Evaluating Policy Responses to Social and Economic Consequences of Declining Fertility in Thailand: A Quantitative Approach

Author: Alphonse Badolo

Advisor: Thida Chaiyapa

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

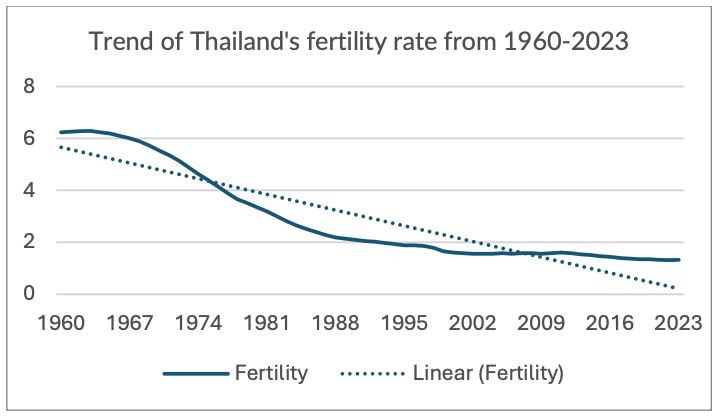

The fertility rate in Thailand has fallen drastically from 6.3 children per woman in the 1960s to 1.3 children per woman in 2022, which is far below the replacement level of 2.1 needed to sustain the population. This demographic shift poses urgent threats to the economic development, stability, and prosperity of the country. This brief evaluates the efficiency of Thailand’s current family policy responses in boosting its workforce using a quantitative approach. The empirical evidence shows that the existing pronatalist policies have failed to reverse or significantly influence fertility trends.

INTRODUCTION

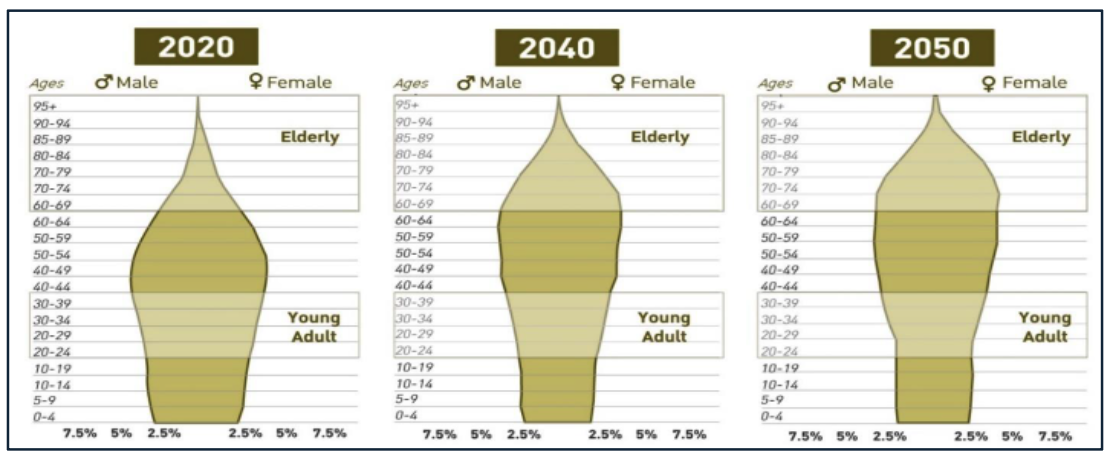

It is well understood that raising children to their full potential is substantially important for social and economic development. This is more so for Thailand as the country is facing several challenges, such as a large informal sector, an ageing population, and a “middle income trap”, that are closely related to the current deficit in human capital formation and development. The current low birth rate, which is resulting in a shrinking population, along with the rapidly ageing population, poses a serious threat to the economic development and prosperity of the country and can be effectively addressed with a more productive workforce. Figure 1 below depicts this phenomenon quite plainly. Such a productive workforce is crucial for sustainable growth, economic competitiveness, and a transition from a middle-income status to a high-income status.

Figure 1: Population distribution by age group, in 2020, 2040, and 2050

Source: World Population Prospects 2015, United Nations.

Overview of Thailand’s fertility trend

Over the past decades, Thailand’s birth rate has been declining sharply, with the total fertility rate falling from 6.14 children per woman in 1960 to the current rate of 1.3 children per woman (Srithanaviboonchai et al., 2014). This phenomenon is significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1, which is required to maintain a stable population. The number of births in 2022 was historically recorded as the lowest in 70 years, with fewer than half a million babies born.

The persistent decline in the fertility rate has been associated with the country’s family planning policy enacted in the 1970s, including the prevalence and promotion of contraceptives, as well as the economic development and urbanisation (Sasiwonsaroj et al., 2020), where smaller families became more feasible as people moved to cities. Others have linked social changes, the rising cost of living, delayed family formation, and celibacy to the issue.

Figure 2:Trend of Thailand’s Fertility Rate from 1960-2023

Source: Author’s compilation based on World Bank Data (2025).

-

Policy motivation, objectives, and gaps in current fertility interventions

There is an urgent need for effective fertility policies to prevent Thailand from labour shortages and an ageing population burden. Effective fertility policies ensure the country stabilises its declining birth rate while limiting the impacts of labour shortages and ageing population burdens. The study focused on assessing the policy responses to the declining fertility rate in Thailand, aiming to identify the root causes of the low fertility rate and the impact of low fertility on the economy. The study employed quantitative techniques like the AutoRegressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model, Interrupted Time Series Analysis (ITSA) model, descriptive statistics, and a Granger causality test for impact analysis.

Child Allowance under the Social Security Scheme (SSS)

The child allowance policy under the SSS was introduced as part of the Thai government’s pronatalist policy efforts to encourage Thai citizens to give birth by providing financial support to families with children. This policy only targets workers in the formal sector who are enrolled in the SSS. It provides a monthly child allowance for children aged 0-6 years, up to three children per family, and it is managed by the Social Security Office (SSO) under the Ministry of Labour (United Nations, ESCAP, 2022). Despite the policy’s increasing budget allocation in the past, this study shows that the policy has been ineffective in improving fertility outcomes. Further, there is a problem of high exclusion error affecting many informal workers and poor families, which undermines the impact of this policy.

Child Support Grant (CSG) for Poor Families

In 2015, the government of Thailand introduced the first-ever non-contributory child benefit (UNICEF, 2019). Since its inception, CSG has undergone expansions both in coverage and the value of the transfer. Nonetheless, CSG excludes a large number of eligible children. An evaluation of this scheme by this study revealed that CSG suffers from an estimated 52% exclusion error. Further, the disbursement amount, currently at THB 600 per child, has still stayed the same for several years, while limiting the effectiveness of this policy. A review of this policy between 2015 and 2024 using the Interrupted Time Series Analysis reveals a relatively constant trend, pointing to the limited impact of this intervention on poverty reduction and enhancement of fertility.

Challenge I: A substantial number of children are missing out on the policy

In Thailand, child benefits can be generally categorised as contributory and non-contributory. However, the two schemes do not function on the same scale to provide full coverage of all children in the age group, such that, as the SSS child allowance targets children whose parents are members of the Social Security System, the CSG, on the other hand, targets only children from poor families. Hence, as many as 631,714 young children as of April 2022 are left out (TDRI, 2024).

Challenge II: The value of the grant support is inadequate

Another policy gap related to the child benefits programme is that the value of transfer is insufficient. Both the contributory SSS child allowance and the non-contributory CSG are too low to raise a young child to their full potential. According to a study by Thailand Development Research Institute (2019), the current values of the two schemes, THB 800 per child per month (SSS child allowance scheme), and THB 600 per child per month (Child Support Grant) are about one-fifth to one-fourth of poverty line and much less than the amount needed to raise a child to a minimum required amount of THB 3,373 per month. Moreso, while the cost of living has increased severalfold because of inflation, the current amount of the CSG has remained the same since 2016.

Challenge III: Pregnant women are entirely missed out

The third challenge associated with the current CSG is that the scheme does not offer any benefits to pregnant women. A key component of a comprehensive social protection system is championing maternity protection. Thus, extending the grant support to include pregnant women are important means of improving income security and access to maternal and child health care. Even countries that have lower per capita GDP than Thailand provide cash benefits to pregnant women. These include India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and Bangladesh.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Despite growing literature, there is no conclusive evidence or determination of a single variable that influences the fertility rate. Many have blamed this phenomenon on government policies like the family planning policy, delayed marriage, changing social norms, economic pressures and uncertainty, and celibacy. Even though a low fertility rate is a multifaceted issue driven by a combination of factors. Nonetheless, the study finds that Thailand’s declining birth rate is primarily driven by urbanisation, economic uncertainty, and labour market dynamics. Contrary to expectations, female education does not significantly impact the birth rate, suggesting that economic considerations outweigh social and political factors in family planning decisions. Besides, the impact analysis revealed that Thailand’s declining birth rate poses long-term economic and social challenges, necessitating strategic policy interventions to stabilise population growth and maintain economic stability.

Based on these conclusions, the following policy recommendations are important for addressing Thailand’s fertility rate and its broader socioeconomic implications.

- The Thai government and policymakers must consider improving the CSG and SSS child allowance schemes. Whereas the current subsidies and child allowance have shown limited impact, improving their design and implementation can enhance effectiveness. This includes adjusting benefits amounts to reflect the real cost of child nurturing, ensuring consistent payments, and widening the policy to include pregnant women and vulnerable working families outside the formal sector.

- There is a need to address the emerging cost of living and household debt: As the finding shows that inflation and household debt have a negative impact on the fertility rate, there is a need for policies such as subsidised housing for young families, regulated childcare costs, and debt management support. These interventions can alleviate financial burdens while having a positive outcome on reproductive decision-making.

- There is a need for mapping out long-term demographic and labour market adjustments. Considering the ageing population, the Thai government should invest in active ageing and automation programmes tailored to improving productivity. Besides, if possible, the government should consider well-managed migration policies to sustain economic growth and support the dependency ratio.

- The government should ensure the mitigation of economic uncertainty and the unemployment rate. Based on the conclusion that economic uncertainty and male unemployment influence short-term fertility decisions, the government should make efforts to create jobs for the youth. This could be supported with unemployment insurance and labour market upskilling programmes to enhance reproductive confidence.

- The government should consider promoting a flexible work environment for female workers. Since female labour participation greatly impacts fertility negatively in both the short and long-term, policies should focus on promoting a friendly working environment through flexible schedules, job protection during maternity or paternity leave, and employer incentives to support working parents.

References

[1] Sasiwonsaroj, K., Husa, K., & Wohlschlägl, H. (2020). Fertility Decline and the Role of Culture – Thailand’s Demographic Challenges for the 21stCentury. In S. Kurfürst & S. Wehner (Eds), Southeast Asian Transformations (pp. 125–152). transcript Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839451717-009

[2] Srithanaviboonchai, K., Rn, W. M., Panpanich, R., MEd, J. S., Chariyalertsak, S., Sangthong, R., Kessomboon, P., Bns, P. P., Nontarak, J., Taneepanichskul, S., & Aekplakorn, W. (2014). Characteristics and Determinants of Thailand’s Declining Birth Rate in Women Age 35 to 59 Years Old: Data from the Fourth National Health Examination Survey. 97(2).

[3] TDRI. (2024). Thailand’s Child Support Grant: An Assessment of the Targeting Method. UNICEF. https://share.google/JlCxn0yxfT4zC3CgZ

[4] UNICEF. (2019). Thailand’s child support grant helps vulnerable families: Leave no children behind. https://www.unicef.org/thailand/stories/thailands-child-support-grant-helps-vulnerable-families

[5] United Nations, ESCAP. (2022). How to Design Child Benefits (ST/ESCAP/3073). https://repository.unescap.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12870/5199/ESCAP-2022-PB-how-to-design-child-benefits.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y

Download full article: Click