The quest for a policy preserving press freedom and journalist safety

Author: Ye Wint Hlaing

Advisor: Asst. Prof. Pobsook Chamchong, PhD

-

Problem statement

Myanmar media reform was conducted 2012 changing media policy from state regulation system to self-regulation system by abolishing the 60 years old censorship board and establishing Interim Press Council.

Under the self-regulation system, the Interim Myanmar Press Council introduced a Code of Conduct for Myanmar journalists in May 2014. Subsequently, in late 2014, the quasi-civilian government enacted the News Media Law, bringing significant changes to the media landscape in Myanmar. In contrast, the News Media Law guarantees press freedom and indicates the Press Council as the body responsible for resolving conflicts between media and citizens and preventing legal action against journalists or media organizations (UNESCO, 2016 ).

Even in the same year 2014, eight journalists were prosecuted under criminal laws. This is the obvious failure of quasi-civilian government that they did not compliance with the self regulation system they crafted.

In May 2016, Dr. Pe Myint was asked about the future of Myanmar’s media law in another interview conducted by Frontier Myanmar, and he admitted that a handful points in the law need adjustment. He will collaborate with media associates and find out which points should be amended. (PeMyint, 2016).

After next four years, (Athan, 2020), 69 journalists were prosecuted under criminal laws during the tenure of the NLD government. It demonstrates that the government and military filed 44 out of 69 (63%) criminal lawsuits against journalists, including the case of two Reuters journalists,(NEWS, 2019 ) . In light of these facts, the question arose as to why the government and military charged journalists with criminal offenses rather than filing complaints with the Myanmar Press Council as mandated by the media policy (2014 news media law). In order to avoid legal action, journalists began to engage in self-censorship and criticize less government and military misconduct. As a result, the quality of the news and media content they produced declined, and they were unable to fulfill their primary responsibility as whistleblowers.

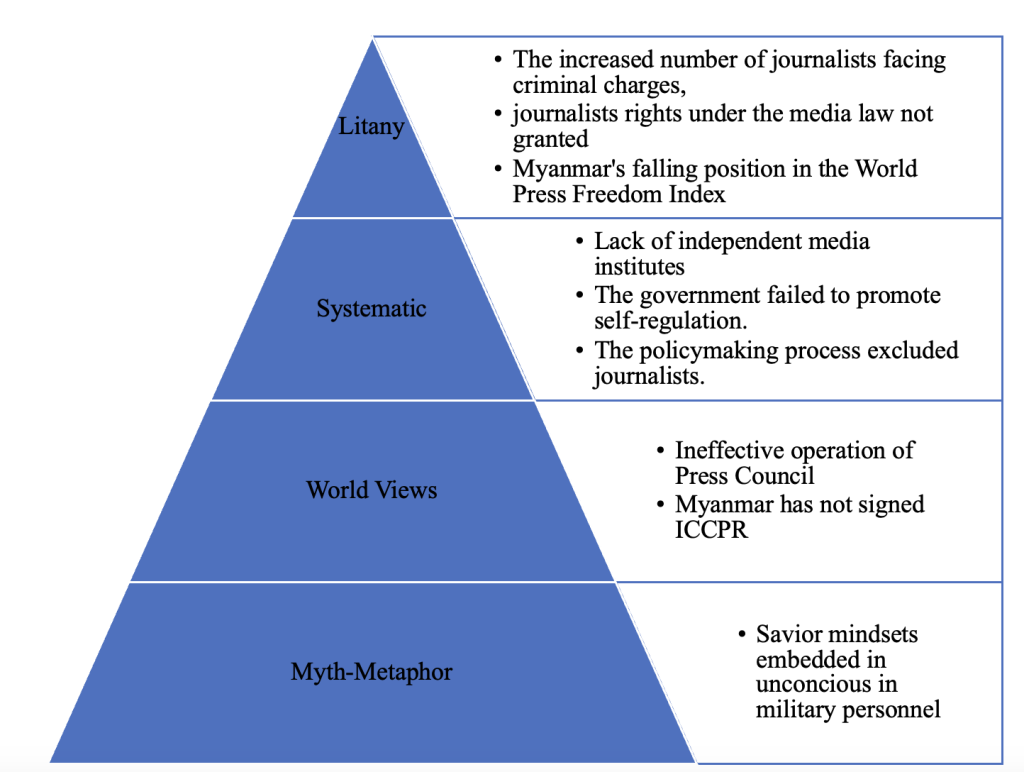

Therefore, the ineffectiveness of a new policy for the Myanmar Media must be examined in order to gather the knowledge necessary for the process of formulating or amending a policy to support promoting press freedom and ensuring the safety of journalists in future reforms. The causes of the new policy for the Myanmar Media Sector’s inefficiency during the country’s democratic transition (2010-2020) were examined using the CLA method.

-

Analysis

Litany:

‘‘Some points in the law need amendment. I must discuss this with associates in the media sector. It would be helpful if the men of the media world met to discuss and decide on what should be amended and how. It will speed up the job. I will assist as best I can’’. (PeMyint, 2016).

The information minister, U Pe Myint was asked about his future on Myanmar’s media law in interview conducted by Frontier Myanmar. However, even at the end of the NLD government’s term, nothing concrete has emerged outside of a few meetings between the ministry of information and the Myanmar Press Council.

But after five years of policy changes, the rise in the number of journalists facing criminal charges, the government’s failure to grant journalists rights under the media law, and Myanmar’s falling position in the World Press Freedom Index, those issues came to light as obvious issues causing the media policy’s ineffectiveness and required immediate attention.

In the last three years of the NLD government’s rule, Myanmar’s ranking on the World Press Freedom Index dropped from 131st in 2017 to 140th in 2020. (RSF, 2020).

Furthermore, the safety of journalists and access to information from government ministries by the media were guaranteed in the news media law enacted in 2014 (in Article 6 and 7) (Law, 2014 ). But since the media law was passed in 2014, these rights have never been provided by the government in power. In practice, the reality differed significantly from what was outlined in the news media law. Journalists who ventured into areas impacted by armed conflicts and reported on them did not receive the protection promised by the security forces. Additionally, when journalists sought essential information from government ministries to enhance their media content, their requests were consistently denied by the government.

Systemtic Causes: System, Structure and Historical Evolution

At the deeper layer of CLA, issues around press freedom and media policy in Myanmar needed to be approached from social or structural points of views including political, economic, cultural and historical. The findings here reveals political, institutional, and historical factors influencing the efficacy of media policy for Myanmar’s media sector.

In 2012, Myanmar introduced a self-regulation system for its media sector, marking a significant and recent change. Under this system, the code of ethics plays a crucial role in determining whether a news story or article produced by the media or journalists is considered ethical.

Prior to 2014, Myanmar lacked a widely accepted code of conduct for journalists, familiarity with international standards, and limited access to independent professional training institutes (UNESCO, 2016 ). The country’s diversity and prolonged civil conflicts further complicated reporting on sensitive issues related to religious minorities, ethnicities, and armed conflicts. Without adequate training and technical support, journalists faced challenges in producing professional and in-depth content. Consequently, some journalists may have violated ethical guidelines in their reporting. This led to a perception among the military and the ruling government that journalists did not adhere to professional standards, or the self-regulation system outlined in the new media policy.

The government did not conduct any public awareness campaigns to educate the general public about the new media policy (self-regulation system) and the important role of the media in a democratic society. As a result, most people in Myanmar were unaware of the changes in the media sector, including the media law and the Myanmar Press Council’s role in self-regulation. Many individuals were not well-informed about the media law, the functions of the Myanmar Press Council, or the process for submitting complaints against the media for insulting or spreading false information. The illiteracy of the public regarding the new media policy could be one of the factors undermining the policy’s effectiveness.

When the military government was planning and drafting the media reform plan, international organizations and experts provided substantial support to the Ministry of Information to develop the most relevant policy for Myanmar media. Additionally, the capacity building training and exposure trips to European countries were only provided to the staff and high ranked officials from the Ministry of Information. During this period, the primary stakeholders, the journalist community, were excluded from the policymaking process, leading to a lack of adequate knowledge and familiarity with the new policy in its initial stages of implementation. As a result, there were instances where journalists, unaware of the policy’s specifics, failed to attend summons by the Press Council regarding unethical news practices. This, in turn, had an impact on the effectiveness and functioning of the Press Council.

World Views: Discourses, Worldviews and Ways of Knowing

Equally essential, in order to strengthen press freedom in Myanmar, we must also address the issue of worldview or discourse scenarios, the third and deepest layer of the CLA.

‘‘Media self-regulation – a system developed voluntarily by media professionals to ensure respect for their professional and ethical guidelines’’ (Hulin, 2014 ). e Press Council’s main role, from a broader perspective, is to safeguard citizens’ rights by serving as an impartial arbiter in resolving disputes between the media and the public (Suriyanto, 2018). By making its activities transparent to the public, the Press Council upholds its position as a fair mediator, earning respect from all parties involved. However, the Myanmar Press Council, as per section 20 of the Myanmar Media Law (By Laws), is mandated to publicize the outcomes of handling complaints and warnings issued to media or journalists who breach the code of ethics. Regrettably, since its inception in 2015, the Myanmar Press Council has failed to fulfill this obligation, resulting in reduced transparency in its operations and impacting its impartial judicial function.

As a consequence, various stakeholders, including the government, the military, and the general public, perceive the Press Council as favoring and protecting the media and journalists. This erosion of public trust has discouraged these parties from seeking resolutions through the Press Council. Consequently, they are exploring alternative ways to address media-related issues, such as filing lawsuits against media and journalists.

International law protects freedom of expression through different treaties and declarations, recognizing it as a fundamental right. The right to freedom of expression is specifically guaranteed in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and also in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) (UNESCO, 2016 ).

Myanmar has agreed to follow the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), but it has not signed or agreed to other international agreements concerning freedom of expression, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) or the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). Even though Myanmar is not a signatory to the ICCPR, some parts of it, like Article 19, are considered customary international law.

Chapter 8 of the 2008 Constitution, Article 354 guarantees: . “ Every citizen shall be at liberty in the exercise of the following rights, if not contrary to the laws, enacted for Union security, prevalence of law and order, community peace and tranquility or public order and morality:

a. to express and publish freely their convictions and opinions;

b. to assemble peacefully without arms and holding procession;

c. to form associations and organizations” (Myanmar, 2008).

The wording ‘‘if not contrary to the laws, enacted for Union security, prevalence of law and order, community peace and tranquility or public order and morality’’ (Myanmar, 2008) which can be interpreted very vaguely and widely particularly for the country like which had been dictated by military regime for almost 60 years. As a result, there is a risk of broad interpretations of the rules, which can pose a threat to freedom of expression. Moreover, the purpose of protecting freedom of expression in a constitution is to establish limitations on regular laws that might otherwise affect it. However, Article 354 allows ordinary laws to bypass the protective measures outlined in the constitution (UNESCO, 2016 ). This creates a problem because Myanmar has numerous laws that can be utilized to restrict freedom of expression. The issue of press freedom in Myanmar and the legal safety of journalists may have resulted from this. This means that amending the current media law alone will not result in increased press freedom and journalist safety unless article 354 in the 2008 situation was changed as well.

U Zaw Myint Maung, a prominent NLD senior executive committee member and Mandalay city chief minister, stated that ”our country, Myanmar, has only three pillars: executives, legislatives, and the judiciary. There is no fourth pillar according to the our constitution” during the Mandalay region’s regional fourth meeting, a joint meeting of representatives from the regional government, judiciary, and legislative branches, as well as Mandalay-based media representatives, including members of the Myanmar Press Council. But on the other hand, in the 2014 news media law mentioned clearly that media is regarded as a fourth pillar of the country. It indicates that the current NLD government, which is widely regarded as a democratic government by both the general public and the international community, denied that the media served as the fourth pillar of democratic nations, which is viewed as a metaphor from a global perspective. Because of this, when there is a dispute between the government and the media, the government frequently decides to bring a lawsuit against the media in order to settle the issue.

Myth and Metaphor: Unconscious Beliefs, Metaphor and Myths

Myanmar has been dictated by the military regime for almost 60 years during that times no independent private media were not able to operate within the country. Throughout the six decades of its occupation, the military has increased efforts to place recently retired military officers in civilian positions in a variety of branches of government, including the Supreme Court, the Energy Ministry, the Health and Education Ministries, and others (Wade, 2015). Additionally, according to the 2008 constitution, 25% of the seats in the parliament are effortlessly allocated to military lawmaker (Myanmar, 2008). Additionally, in Myanmar, the ministries of border affairs, defense, and home affairs are overseen by military-appointed ministers. Myanmar has endured one of the world’s longest civil wars, engaging in conflicts with ethnic armed groups since gaining independence from the British. Consequently, military personnel and government officials within these ministries often view security matters solely through the lens of armed soldiers. They fail to grasp the media’s crucial role as the fourth pillar in ensuring checks and balances within the country.

When the media seeks vital information under the people’s right to know, they are met with denials and excuses, claiming the information is classified for national security reasons. Consequently, when the media publishes critical articles without their input, these officials unconsciously interpret it as a threat to national security. As a result, they respond by prosecuting the media under criminal laws rather than resorting to filing complaints with the Press Council.

The military and former military personnel are deeply ingrained in security-focused mindsets, viewing themselves as saviors or protectors of the nation. This perspective poses extreme risks not only to journalists but also to the entire society in a nation like Myanmar, currently undergoing a democratic transition.

-

Policy Recommendation

In conclusion, for the purpose of responding to the research question, the causes of the new policy for the Myanmar Media’s inefficiency during the country’s democratic transition (2010-2020) were examined using the CLA method. In short, press freedom in Myanmar is threatened by numerous factors, starting with the organizing of public campaigns to the signing of international treaties ensuring freedom of expression. The two layers of most immediate causes—litany and social causes—appeared in the initial phase. However, a more thorough examination of the subject led to the emergence of the world views or discourse layer, the metaphor and myth layer, each with their own cause and being more general and rooted in the problems than the previous layer.

Neither the quasi-civilian government nor the NLD administration made any effort to identify potential remedies to boost the effectiveness of the current media policy for the benefit of media freedom and enhance the operation of the self-regulation system. After six years of implementation, the policy became ineffective as a result of the ruling governments’ failures mentioned in the previous session, taking into account the recommendations and suggestions for the policy amendment made by the media sector, local CSOs and international organizations. Based on the aforementioned findings derived from the use of CLA, it can be ultimately concluded that the media policy implemented by Myanmar in 2014 proved largely unsuccessful. This failure can be attributed to a significant extent to the absence of political determination in promoting press freedom in Myanmar during the period from 2010 to 2020. Both the NLD government and the Myanmar military, which spearheaded Myanmar’s democratization, demonstrated a lack of commitment to this cause.

The following recommendations, developed using the CLA framework, must be put into action right away in order to strengthen the current media self-regulation policy and advance media freedom in Myanmar.

Litany: In the first layer, there are three causes: the rise in the number of journalists facing criminal charges, the government’s failure to grant journalists rights under the media law, and Myanmar’s falling position in the World Press Freedom Index, all of which contribute negatively to the effectiveness of media policy. To address the above-mentioned problems, the government and the military are the main stakeholders who should not consider taking legal action against the media whenever disputes happen between them and the media. When there is a dispute between the government or the military and the media, they should always consider first filing a complaint about the dispute with the complaint mechanism of the Myanmar Press Council in accordance with 2014 media laws. The immediate action which needed to be done by the government and the military is to respect and practice in accordance with the media policy and 2014 news media law. Then the following recommendations should be implemented.

- Through an extensive consultation process with key relevant stakeholders, such as the government, the military, the Press Council, and local CSOs, the media policy should be reviewed and evaluated to determine which provisions of the 2014 media law require revising.

- The government must ensure that journalists are granted the rights afforded to them under the 2014 news media law.

In the second layer, the findings suggest the need for two specific actions.

- Firstly, there is a requirement to raise public awareness about the self-regulation system and the role of the Myanmar Press Council. This can be achieved through the implementation of a public awareness campaign. To accomplish this, the Myanmar Press Council, in collaboration with journalists’ associations and the Ministry of Information, should play a prominent role, supported by international donor organizations. Online and social media should be considered as a campaign platform.

- The Myanmar Press Council should also carry out the second action by hosting forums, consultation workshops, and debates with journalists from all over the nation to ensure that they have an in-depth comprehension of the code of ethics by debating it among themselves.

World views: The third layer

- International media development organizations should provide adequate funding and technical supports to the Myanmar Press Council in order to perform its functions as a media self-regulatory system.

- It is essential for Myanmar to sign and ratify international treaties that uphold and protect freedom of expression. These treaties include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the (first) Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination. By signing and ratifying these treaties, Myanmar demonstrates its commitment to promoting and safeguarding the fundamental right to freedom of expression in line with global standards.

- Article 354 of the Constitution of 2008 should be amended to strengthen protections for freedom of expression and the right to information. These guarantees should not permit ordinary laws to restrict these rights, but instead should impose clear conditions on any laws that do so.

- For media professional associations to effectively promote the rights of media workers and offer them support both in Yangon and across the nation, media development organizations should continue to support them.

Myth and Metaphor:

The fourth layer: The effectiveness of media policy and the future of press freedom in Myanmar will be greatly influenced by this most fundamental layer of reality, myth, and metaphor. The problems associated with press freedom and the effectiveness of media policies or laws in Myanmar cannot be resolved solely by enforcing or amending the law and holding forums and workshops on media ethics. The most important thing that needs to be reiterated is changing the narrative that is deeply embedded in the unconscious of the ruling government and the military personnel. To be achieved this

- Both the ruling government and the military should endeavour to grasp the significance of press freedom and recognize the crucial role that media plays within a democratic country

- The government and organizations focused on media development should keep supporting Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in their efforts to monitor media, run programs to enhance media literacy, and conduct research. Additionally, media literacy should be included as part of formal education in schools and universities

Bibliography

- Article19. (2014). Myanmar News Media Law. Article 19 .

- Athan. (2020). Analysis on Freedom of Expression Situation in Four Years Under the Current Regime . Athan .

- CPJ. (2014). www.cpj.org. Hentet fra https://cpj.org/data/imprisoned/2022/?status=Imprisoned&cc_fips%5B%5D=BM&start_year=2014&end_year=2022&group_by=location

- CPJ. (2016). www.cpj.org. Hentet fra www.cpj.org: https://cpj.org/data/imprisoned/2022/?status=Imprisoned&cc_fips%5B%5D=BM&start_year=2016&end_year=2022&group_by=location

- Devi, K. S. (2014). Myanmar under the Military Rule 1962-1988.

- Hulin, A. (2014 ). Statutory media self-regulation: beneficial or detrimental for media freedom? Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies.

- IMS. (Jan 2023). www.mediasupport.org. Hentet fra www.mediaupport.org : https://www.mediasupport.org/blogpost/myanmar-15-years-of-media-development-from-democratic-reforms-to-the-military-coup-and-beyond/

- Law, M. (2014 ). Burma Library . Hentet fra https://www.burmalibrary.org/docs17/2014-Media_Law-en.pdf

- Myanmar, 2. C. (2008). https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Myanmar_2008.pdf?lang=en. Hentet fra https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Myanmar_2008.pdf?lang=en

- NEWS, C. (23. April 2019 ). www.cbsnews.com . Hentet fra https://www.cbsnews.com/news/myanmar-reuters-journalists-wa-lone-kyaw-soe-oo-appeal-rejected-rohingya-crisis/

- PeMyint, D. (26. March 2016). Incoming Info Minister Pe Myint: ‘I Will Ensure Press Freedom’. (H. N. Zaw, Interviewer)

- PeMyint, D. (May 2016). Pe Myint: ‘A government needs to inform the people’. (N. H. Lynn, Interviewer)

- Suriyanto, S. (2018). The Function of the Press Council in Supporting Legal Protection for Journalists to Actualise the Press Freedom. Journal of Politics and Law .

- UNESCO. (2016 ). Assessment of Media Development in Myanmar . UNESCO.

- Wade, F. (2015). Burma’s Militarized Ministries. Foreign Policy .