-alone university admission criterion, increased from approximately 0.6 million in 2015 to 0.9 million in 2020, expanding access to higher education (Ministry of Education, 2020). Despite this expansion, there are questions about equity. Students in ethnic areas, long affected by conflicts and poverty, tend to have less access to and perform poorly in the exam (see Fig 1& 2). Moreover, other conditions such as the requirement of citizenship identification have led to the lower enrolment of higher education among students in conflict-affected areas.

Figure 1 Comparison of students’ access to matriculation examination in some states (conflict-affected) and regions

Source: author’s calculation based on MOE release

Figure 2 Comparison of matriculation examination pass rate in some (conflict-affected) states of Myanmar with the national average

Source: author’s calculation based on MOE release

Higher education is a key determinant of a person’s social, economic and political participation. While people without exam pass certificates have no access to higher education and limited employment opportunities, those who earn higher marks in the exam not only enter the universities but also earn greater social, economic and political benefits later in life. As Jia & Ericson (2017) argue, this high-stakes exam-based university admission validates the existing structure, naturalises social and economic stratification, and exacerbates disparities. Particularly in Myanmar, where conflicts emanate in structural exclusion, the university admission policy tends to exacerbate already-widening disparities caused by conflicts, and create grievances, contributing to recurring conflicts (Higgins et al., 2016; Lall, 2020). Therefore, it is relevant to re-evaluate the relevancy of the current university admission policy in Myanmar through a wider structural approach.

3. Finding and analysis

This section provides an analysis and discussion of the experiences of students in the conflict-affected area within the existing university admission policy.

Redistribution: Economic Justice in University Admission

In Myanmar’s university admission context, the conflict has led to a maldistribution of resources through a direct violence against schooling. It has affected students’ learning and their performance in matriculation examinations. Due to the conflicts in Northern Rakhine[2], more than 1,000 students including those preparing for the matriculation exam could not attend schools, and in Paletwa Township of Chin State, a neighbouring territory of northern Rakhine, 191 out of 384 schools were closed, and over 200 teachers applied for transfer to other territories (Khai, 2022; Myint, 2019). Furthermore, the conflict proliferates numerous internally displaced communities living in camps, where schools have to be re-established and often lack basic resources and teachers. For example, fierce battles between the Myanmar military and KIA[3] in 2012 displaced more than 12,0000 people, including school-age children, causing them to reside in IDP camps for several years (Bawk La, 2017; Myint, 2019).

Conflicts also caused the reduction of matriculation exam centres, incurring more economic obstacles to the family and affecting students’ performance in education achievement. In 2020, 20 examination centres in Rakhine, accommodating more than 6,000 students, were closed and merged with test centres in urban areas before the examination period (BBC News မြန်မာ, 2020a). This incurs more economic burden on students and their families, including increased costs on transportation and accommodation during the two-week exam period as the government provides no logistical support. As a result, more than 4,000 exam-registered students in Rakhine State were absent from the 2020 exam (BBC News မြန်မာ, 2020b).

The long-lasting impact of conflicts deteriorates the economic prosperity of the individual family, leading to reduced investment in education, dropouts and less access to higher education (Darwish & Wotipka, 2022). Research reveals that, in the matriculation examination, the most affluent townships perform best while significantly a smaller number of students took it in the least affluent townships, and the poorest states such as Chin and Rakhine States have the lowest pass rates with an average of 16% and 21% respectively from 2012 to 2019 (Stenning, 2019).

Recognition: Cultural Justice in University Admission

The university admission policy and the wider education system contribute to cultural injustice through the standardised use of the Burmese language, which negatively affects higher education access for ethnic students, who often reside in remote and conflict-affected areas. This impact manifests in both immediate and long-term ways. In the immediate sense, ethnic students who do not speak Burmese fluently tend to perform poorly in the Myanmar Reader subject of the matriculation examination than their Burmar peers, resulting in lower overall marks and positioning them at a disadvantage within the education system (Stenning, 2019; Suante, 2022).

Secondly, in a long-term manner, the sole use of Burmese as the medium of instruction hampers ethnic students’ access to higher education. Children from ethnic minority groups, particularly those from remote and conflict-affected areas, read and write Burmese at a slower pace than their Burmar counterparts because it is their second (if not third) language, and tend to achieve significantly lower performance in reading, writing, and mathematics, resulting in poor confidence and dropping out of schools (Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), 2019; Lall, 2020; Salem-Gervais & Raynaud, 2020; Stenning, 2019). Even if they retain until secondary school, they tend to earn poorer total marks in the matriculation examination because the language of assessment is either Burmese (in arts subjects) or English (in science subjects) (Lall, 2020).

In fact, the conflicts in Myanmar originated from cultural injustice, the absence of the recognition of ethnic cultures and languages (Fraser, 2008; Higgins et al., 2016; Lall, 2020; Salem-Gervais & Raynaud, 2020). This has fuelled ethnic insurgencies aimed at preserving cultural identity (Suante, 2022). In other words, the sole use of Burmese in education perpetuates cultural injustice and creates conditions for the reproduction of future cultural injustice, causing more conflicts. Importantly, students in conflict-affected areas often belong to ethnic groups and so face the compounded disadvantages of conflicts and language barriers (Lall, 2020).

The rigid citizenship status requirement in applying for universities also reinforces cultural injustice, negatively impacting students in conflict-affected areas. Almost all the universities in Myanmar mandate that applicants hold citizenship status in accordance with the existing 1982 Citizenship Law which stipulates that only those who can prove that their ancestors resided in Myanmar before 1824 shall be granted citizenship[4] (Lwin, 2000; Stenning, 2019; တက္ကသိုလ် ဝင်ခွင့်လမ်းညွှန် , ၂၀၂၀; မြန်မာနိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေ, ၁၉၈၂). This practice is discriminatory against students in conflict-affected areas, particularly Rohingya[5], who often lack those documentation, therefore de facto stateless and unable to apply to university or access certain jobs. This exclusionary practice limits upward social mobility and fosters grievances, further perpetuating conflicts.

Representation: Political Justice in University Admission

The university administration, including student recruitment, is highly centralised and bureaucratic, resulting in the disparity of participation (Lall, 2020). Since the 1962 coup de ‘tat, Myanmar universities have been administered by the national-level administrative body and the admission was solely based on the total marks obtained in the matriculation examination[6] so that highly-performed students could be allocated to science streams in accordance with the science-superior education policy of the regime (၁၉၆၄ခုနှစ်၊ပြည်ထောင်စုမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေးဥပဒေ, ၁၉၆၄; Lall, 2020; Lwin, 2000). In other words, the university admission policy was formulated neither by parity of participation nor by considering equitable principle, neglecting the country’s prevailing conflict context. Studies argue that these developments closely tie with conflicts, particularly campus activism as it was driven by regime’s political agenda to control university students who play a critical role in social movements (Heslop, 2019; Lall, 2020).

The necessity of achieving parity of participation in the university governance and its subset admission policy is evident in the 2015 student uprising, which urged for the inclusion of teachers and students in education policy development, including university admission policy (Heslop, 2019). Although National Education Law (2014) pledged for the university autonomy and the reforms of the university admission to be based on students’ preference and principles of the individual university, the following policy reforms have predominantly been implemented in a top-down manner, and the lack of parity of participation in the policymaking remains prevalent.

Reconciliation: Peace Building Perspectives in University Admission

Peacebuilding perspectives are often overlooked in the matriculation examination. According to interviews conducted by Heslop (2019), higher education personnel in Myanmar consider the practice of admitting students based on matriculation examination results as equitable by citing its national standardisation and reasonable cost. However, this attitude fails to acknowledge the disparities caused by socioeconomic backgrounds, the impact of conflicts, language, citizenship and so on.

Reconciliation is often associated with ensuring the presence of diverse groups in admission. Although Myanmar has made some progress in this regard through admission reforms by considering the university application of ethnic students with special preference on matriculation scores and by establishing more universities in ethnic areas, it is rather driven by the human capital ideology of NESP[7] and historically, by the regime’s political agenda to suppress down campus activism by separating students and weakening social movement (Asia-Europe Foundation, 2021; Heslop, 2019; Lall, 2020; Tun, 2022).

All in all, in the conflict context of Myanmar, the university admission policy led to social injustice through disparity in redistribution, recognition and representation while reconciliation, the peacebuilding aspect, is often overlooked.

4. Policy Recommendations

To promote peace in post-conflict Myanmar, it is crucial to ensure the presence of redistribution, recognition, representation, and reconciliation in university admission policy.

Redistribution

- The government should subsidise students in conflict-affected areas: In addition to the allocated education budget, subsidies should be provided to support these students, along with psycho-social support, securing related costs incurred by the migration and closure of matriculation examination centres.

- Education budget allocation criteria should consider the conflict situation: The bureaucratic and implemental practices of budgeting in Myanmar education should be modified to ensure equitable supports, reflecting the country’s conflict context.

Recognition

- Special consideration should be given to ethnic students from conflict-affected areas in university admission in addition to matriculation examination results: Special consideration, such as lowering the total marks, should be given to ethnic students’ university admission applications, especially those applying for professional and prestigious institutions.

- Mother Tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) should be adopted in the Myanmar education system. In the MTB-MLE system, the mother tongue of the children is initially used as the medium of instruction in primary education before shifting into national and international languages. Studies have shown that it increases access to education and recognises the culture of specific ethnic groups and, thereafter, has the potential to promote sustainable peace in Myanmar (Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), 2019; Salem-Gervais & Raynaud, 2020; South & Lall, 2016, 2016).

- The rigid citizenship requirement in university application should be relaxed: The right to education should not be undermined by citizenship law. Therefore, Myanmar universities should consider those students from conflict-affected areas, particularly Rohingya, with special consideration for citizenship requirements.

Representation

- Participation should be promoted in the education policy process, including university admission policy: The parity of participation of relevant stakeholders such as university personnel, students/teachers’ union and ethnic education stakeholders who provide education in conflict-affected areas, should be ensured through the use of deliberative participatory policy framework tools.

Reconciliation

- The university admission policy should promote diversity and reflect the historical experiences of Myanmar society. Admission practices have the potential to contribute to peacebuilding by ensuring diversity and providing opportunities for those who have been historically disadvantaged in the country. For example, the adoption of a quota system could be considered.

In conclusion, the dimensions of the 4’R framework are interrelated with each other and therefore should be considered together to address the exclusionary practices in the Myanmar university admission (Fraser, 2008; Heslop, 2019; Novelli et al., 2017).

5. References

- ၁၉၆၄ခုနှစ်၊ပြည်ထောင်စုမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတက္ကသိုလ်ပညာရေးဥပဒေ. (၁၉၆၄). ပြည်ထောင်စုမြန်မာနိုင်ငံ တော်လှန်ရေး ကောင်စီ. http://constitutionaltribunal.gov.mm/lawdatabase/my/law/758

- Asia-Europe Foundation. (2021). National Higher Education Equity Policy, Myanmar. 8th ASEF Regional Conference on Higher Education (ARC8) on “Inclusive and Diverse Higher Education in Asia and Europe”. https://worldaccesshe.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MYANMAR_HE-Equity-Policy_2021_ARC8-1.pdf

- Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). (2019). Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics 2019 National Report of Myanmar. https://www.seaplm.org/images/Publication/Myanmar_Report/SEA-PLM_2019_National_Results_-_Myanmar_report_English.pdf

- Bawk La, H. (2017). | A study of Ethnic Kachin Students (from Kachin Independence Organization-controlled areas) in the current Myanmar Education system.

- BBC News မြန်မာ. (2020a). ရခိုင်စာစစ်ဌာန ၂၀ ပိတ်လို့ ကျောင်းသားထောင်ချီ နေရာပြောင်းဖြေရမယ်. BBC News မြန်မာ. https://www.bbc.com/burmese/burma-51506554

- BBC News မြန်မာ. (2020b). ရခိုင်မှာ ကျောင်းသား လေးထောင်ကျော် တက္ကသိုလ်ဝင်တန်းစာမေးပွဲ လာမဖြေ. BBC News မြန်မာ. https://www.bbc.com/burmese/burma-51838167

- Darwish, S., & Wotipka, C. M. (2022). Armed conflict, student achievement, and access to higher education by gender in Afghanistan, 2014–2019. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2115340

- Fraser, N. (2008). Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World. Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, 36, 11–39. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-64452009000200001

- Heslop, L. (2019). Encountering internationalisation: Higher education and social justice in Myanmar [Doctoral, University of Sussex]. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/87242/

- Higgins, S., Maber, E., Lopes Cardozo, M., & Shah, R. (2016). The role of education in Peacebuilding Country Report: Myanmar. University of Amsterdam. https://educationanddevelopment.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/myanmar-country-report-executive-summary-final-jun16.pdf

- Jia, Q., & Ericson, D. P. (2017). Equity and access to higher education in China: Lessons from Hunan province for university admissions policy. International Journal of Educational Development, 52, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.10.011

- Khai, K. S. (2022). Evaluation of the Equality of Education on Basic Education Standard in Chin State, Burma/Myanmar | SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-6675-9_4

- Lall, M. (2020). Myanmar’s Education Reforms: A pathway to social justice? In UCL Press: London. (2020) (pp. ix–297). UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787353695

- Lwin, T. (2000). Education in Burma (1945-2000), 2000 | PDF | Myanmar | Secondary School. https://www.scribd.com/document/258239545/1-Education-in-Burma-1945-2000-2000

- Ministry of Education. (2020, September 18). နိုင်ငံတော်အစိုးရ၏ (၄)နှစ်တာကာလအတွင်း ပညာရေးပြုပြင်ပြောင်းလဲမှု ဆောင်ရွက်ချက်များ. ပညာရေးဝန်ကြီးဌာန. http://www.moe.gov.mm

- Myint, M. (2019). Civilian-Led Programs the Answer for IDP Students in War-Torn Rakhine. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/civilian-led-programs-the-answer-for-idp-students-in-war-torn-rakhine.html

- National Education Law. (2014). Myanmar—National Education Law, 2014 (41/2014). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=100493

- Novelli, M., Lopes Cardozo, M. T. A., & Smith, A. (2017). The 4Rs framework: Analyzing education’s contribution to sustainable peacebuilding with social justice in conflict-affected contexts. Journal on Education in Emergencies, 3(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.17609/N8S94K

- Salem-Gervais, N., & Raynaud, M. (2020). Teaching ethinic minortity languages in government schools and developing the local curriculum. Yangon: Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung Ltd., Myanmar. Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung Ltd., Myanmar.

- South, A., & Lall, M. (2016). Schooling and Conflict: Ethnic Education and Mother Tongue-based Teaching in Myanmar – NUS Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS). https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/books/schooling-and-conflict-ethnic-education-and-mother-tongue-based-teaching-in-myanmar/

- Stenning, E. (2019). Inception study on Assessment and Examination Experiences for Marginalised Groups [Inception Report Vol 2.].

- Suante, K. T. T. (2022). The history and politics of schooling in Myanmar: Paedagogica Historica: Vol 0, No 0. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00309230.2022.2073181

- Tun, A. (2022). The Political Economy of Education in Myanmar: Recorrecting the Past, Redirecting the Present and Reengaging the Future. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ISEAS_EWP_2022-5_Aung_Tun.pdf#:~:text=Myanmar%E2%80%99s%20education%20sector%20has%20been%20consistently%20starved%20of,and%20on%20educated%20Myanmar%20migrants%20in%20the%20diaspora.

- တက္ကသိုလ် ဝင်ခွင့်လမ်းညွှန် (၂၀၂၀ ပြည့်နှစ်၊ တက္ကသိုလ်ဝင်ခွင့် စာမေးပွဲ အောင်မြင်သူများ အတွက်). (၂၀၂၀). တက္ကသိုလ်ဝင်ခွင့် စိစစ်ရွေးချယ်ရေးအဖွဲ့၊ အဆင့်မြင့်ပညာဦးစီးဌာန၊ ပညာရေးဝန်ကြီးဌာန၊ ပြည်ထောင်စုသမ္မတမြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော် အစိုးရ.

- မြန်မာနိုင်ငံသားဥပဒေ. (၁၉၈၂). https://constitutionaltribunal.gov.mm/lawdatabase/my/law/1015

Note:

[1] “Myanmar” is a contested term. While it was officially adopted by the military regime in 1989, some still refer to the country as Burma, opposing military legitimacy. In this study, the term “Myanmar” is used to refer to the country while Bamar is employed for indicating the largest ethnic group in the country. Burmese is the language of Bamar and the sole official language of the state.

[2] The conflicts in northern Rakhine between 2019 and 2021 were due to the armed confrontation between the Myanmar Military and the Arakan Army, and the military extensive clearance operation toward the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army.

[3] Kachin Independence Army

[4] According to the yearly-published university admission guidelines, there are only a few universities which do not set the citizenship status as one of the criteria. For instance, the University of Distance Education – a type of open university in Myanmar yet low-ranked, does not specify citizenship status for most of the specialisations with the exception of law, economics and business administration majors.

[5] Since 2012 inter-religious tension, Rohingya students have been prohibited from studying at university partially because the government could not guarantee their security. In 2022, the restrictions were lifted, and they were allowed to enrol at Sittwe University, Rakhine State.

[6] Starting from 2018 AY, the university-administered admission practices were piloted at 11 selected universities. In addition, there are also some universities which are not under the Ministry of Education such as University of the Development of the National Races and practice their admission policy separately.

[7] National Education Strategic Plan (2016-2021)

Download full article >>> Click