Enhancing Municipal Engagement: Town Hall Meeting Initiatives in Myanmar

Author: Yamin Oo

Advisor: Asst. Prof. Pobsook Chamchong, PhD

Problem Statement

Citizen participation is crucial in democratic politics as it ensures government decisions align with the consent of the governed. Citizen participation goes beyond democracy alone; it also contributes to legitimizing policy development and implementation (Fischer, 2003). Town hall meetings provide an open platform for citizens to engage in discussions, propose solutions, and express their opinions on specific issues or policies (Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN), n.d.). While there are arguments about the effectiveness of town hall meetings, models like the 21st Century Town Meeting have been successful in fostering citizen deliberation and influencing decision-making processes (Lukensmeyer & Brigham, 2002). As Reich argued that deliberation may be time-consuming, but it can be more effective in shaping and maintaining mandates (Reich, 1990 cited in Fischer, 2003); well-designed town hall meetings ensure the legitimacy and acceptance of decisions in policy development by engaging citizens effectively.

In Myanmar, the centralized and tightly controlled policy-making environment lasted under military rule, where citizen participation was limited. The transition from military rule to constitutional government brought some changes, but decision-making processes remained centered around the highest ranks and top-down. The lack of diversity in the civil service (predominantly composed of retired military personnel) and limited research activities contributed to a culture of information hoarding and limited transparency (The Aisa Foundation, 2016). The USDP and NLD governments prioritized enhancing public participation and accountability (Batcheler et al., 2018), but regular engagement with the public, particularly in the municipal sector, was lacking (Batcheler et al., 2018; Roberts, 2018). The study aims to examine the implementation of town hall meetings in a specific local area and identify the supporting and inhibiting factors for promoting town hall meetings nationwide in Myanmar.

Policy Analysis & Findings

(i) Why and how town hall meetings can be implemented?

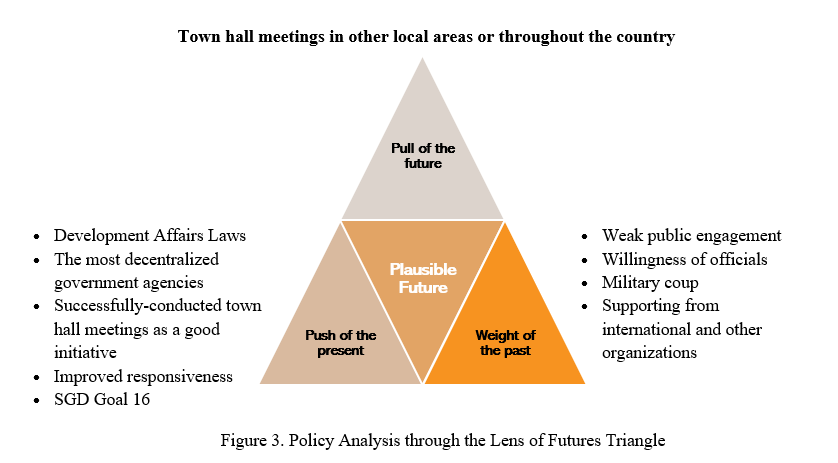

Figure 1. Evolution of Development Affairs Organizations

Figure 1 illustrates changes in legal provisions and the organizational nature of the Development Affairs Organizations (DAOs) over time in addressing the reasons behind why town hall meetings can be implemented in the Sagaing Region. During the colonial period, the British introduced urban governance through the Burma Municipal Act of 1874, which established municipal committees with powers to administer taxation, licensing, and infrastructure development. Subsequent laws extended municipal administration throughout the country. However, the military rule in Myanmar brought changes that limited public participation and representation. Military-backed institutions gained control over municipal governance, weakening citizens’ involvement (Arnold et al., 2015).

In 2011, with political reforms and the establishment of a quasi-civilian government, the Department of Development Affairs was placed under state/regional governments’ control (Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, 2008). The development affairs laws passed by specific state/ regional parliaments were very similar to the 1993 Development Committees Law adopted under the military regime. After taking office by the civilian government in 2015, amendments to the development affairs laws were continued, aiming to enhance transparency, accountability, and public engagement (Myanmar Law Information System, n.d.-a). In Sagaing Region, where town hall meetings were implemented, amendments to the development affairs law granted authority to Township Development Affairs Committees (TDACs) to oversee DAO offices. TDACs, with elected members, played a supportive role in strengthening public relations, ensuring transparency in budgeting and licensing processes, and meeting public needs (Sagaing Region Development Affairs Law, 2018).

While practices during the initial reform period still bore remnants of military rule, subsequent amendments under the civilian government aimed to enhance transparency and accountability. The authority granted to TDACs and the involvement of elected members contributed to addressing public concerns. Thus, evolving nature of development affairs organizations and the legal framework reflects why town hall meetings can be implemented in Sagaing Region.

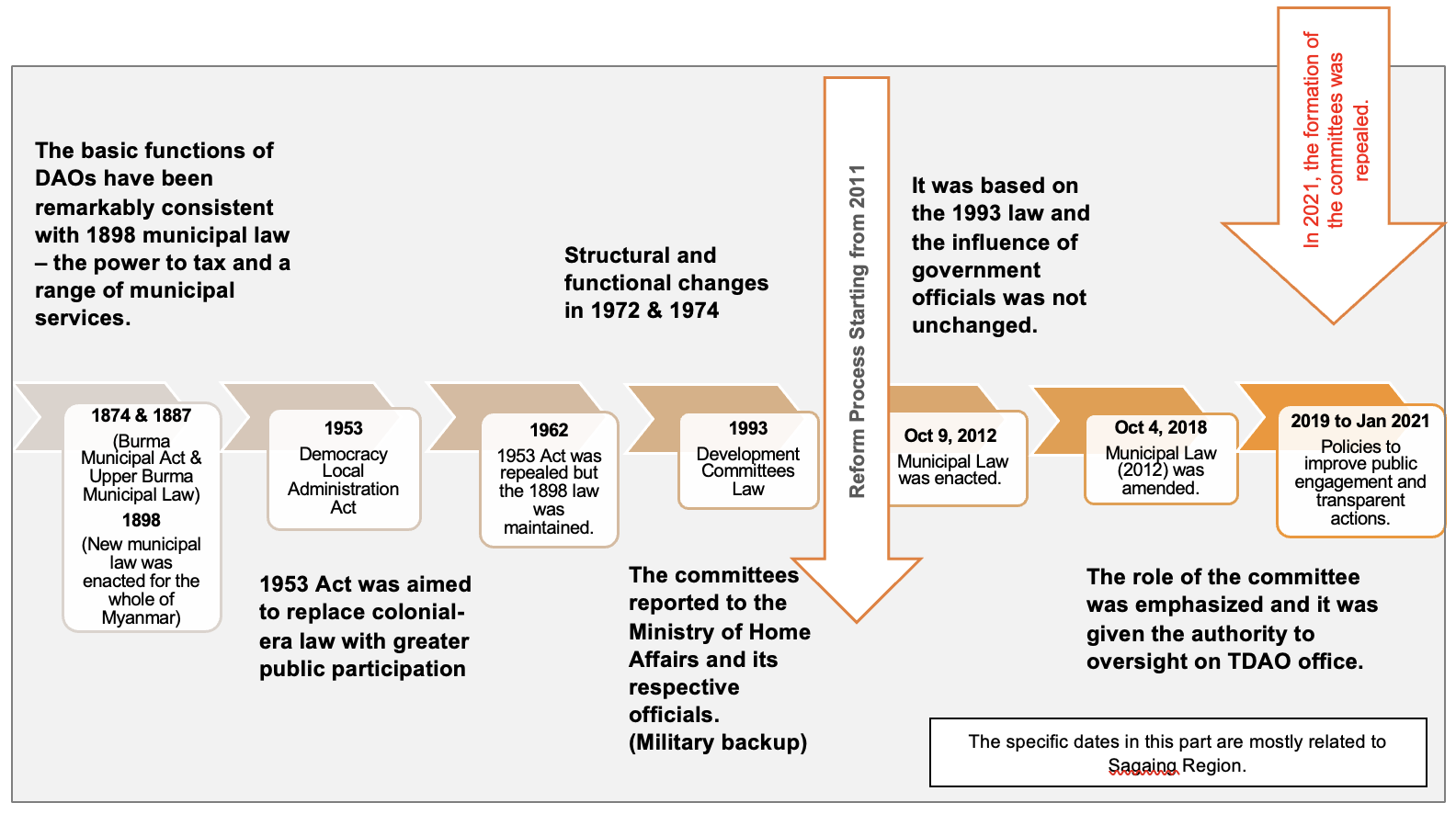

Figure 2. Policy Analysis through the Lens of MSF

Figure 2. explains how town hall meetings can be conducted in Sagaing Region by analyzing the political environment, emerging problems, and policy proposals, utilizing the Kingdom’s multiple streams framework. The political climate around 2017 and 2018, under the newly elected civilian government, was supportive of reforms and emphasized public participation and representation in political institutions (Batcheler et al., 2018).

During this reform process, Development Affairs Organizations (DAOs) faced numerous issues and challenges left unaddressed during the military regime. These problems included improving social services, revenue collection, and enhancing public engagement (Arnold et al., 2015). Civil society organizations and interest groups, assumed as policy entrepreneurs, seized the opportunity to propose policy solutions and address the public engagement problem. Through engagement with the Sagaing Region Parliament and capacity-building initiatives, a civil society organization conducted a project “Citizen Engagement of Sagaing Region Hluttaw.”

This organization could advocate for citizen engagement policy (conducting town hall meetings) to the development affairs organization. The impact of the project with Hluttaw also influenced the development affairs sector, and it rapidly led to the implementation of town hall meetings in respective townships by DAOs. The civil society organization believed that public engagement is crucial for democracy, as it enhances the democratic process, fosters democratic cultures, improves municipal services satisfaction, increases tax revenue, and promotes transparency within DAOs (Pyae Sone Aung, 2019).

Additionally, the cooperation of the DAO executive director of the Sagaing Region and the township-level DAOs played a crucial role in formulating and implementing the policy of conducting town hall meetings. The policy was developed and formulated by Sagaing Region Development Affairs Organization in 2019, leading to the implementation of town hall meetings in two-thirds of the total 37 townships by 2019 and 2020 (Sagaing Region Development Affairs Organization, n.d.). Thus, the importance of the political climate at this period, the engagement of policy entrepreneurs, and the cooperation of DAOs, all those factors explain how town hall meetings can be implemented as part of a broader public engagement policy in the Sagaing Region.

(ii) What are the supporting and inhibiting factors for promoting town hall meetings?

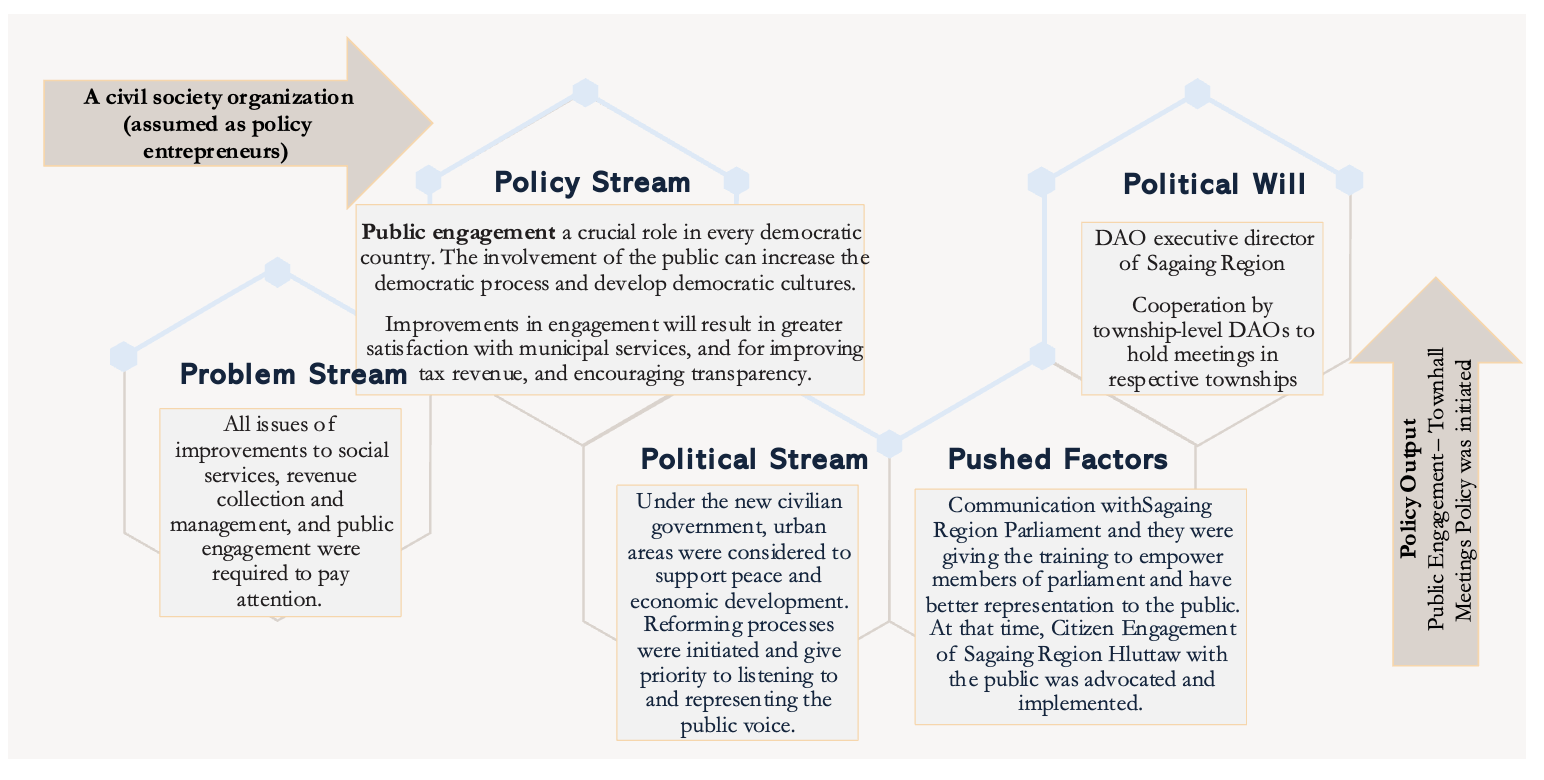

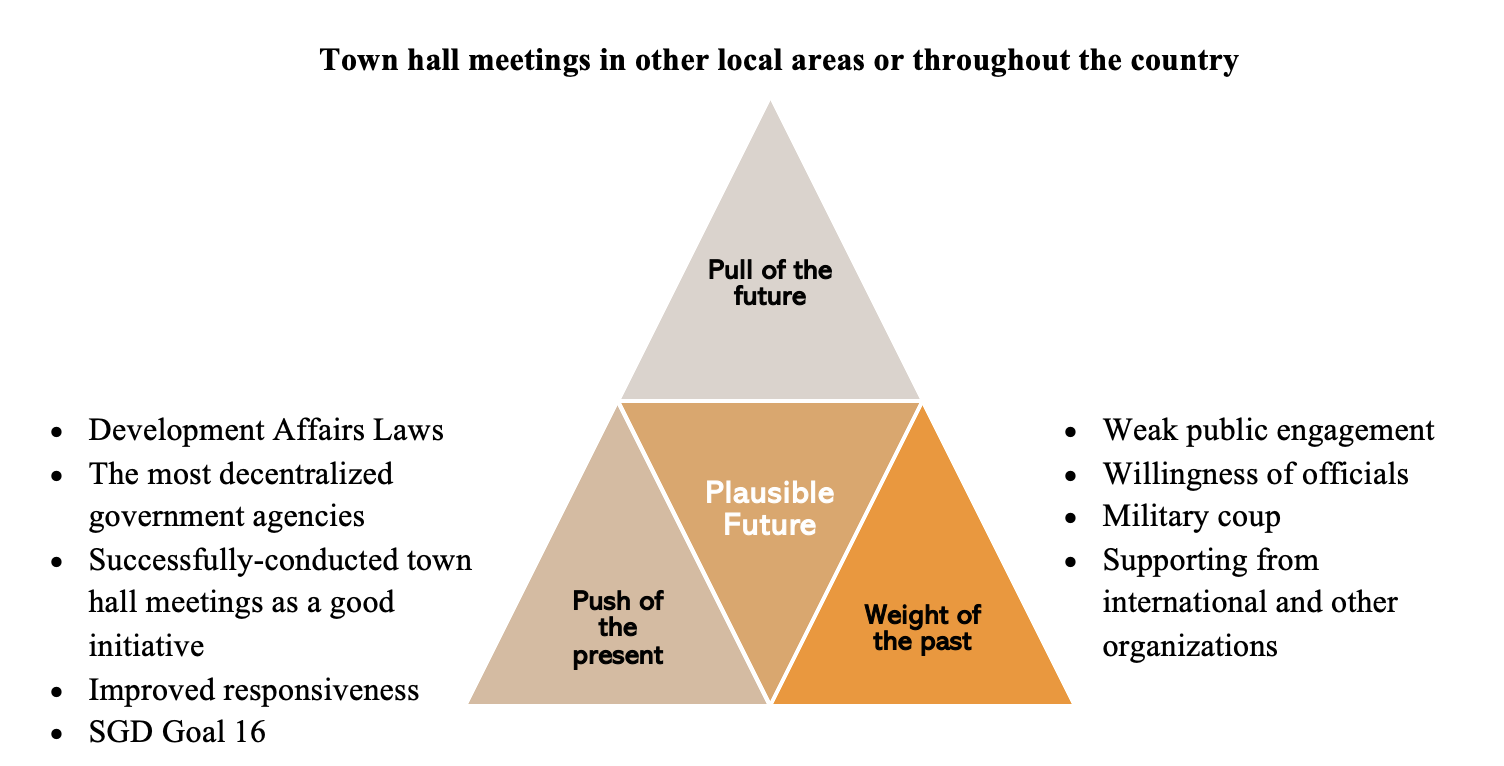

Figure 3. Policy Analysis through the Lens of Futures Triangle

Figure 3 illustrates the supporting and inhibiting factors which are crucial considerations for the future implementation of town hall meetings in other areas or countrywide, based on the findings of the first research question. One supporting factor is the presence of development affairs laws and provisions enacted by each state or region (Myanmar Law Information System, n.d.-a). These laws allow local governments to have autonomy and make decisions that align with their specific needs and priorities. The flexibility to amend policies enables Development Affairs Organizations (DAOs) to address emerging challenges and adapt to changing goals.

Another factor is the political protocol that grants DAOs full control under state or regional governments (Arnold et al., 2015). This autonomy empowers DAOs to find their own solutions and make prompt decisions in implementing new activities, considering local resources, culture, and developmental challenges. The successful implementation of town hall meetings in the Sagaing Region can serve as a model for other regions to adopt similar public engagement policies. This can create a demonstration effect, facilitate knowledge sharing, capacity building, collaboration, and networking, and generate positive public perception. Additionally, improving responsiveness to public needs and utilizing social media for expanded engagement (Roberts, 2018) are further supportive factors for implementing town hall meetings in the future. SDG Goal 16 supports the more comprehensive promotion and adoption of town hall meetings as crucial tools for achieving sustainable and inclusive development (United Nations, n.d.).

However, there are inhibiting factors to consider. The historical legacy of weak public engagement, stemming from the suppression of citizen participation under military rule, poses a challenge. The values and procedures embedded in political institutions hinder the promotion of town hall meetings. The individual willingness of officials in respective township areas also plays a crucial role. Their varying levels of support can impact the success of implementing town hall meetings, depending on different locations.

Moreover, the military coup disrupted the reform process and created political instability. The repeal of obligations for committees mentioned in state/regional development affairs laws (Myanmar Law Information System, n.d.-b) has reduced transparency and accountability. The coup has also led to the discontinuation of projects and the disengagement of international and local NGOs and civil society organizations, further impeding the promotion of town hall meetings.

Thus, the study identifies several supporting factors such as development affairs laws, political autonomy, successful initiatives, and alignment with sustainable development goals. However, inhibiting factors including the historical legacy of weak public engagement, individual willingness, and the impact of the military coup need to be considered in developing strategies for the desired future.

Policy Recommendation

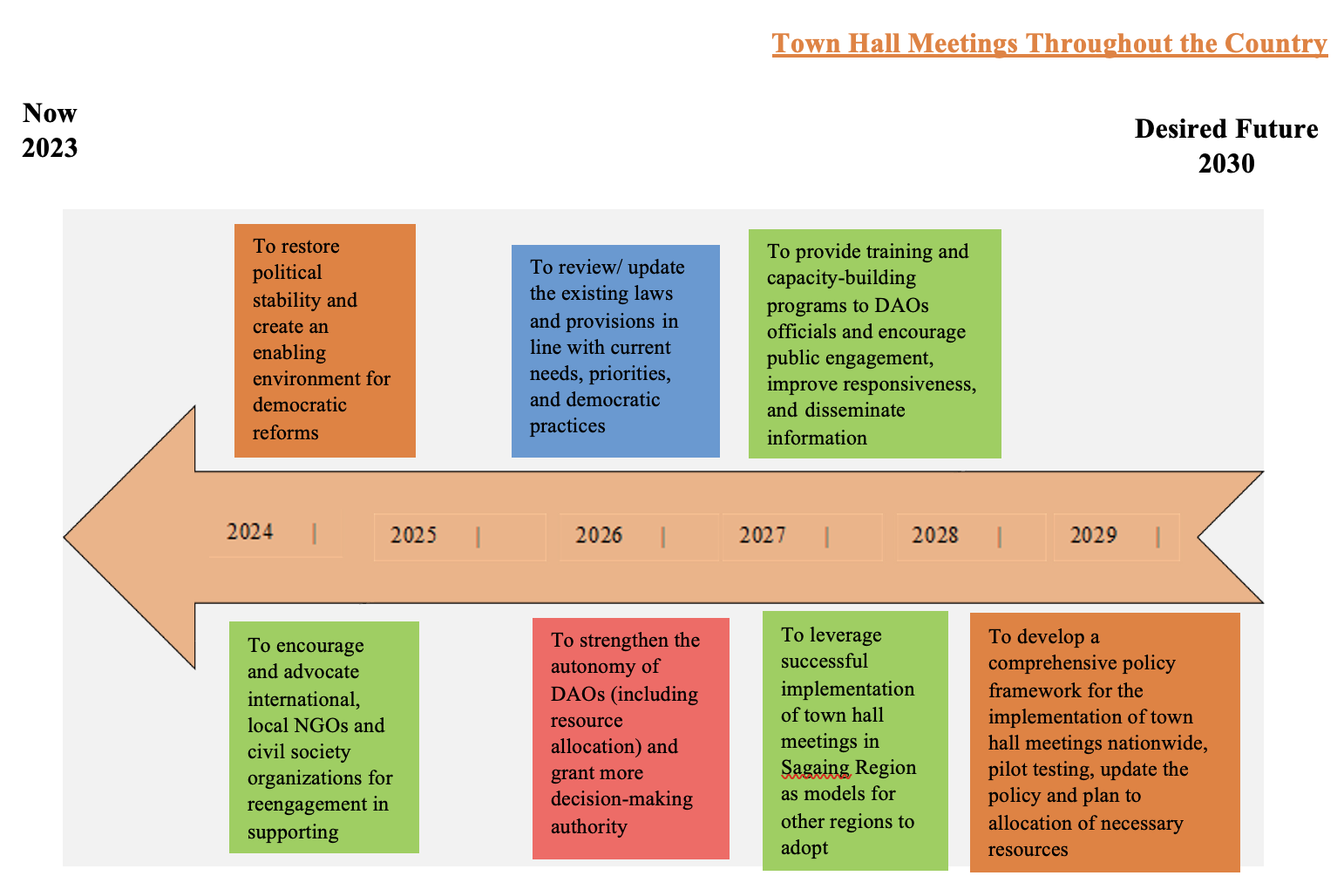

To achieve the desired future of promoting town hall meetings in other areas and implementing them nationwide by 2030, the following strategies and policy recommendations are proposed. Figure 4 shows the brief and the recommendations in detail are followed by the figure.

Figure 4. Backcasting to achieve the desired future

To Restore Political Stability and Enable Democratic Reforms (by 2025):

-

- Focus on restoring political stability and creating an enabling environment aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- Encourage the re-engagement of international and local NGOs and civil society organizations in supporting public participation initiatives and the reform process.

- To Review and Update Development Affairs Laws (during 2026-2027):

- Review and update existing development affairs laws and provisions to align with current needs, priorities, and democratic practices.

- Consider revising provisions that have removed committees comprising elected members, aiming to enhance democratic engagement and participation.

- Strengthen the autonomy of Development Affairs Organizations (DAOs) and grant them more decision-making authority, including improved resource allocation.

- To Leverage Successful Implementations and Knowledge Sharing (during 2027-2028):

- Utilize successful implementations of town hall meetings in the Sagaing Region as models for other regions to adopt.

- Organize regular sharing sessions and workshops to disseminate successful practices and experiences, involving DAOs and other stakeholders.

- Provide specialized training and capacity-building programs, emphasizing the importance of public engagement and participatory governance.

- Encourage public engagement, improve responsiveness, and disseminate information through various communication platforms.

- To Develop Guidelines and Manuals, Pilot Testing, and Planning to Allocate Resources (during 2028-2029):

- Convene a multi-stakeholder working group to develop a comprehensive policy framework for town hall meetings nationwide.

- Select pilot sites and establish clear implementation plans, including guidelines, resources, and support mechanisms.

- Regularly evaluate and monitor pilot initiatives to identify successes, challenges, and areas for improvement.

By following these strategies and implementing the recommended policies, the goal of promoting town hall meetings throughout the country can be realized by 2030.

References

- Arnold, M., Ye Thu Aung, Kempel, S., & Kyi Pyar Chit Saw. (2015). Municipal Governance in Myanmar: An Overview of Development Affairs Organizations (Discussion Paper No. 7; Subnational Governance in Myanmar). The Asia Foundation. https://www.burmalibrary.org/docs21/AF-Municipal_Governance_in_Myanmar-en-red.pdf

- Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN). (n.d.). What to Expect at a Town Hall. Retrieved 23 May 2023, from https://autisticadvocacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/What-to-Expect-at-a-Town-Hall.pdf

- Batcheler, R., Kyi Pyar Chit Saw, Arnold, M., Valley, Ii., Atwood, K., & Thet Linn Wai. (2018). State and Region Governments in Myanmar. The Asia Foundation.

- Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, (2008) (testimony of Republic of the Union of Myanmar). https://www.myanmar-law-library.org/IMG/pdf/constitution_de_2008.pdf

- Fischer, F. (2003). Citizens and Experts: Democratizing Policy Deliberation. In Reframing public policy: Discursive politics and deliberative practices. Oxford University Press.

- Lukensmeyer, C. J., & Brigham, S. (2002). Taking Democracy to Scale: Creating a Town Hall Meeting for the Twenty-First Century. National Civic Review, 91(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncr.91406

- Myanmar Law Information System. (n.d.-a). Region or State<br> Laws [Database]. Region or State <br> Laws. Retrieved 31 October 2022, from https://mlis.gov.mm/lsSc.do?menuInfo=4_1_1

- Myanmar Law Information System. (n.d.-b). Union Laws [Database]. Union Laws. Retrieved 30 October 2022, from https://www.mlis.gov.mm/lsSc.do?menuInfo=2_1_1

- Pyae Sone Aung. (2019). Monywa Townhall Meeting Report. Yone Kyi Yar Knowledge Propagation Society.

- Roberts, J. (2018). Urban Safety and Security in Myanmar (Urban-Safety-Brief-Series-No-1). The Asia Foundation.

- Sagaing Region Development Affairs Organization. (n.d.). Retrieved 29 October 2022, from http://www.srdao.org.mm/

- Sagaing Region Development Affairs Law, no. 6, Sagaing Region Parliament (2018).

- The Aisa Foundation. (2016). Strengthening Government Policymaking in Myanmar [Brief]. The Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/publication/strengthening-government-policymaking-myanmar/

- United Nations. (n.d.). Goal 16 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs [Official website]. United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 26 May 2023, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal16