Special Needs of Women Workers in The Garment Sector of Myanmar: Analyzing Labor Policies Through Critical Realist Lens

Author: Cho Cho Hlaing

Advisor: Asst. Prof. Pobsook Chamchong, PhD

Introduction

The garment sector, a gendered economy, which experienced rapid growth after the state-led economic reform, is often seen as an opportunity for women to earn an economic position by shifting from subsistence to wage labor. However, the garment sector, a labor-intensive industry that exploits cheap labor in the country, is notorious for exploitative working conditions. Despite some state-led labor policy measures, working conditions never improve. In the post-coup situation, political oppression worsened the garment sector’s working conditions. The existing literature explored the notorious working conditions in the garment sector, unpaid care work covered mainly by women, and the special needs of women workers under different oppressive systems are not given enough attention. In addition, although some policies are in place, women workers’ rights and needs are not adequately protected and addressed. This study identifies the special needs of women workers by employing intersectional feminism and social reproduction feminism and then conducts a critical policy analysis of labor policies in addressing these needs.

Special Needs of Women Workers

This study examines sexual harassment, denied maternity leave and social benefits, unpaid care work, struggle as a migrant worker, patriarchal union practices, and rights violations in post-coup situations as the struggles of women workers in the garment sector of Myanmar.

It can be seen that sexual harassment or verbal abuse is committed by male coworkers and supervisors; most of them are female.[1] Not only one’s gender but also unequal power relationships impact the individual experiences and special needs. In addition to menstrual leave that women workers need (STUM, 2021), their right to maternity leave and miscarriage benefits are also denied. A woman worker who ended up with a miscarriage remembered,

“I don’t bleed much at home. At the factory; however, physical activities that involve moving the lower body parts exacerbate bleeding”.[2]

Patriarchal union practices also hinder women’s participation in leadership positions. Women’s unique experiences are also burdened by domestic labor carried out by women, which is naturalized as a performed duty for the sake of love and care.[3] According to research conducted by ILO, most of the factories don’t have childcare facilities. In the garment sector, the majority of the women workers are internal migrants ( Kusakabe & Melo, 2019), and living expenses in the city impact them differently due to the factory’s lack of transportation and accommodation arrangements (Myint & Lertchavalitsakul, 2021) and indecent wages.

In post-coup situation, women workers are more likely to be encountered with sexual harassment and rape committed by soldiers.[4] By employing feminist theories, this study identifies the special needs of women workers, which are shaped by different oppressive systems, wherein not only gender but also power relations, age, marital status, region, and class determine their experiences.

How do labor policies address these needs, and what are the barriers?

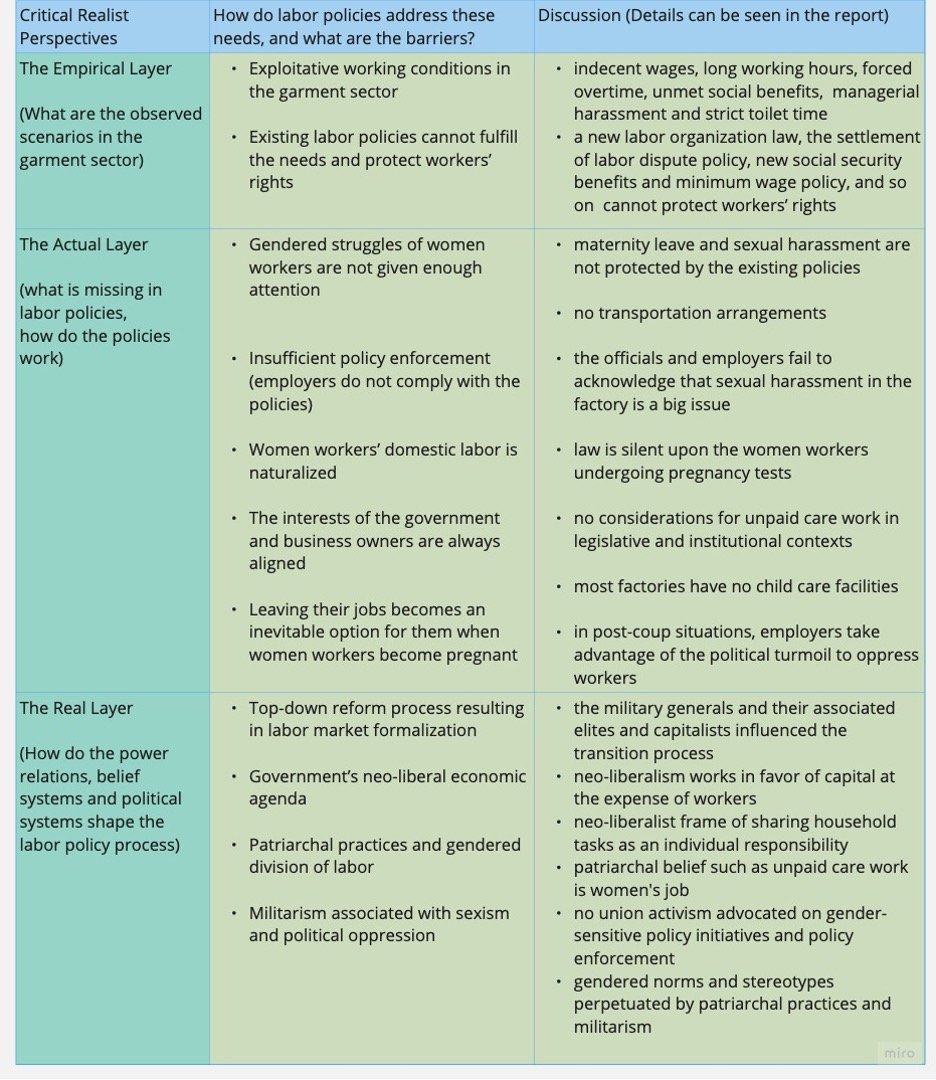

Empirical Layer – what can be observed?

The garment sector in Myanmar is notorious for exploitative working conditions such as indecent wages, long working hours, forced overtime, unmet social benefits such as sick leave, holidays, health care provision, and so on, managerial harassment, and strict toilet time (Progressive Voice, 2016). Regarding the policies, labor market formalization was carried out when the semi-civilian government was backed by the military in 2011. These legislative reforms include repealing outdated labor laws and enacting a new labor organization law, the settlement of labor dispute law, new social security benefits and minimum wage law, and so on (Jinyoung Park, 2014). Learning about the strikes that broke out in the factories concerning indecent wages and factory mismanagement, such as the dismissal of labor unionists, the existing labor policies cannot protect workers’ rights.

Actual Layer- What are the unnoticed events?

The insignificant events to which policies need to give more attention are the gendered struggles of women workers. Lack of transportation arrangements can worsen the sexual harassment experiences of women workers, which can also be found on their way back home. However, the officials and employers fail to acknowledge that sexual harassment is a big issue (Fair Wear Foundation, 2017), resulting in a lack of legislation. Moreover, the law is also silent to address the case of women workers undergoing pregnancy tests before and while they work in the factories. Since women workers’ right to maternity leave is denied, leaving their jobs becomes an inevitable option for them when they become pregnant.[5] As the Social Security Law 2012 suggested, workers are entitled to maternity benefits, including leave and expenses, miscarriage benefits, paternity benefits, and so on (ESCAP, 2021).

What is more invisible is unpaid domestic care work that is covered chiefly by women. According to the 1951 factories act, amended in 2016, factories with over 100 women workers with under-five children must provide daycare facilities with the help of the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief, and Resettlement (Kusakabe & Melo, 2019). Instead of addressing the need for maternity leave and childcare services, the factories recruit younger women who are not married (Fair Wear Foundation, 2017). There are no considerations for unpaid care work in legislative and institutional contexts at the national level (ESCAP, 2021).

The settlement of dispute law that was enacted in 2012 in pursuit of protecting workers’ rights doesn’t work effectively. This is because employers barely follow the decisions of resolution bodies, and they are more accessible to legal support than the workers (Ediger, Laura, and Chris Fletcher, 2017). Although the labor relation before the coup is considered tri-partite conceptually, the interests of the state and the business are always aligned (Fincher et.al, 2021). In post-coup situation, employers are more likely to exploit workers amidst political oppression.

A co-president of the Federations of General Workers Myanmar (FGWM) claimed that;

“In post-coup situation, employers take advantage of current political turmoil and lack of rule of law. Employers failed to conduct negotiations when strikes broke out. Instead, they called the police to intimidate the workers”.[6]

The oppression of workers by employers with the support of military-backed thugs was also common in pre-coup Myanmar.[7]

Real layer -What are the structural problems?

The transition from an authoritarian regime to a quasi-civilian regime in 2010 resulted in labor market formalization. The labor regime in Myanmar is shaped by multiple forces which involve authoritarianism, democratization, and economic liberalization resulting in an upsurge of garment factories and labor activism (Arnold& Campbell, 2017). Myanmar’s transition can be considered a top-down reform process wherein the military generals and their associated elites and capitalists influenced the transition process (Arnold & Campbell, 2017; Jones, 2014, p. 201). Therefore, the transition process resulting in a hegemonic labor market formalization (Campbell, 2019) can be seen as a process led by the semi-civilian government backed by the military to maintain power. Another problem is the neoliberal economic agenda of the government. The neo-liberal government works in favor of local and international capital at the expense of workers whilst strengthening their authoritarian power (Dae Oup Chang, 2022). Labor market formalization in Myanmar can be seen as part of the state-led reform process to attract foreign direct investment and protect capital accumulation.[8] Thus, workers’ rights were not considered important in the neo-liberal economic agenda of the ruling semi-civilian government (Harkins, 2021).

In addition, gendered norms shape better working conditions and gender-sensitive policy enforcement in Myanmar. The military rule in the country for many decades is associated with authoritarianism, patriarchy, and sexual violence (Jessica Nixon, 2021). Patriarchal union practices can hinder the union activism advocated on gender-sensitive policy initiatives and policy enforcement (Evans, 2017). Feminists who are critical of neoliberalism pointed out its profit-maximization principles of cutting social spending, cost-effectiveness, and promoting individual responsibility like sharing household tasks (Kobova’,2016). In post-coup situation, labor rights violations are exacerbated under the disrupted rule of law wherein women workers are more impacted due to patriarchal beliefs perpetuated by militarism.

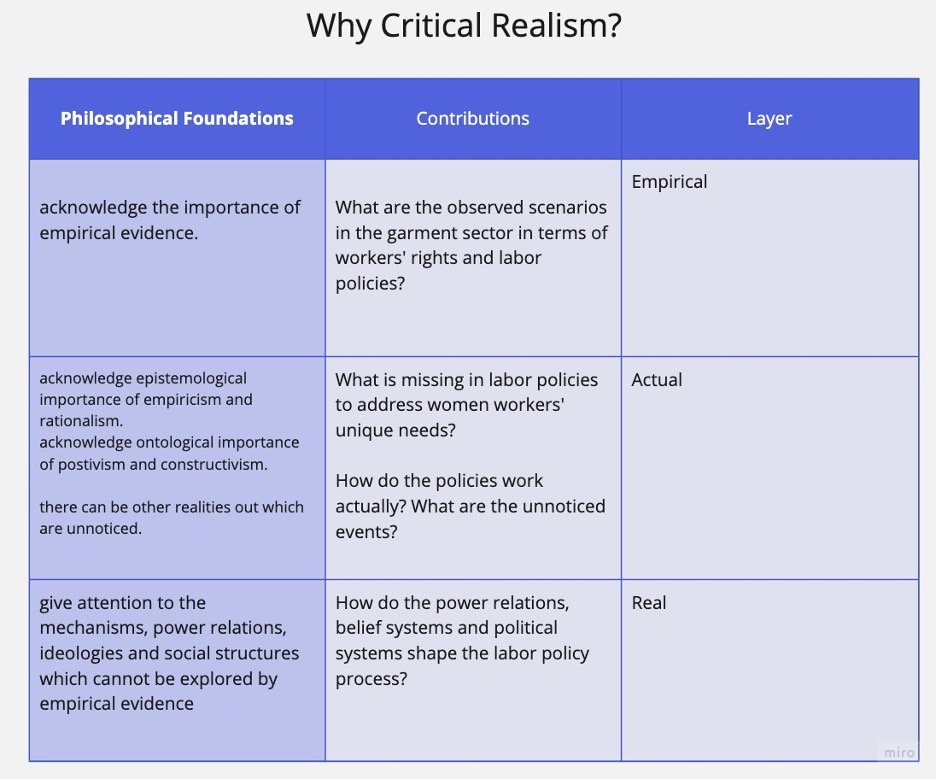

Figure 1 Labor Policy Analysis

Policy Recommendations

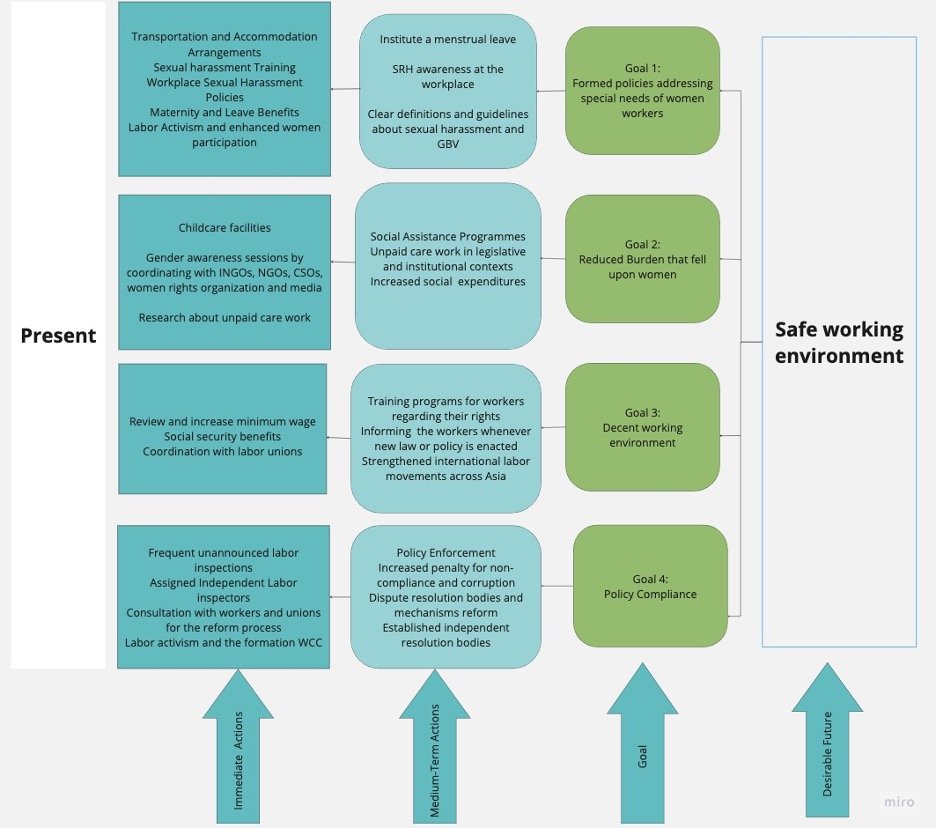

Back-casting works backward by looking forward to the desirable and sustainable future as end-point and policy measures were considered to reach this endpoint (Dreborg, 1996). By employing a back-casting tool, the desirable future of a “safe working environment for women workers where their special needs are met” is seen as an end-point. And then, to achieve this end, policy actions to be undertaken in short and medium terms are recommended.

1. To adopt policies to address the special needs of women workers

Medium-Term Actions

- To institute a menstrual leave officially by amending the Leaves and Holidays Act[9]

- To promote sexual and reproductive health (SRH) awareness at the workplace

- To include clear definitions and guidelines about sexual harassment and gender-based violence in the labor law

Immediate Actions

- To arrange transportation and accommodation for the workers and for those who have to do overtime

- To provide training to workers in terms of sexual harassment

- To adopt workplace policies to prevent the sexual harassment

- To ensure that workers meet their rights to maternity leave, paternity leave, maternity benefits, miscarriage benefits

- To allow the labor activism of women workers by increasing women’s participation in leadership positions of Trade Unions and Labor Unions (to the trade unions and labor unions)

2. To ensure that burden that fell upon women due to stereotypes and gendered division of labor is reduced.

Medium-Term Actions

- To create social assistance program (for instance, the Maternal and Child Cash Transfer Program (MCCT) given to pregnant women [10]). Focusing on unpaid care work is more than sharing household tasks. Creating social assistance programs can decrease women’s economic hardship and facilitate their participation in the labor force (ESCAP, 2021).

- To focus unpaid care work as one of the main components in legislative and institutional contexts, e.g. National Strategic Plan

- To increase social expenditures

Immediate Actions

- To provide childcare facilities by the factories with the assistance of the Social Welfare Department according to the 1951 factories act

- To promote gender awareness programs by coordinating with INGOs, NGOs, CSOs, women’s rights organizations, and media groups to break gendered norms and stereotypes

- To conduct research to explore the missing link of unpaid care work in gender studies

3. To establish a decent working environment that respects the workers’ rights

Medium-Term Actions

- To conduct training programs for workers regarding their rights (especially for labor unions and trade unions)

- To inform the workers whenever new law or policy is enacted by working together with labor unions and trade unions

- To strengthen the international labor movements across Asia (to labor unions and trade unions) so that workers’ experiences and how the labor policies work across the region can be shared. By establishing international solidarity, workers’ rights can be demanded in a collective manner.

Immediate Actions

- To review the minimum wage that needed to be renewed since 2020

(Increased inflation rates and prices of commodities determine the remittance of women workers, which determines their economic position and power hierarchy in a household. Migrant women workers are more impacted due to the expenses of living in a city)

- To ensure that women workers meet social security benefits

4. To ensure that the factories comply with the national labor standards

Medium-Term Actions

- To ensure policy enforcement according to the settlement of dispute policy

- To amend the settlement of dispute policy by increasing the penalty for non-compliance and corruption. The current “500,000 MMK” fine is insufficient for employers to comply with the rules or the decisions.[11]

- To reform the dispute resolution bodies and mechanisms

- To establish the independent and transparent dispute resolution mechanism

Immediate Actions:

- To conduct the frequent labor inspection unannounced to ensure that workers meet the social security benefits

- To assign the independent labor inspectors

- To consult with workers and unions for the policy reform process

- To allow labor activism and the formation of a workplace coordination committee (WCC) according to the settlement of dispute policy (According to the settlement of dispute policy, WCC should be formed with two representatives from workers and employers)

Figure 2 Policy Recommendations

References:

- Addressing Unpaid Care Work in ASEAN. (2021). ESCAP, ASEAN. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/

- Arnold, D., & Campbell, S. (2017). Labour Regime Transformation in Myanmar: Constitutive Processes of Contestation: Labour Regime Transformation in Myanmar. Development and Change, 48(4), 801–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12315

- Arslan, A. (2022). Relations of production and social reproduction, the state and the everyday: Women’s labour in Turkey. Review of International Political Economy, 29(6), 1894–1916. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1864756

- Boonmavichit, T. N., & Boossabong, P. (2022). Approaching Foresight through Critical Realism: Lessons Drawn from Thailand. Journal of Futures Studies. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.202206_26(4).0005

- Campbell, S. (n.d.). Interrogating Myanmar’s ‘Transition’ from a Post-coup Vantage Point. Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia.

- Campbell, S. (2019b). Labour Formalisation as Selective Hegemony in Reform-era Myanmar. The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14442213.2018.1530294

- Campbell, S. (2018). Between labour and the law [Personal communication].

- Chang, D. (2015). From Global Factory to Continent of Labour. 1.

- Chang, D. (2022, October 26). Asian Labour Movements in the Age of Decaying Neoliberalism. Asian Labour Review. https://labourreview.org/challenges-to-the-asian-labour-movements/

- Cheria, M. (2023, March 31). Striking Against All Odds. https://labourreview.org/strike-in-myanmar/

- Dreborg, K. H. (1996). Essence of backcasting. Futures, 28(9), 813–828. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(96)00044-4

- Duran, A., & Jones, S. R. (2020). Intersectionality (pp. 310–320). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004444836_041

- Evans, A. (2017b). Patriarchal unions = weaker unions? Industrial relations in the Asian garment industry. Third World Quarterly, 38(7), 1619–1638. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1294981

- Ferguson, S. (2008). Canadian Contributions to Social Reproduction Feminism, Race and Embodied Labor. Race, Gender & Class, 15(1/2), 42–57.

- Ferrant, G., Pesando, L. M., & Nowacka, K. (2014). Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes.

- Fincher, R., Cornell ILR and Workplace Resolution, & Phoenix. (2021, April). MYANMAR The Future of Labor Relations in Myanmar: After the Coup d’Etat. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/labor_law/publications/ilelc_newsletters/issue-april-2021/labor-relations-in-mayanmar/

- Fraser, Nancy. (2016). Capitalism’s Crisis of Care [Personal communication].

- Gender Forum: One Year Later. (2018). Fair Wear Foundation.

- Harkins, B. (n.d.). Workers’ rights in Myanmar: A decade of fragile progress comes under threat. OpenDemocracy. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/beyond-trafficking-and-slavery/workers-rights-in-myanmar-a-decade-of-fragile-progress-comes-under-threat/

- Harkins, B., Lindgren, D., Ravisopitying, B., Kelley, S., Aye, T. H., & Min, T. H. (n.d.). FROM THE RICE PADDY TO THE INDUSTRIAL PARK: Working conditions and forced labour in Myanmar’s rapidly shifting labour market. Livelihoods and Food Security Fund.

- Henry, N. (2015). Trade union internationalism and political change in Myanmar. Global Change, Peace & Security, 27(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2015.997688

- Holmberg, J., & Robert, K.-H. (2000). Backcasting—A framework for strategic planning. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 7(4), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500009470049

- Huynh, P. (n.d.). Employment and wages in Myanmar’s nascent garment sector.

- Ingen, M. van, Grohmann, S., & Gunnarsson, L. (Eds.). (2020). Critical realism, feminism, and gender: A reader. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jeppesen, S. (2005). Critical Realism as an Approach to Unfolding Empirical Findings: Thoughts on Fieldwork in South Africa on SMEs and Environment.

- Jessop, B. (2004). The Gender Selectivities of the State: A Critical Realist Analysis. Journal of Critical Realism, 3(2), 207–237. https://doi.org/10.1558/jocr.v3i2.207

- Jones, L. (2014). The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Transition. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 44(1), 144–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.764143

- Kusakabe, K., & Melo, C. (2019). JOBS IN SEZs: Migrant garment factory workers in the Mekong region. Asian Institute of Technology and Mekong Migration Network.

- Kyaw, M. N. (n.d.). အထည်ချုပ် စက်ရုံတချို့ ကိုယ်ဝန်ဆောင် အလုပ်သမားများအား အလုပ်ထုတ် နေ. Myanmar Labour News. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://www.myanmarlabournews.com/news/656

- Matthaei, J. (2018, June 19). Feminism and Revolution: Looking Back, Looking Ahead. Great Transition Initiative. https://greattransition.org/publication/feminism-and-revolution?fbclid=IwAR1lgJq8HfksAhR_N2hzN0IMZYc_ViJU0v-S1TlHTQLE8QWmEvQ4-tbFBJ0

- Myanmar Garment Sector FACTSHEET. (2022). EuroCham Myanmar.

- Myint, S. Z., & Lertchavalitsakul, B. (2021). Gender and Remittances: A Case Study of Myanmar Female Migrant Workers at a Garment Factory in Yangon, Myanmar.

- Myo, E. (n.d.). Identifying Major Labour Policy Issues in Myanmar. SAGA Asia Consulting Company Ltd.

- Nandar, W., & Pyae, H. M. (2020, January 13). Garment industry policies endangering pregnancies, women’s health. Myanmar Now.

- Ngwenya-Tshuma, S., & Zar Ni Lin, M. (2022). The impact of the double crisis on the garment sector in Myanmar. https://www.twai.it/articles/impact-double-crisis-garment-sector-myanmar/

- Nixon, J. (2021, June 25). “No to Dictatorship, No to Patriarchy”: Women’s Activism in Myanmar –. https://peaceforasia.org/no-to-dictatorship-no-to-patriarchy-womens-activism-in-myanmar/

- Nyan, S., & Maung, Y. Y. K. (2020, October 15). Advancing the Rights of Women Workers through the 2020 Elections. Tea Circle. https://teacircleoxford.com/policy-briefs-research-reports/advancing-the-rights-of-women-workers-through-the-2020-elections/

- Organising women factory workers in Myanmar to demand their labour rights. (2021). Solidarity of Trade Union Myanmar (STUM) MYANMAR.

- Park, J. (2014). Asian Labour Update:Labour Laws in Myanmar. Asia Monitor Resource Center.

- pdf. (n.d.). Retrieved February 28, 2023, from http://www.mekonglandforum.org/sites/default/files/Political_Economy_of_Land_Governance_in_Myanmar.PDF

- Quinlan, E., Robertson, S., Carr, T., & Gerrard, A. (2020). Workplace Harassment Interventions and Labour Process Theory: A Critical Realist Synthesis of the Literature. Sociological Research Online, 25(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780419846507

- Quist, J., & Vergragt, P. (2006). Past and future of backcasting: The shift to stakeholder participation and a proposal for a methodological framework. Futures, 38(9), 1027–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.02.010

- Raising-the-Bottom-Layout-English-Version-15-11-20161.pdf. (n.d.).

- Sassen, S. (2000). Women’s Burden:Counter Geographies of Globalization and Feminization of Survival.

- Scurra, N., Woods, K., & Hirsch, P. (2015). The Political Economy of Land Governance in Myanmar. The University of Sydney.

- Smith, S. (n.d.). Black feminism and intersectionality. International Socialist Review.

- Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. (2018). Pluto Press.

- Tithi Bhattacharya (Ed.)—Social Reproduction Theory_ Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression-Pluto Press (2017).pdf. (n.d.).

- Wai, M. T. T. (2023, January 31). “Fight on Our Own and Build Solidarity”: A Conversation with Ma Tin Tin Wai of Federation of General Workers in Myanmar [Interview]. https://labourreview.org/fight-on-our-own/

- Weaving Gender Challenges and opportunities for the Myanmar garment industry Findings from a gender-equality assessment in selected factories. (2018). ILO Country office for Myanmar.

- Xue, J. (2022). A critical realist theory of ideology: Promoting planning as a vanguard of societal transformation—Jin Xue, 2022. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14730952211073330

Note:

[1] https://teacircleoxford.com/policy-briefs-research-reports/advancing-the-rights-of-women-workers-through-the-2020-elections/

[2] https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/garment-industry-policies-endangering-pregnancies-womens-health/

[3] https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/nancy-fraser-interview-capitalism-crisis-of-care

[4] https://burmese.dvb.no/archives/585189

[5] https://myanmar-now.org/en/news/garment-industry-policies-endangering-pregnancies-womens-health/

[6] https://labourreview.org/fight-on-our-own/

[7] https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/myanmar-garment-workers-remain-on-strike-10172018171721.html

[9] https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/STUM-FPAR-Briefer.pdf

[10] https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/legacy_rct_brief.pdf/

[11] Ediger, Laura and Chris Fletcher. 2017. “Labor Disputes in Myanmar: From the Workplace to the Arbitration Council.” Report. BSR, San Francisco.